Carbon emissions from Amazon wildfires could ‘counteract’ deforestation decline

Daisy Dunne

02.13.18Daisy Dunne

13.02.2018 | 4:00pmThe loss of carbon from wildfires fuelled by drought could “counteract” efforts to cut deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, research suggests.

A new study finds that, while rates of deforestation have sharply fallen in the Amazon over the past decade, the number of wildfires affecting the region has remained stubbornly high – particularly in drought years.

Emissions from wildfires totalled more than 1bn tonnes of CO2 from 2003-2015, the lead author tells Carbon Brief, and climate change, along with forest fragmentation, could cause a further increase in the number of forest fires in the coming decades.

The author adds that, if current efforts to curb deforestation are reversed, the combination of forest fires and deforestation could cause carbon loss from the Amazon to “escalate to proportions never experienced before”.

Three billion trees

The Amazon rainforest is the largest rainforest in the world, spanning an area that is 25 times the size of the UK.

The forest’s three billion trees absorb CO2 from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and then use it to build new leaves, shoots and roots. As they grow, these trees account for a quarter of the CO2 absorbed by the land each year.

The new study, published in Nature Communications, explores how this enormous carbon store is being affected by both deforestation and drought-driven wildfires.

The clearing of trees during deforestation causes previously locked-up carbon to be released back into the atmosphere.

The study finds that, despite remaining a major driver of forest carbon loss, rates of deforestation in the Amazon have fallen by 76% between 2003 and 2015. This reflects efforts by the Brazilian government to curb both legal and illegal deforestation, the study notes.

However, the amount of carbon loss from drought-driven wildfires has remained high, says lead author Dr Luiz Aragão, leader of the tropical ecosystems and environmental sciences group (TREES) at the National Institute for Space Research in Brazil. He tells Carbon Brief:

“This is the first time that we could clearly demonstrate how much widely-spread forest fires during recent droughts influence Amazonian carbon emissions. During these droughts, forest fires can overtake emissions from deforestation.”

Fanning the flames

![]()

Although wildfires occur regularly in the Amazon, fire incidence is at its highest in drought years.

“Drought years” happen on average every five years in the Amazon and are typically a result of changes to wind and weather patterns brought about by warming in the Atlantic Ocean during events of the climate phenomenon El Niño.

Although droughts have been a natural part of the year-to-year variations in the Amazon’s climate, both the frequency and severity of droughts in the rainforest have been increasing over the last decade because of climate change, Aragão says:

“These natural swings can be intensified by global warming. Another catalyst of this Atlantic oceanic warming is the declining Northern Hemisphere aerosol production.”

Previous research (pdf) shows that aerosols influence cloud formation in the rainforest and, therefore, the amount of regional rainfall.

Wildfires are usually sparked by humans clearing land, either for small-scale farming or major deforestation, Aragão says. During drought years, these small fires can quickly spread to large areas of the rainforest.

A lack of rainfall during drought years causes large sections of the lush canopy to dry out and die. These dry, dead leaves can then act as tinder, allowing small fires to spread, says Aragão:

“These forests would not burn naturally. Most of the fires that happen during droughts are human-driven. When the climate is drier, fires that are set for land management are more likely to leak into surrounding forests.”

As large areas of forest burn, huge stores of previously stored carbon are released into the atmosphere. The amount of carbon loss is greatest when fires “leak into” previously pristine forest, which may have been storing carbon for decades or even centuries, Aragão adds.

Assessing the damage

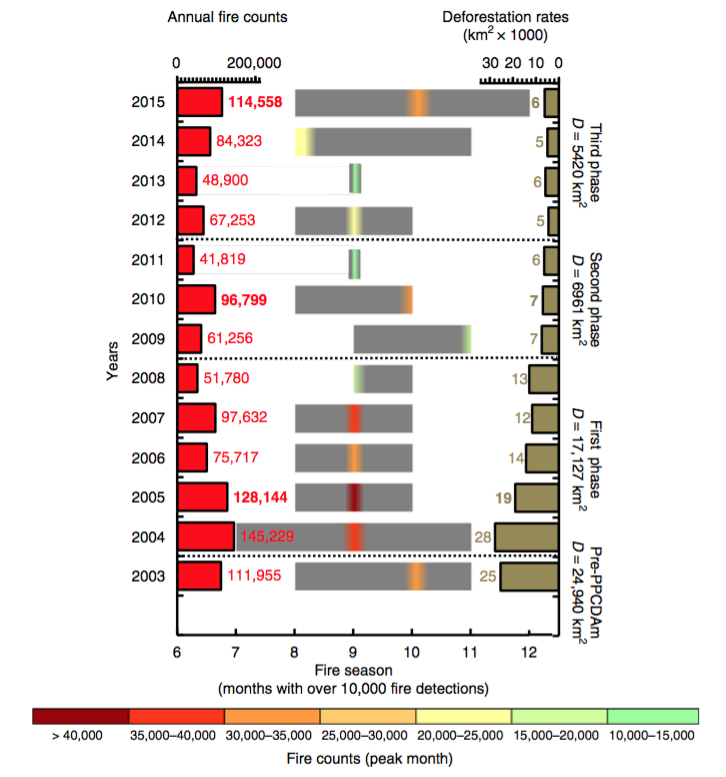

The researchers used satellite data to record the number and regional spread wildfires in the Amazon from 2003-15. The figure below shows the annual fire counts of each year of the study (red bars and numbers), with bold text signifying drought years (2005, 2010 and 2015). The numbers on the x-axis correspond to the fire season months from June (month 6) to December (month 12).

