Carbon capture and storage: Can the UK hit climate goals without killing off heavy industry?

Simon Evans

03.27.15Simon Evans

27.03.2015 | 10:00amThe UK should develop carbon capture and storage (CCS) clusters incorporating industrial sites as well as power plants, says the thinktank Green Alliance.

This would increase the amount of carbon captured nine-fold while cutting costs per tonne by two thirds, but it won’t happen without new financial incentives, says the 25 March report. Meanwhile new government roadmaps show heavy industry needs CCS to make significant emissions reductions.

The Green Alliance report is the latest in a long line to highlight the pressing need for CCS to cut carbon cost-effectively, while noting a long history of false starts and proposing a fresh approach to energising the sector.

Carbon Brief takes a look at why industrial CCS is considered essential to decarbonise sectors such as steel and cement, and why meeting UK carbon targets will cost more without it.

The case for industrial CCS

The attraction of CCS, and the reason it