The length of the grey bars corresponds to the sum of all months with more than 10,000 fires. The colour within the grey bar shows the number of fire counts during the year’s “peak month”, with dark red showing a count of more than 40,000 and green showing a count of 10,000 to 15,000.

The chart also displays annual deforestation rates in the Amazon (khaki bars), which were derived from the Brazilian government.

The chart shows how the number of forest fires tends to spike in drought years. For example, during the 2015 drought, fire incidence was 36% higher compared to the average for the previous 12 years, the study finds.

Annual absolute fire counts (red bars) and deforestation rates (khaki bars) in the Amazon from 2003-15. Number of fires during drought years (2005, 2010, 2015) are shown in bold. The length of the grey bars corresponds to the sum of all months with more than 10,000 fires. The colour within the grey bar shows the number of fire counts during the year’s “peak month”, with dark red showing a count of more than 40,000 and green showing a count of 10,000 to 15,000. Source: Aragão (2018)

The results show that, while deforestation rates are decreasing, forest fire counts have not seen a similar decline.

This suggests that the role that deforestation plays in sparking forest fires is diminishing over time, says Aragão:

“Before we used to observe that fires in Amazonia were strongly related to deforestation. Now this relationship is weak. We think that there are few explanations, but a strong one is that because the Amazon is more fragmented, there are more edges between the deforested land and forests. This increases the chances of fires from open lands to propagate into forests.”

The effect of fragmentation could be magnified by future climate change, which is expected to bring more extreme droughts to the Amazon, he says:

“We expect that drought intensity and frequency will increase towards the end of the century. So, with more droughts it is very likely that fire incidence will also increase if no policy actions are taken to curb ignition sources.”

The researchers also used satellite data to record the total amount of CO2 released as a result of deforestation and wildfires over the study period.

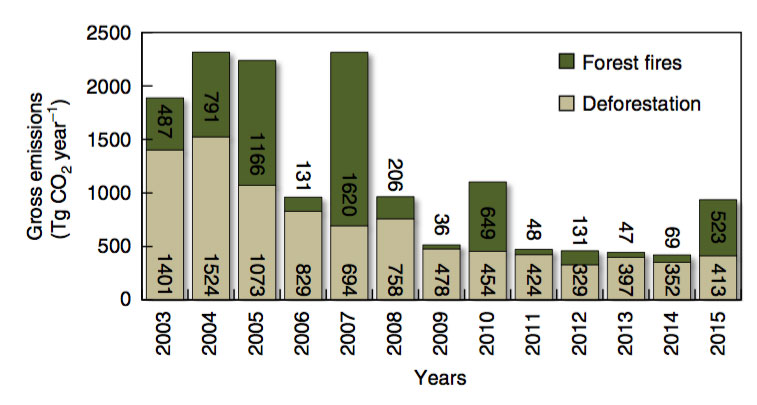

The results are shown on the chart below, which shows annual CO2 emissions in teragrams (one teragram is equal to 1m tonnes of CO2) for forest fires (dark green) and deforestation (light green).

Over the course of the study period, emissions from wildfires in drought years alone totalled more than 1bn tonnes, Aragão says. The release of CO2 during forest fires could increase further as the climate warms, he adds.

Annual CO2 emissions in teragrams (1m tonnes) of forest fires (dark green) and deforestation (light green) in the Amazon from 2003 to 2015. Source: Aragão (2018)

‘Compelling’ results

The “comprehensive” study raises concerns over the growing threat of wildfires in the Amazon, says Prof Guido van der Werf from Vrije University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. Van der Werf was part of a team that developed the Global Fire Emissions Database. He tells Carbon Brief:

“What is particularly compelling to me is the observed decoupling of fire and deforestation; they used to go hand in hand as fire was the cheapest tool in the deforestation process, but in recent years fires are observed more outside the deforestation regions, especially during drought years.

“Controlling these forest fires may be more difficult than controlling deforestation as it only takes one simple ignition to burn down a large area and many fires occur in secondary forests which may be less well monitored.”

The research uses a “sound methodology” but relies on statistics from the Brazilian government, which research suggests could be overstating recent deforestation reductions, says Dr Richard Birdsey, a senior scientist specialising in quantifying forest carbon budgets from the Woods Hole Research Centre, who also wasn’t involved in the research. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Some studies question the official statistics of deforestation in Brazil, suggesting that the reduction over previous decades may be overestimated. If deforestation is higher than the estimate used in this paper, then the relative effect of drought-induced fire would not be as large as stated here, and the decoupling of fire incidence from deforestation rates would not be as significant.”

Another factor not considered in the study is that forests tend to recover more quickly from wildfires than deforestation, he adds:

“Fires create young forests that will rather quickly recover significant amounts of lost biomass and usually have higher productivity compared with old-growth for several decades. Thus, considering the effects of fires over decades is an important consideration not addressed in this paper.”

Further carbon loss as a result of drought-driven wildfires could “counteract” efforts to curb deforestation in the Amazon, says Aragão. And, if efforts to stop deforestation are unsuccessful, the scale of carbon loss from the Amazon could reach “unprecedented” levels, he says:

“The main worry is that if deforestation increases, in combination with the increase fragmentation, increase in drought probability [caused by climate change] and the use of fires by humans, carbon emissions could escalate to proportions never experienced before.”

Aragão. L. E. O. C., et al. (2018) 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions, http://nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02771-y

-

Carbon emissions from Amazon wildfires could ‘counteract’ deforestation decline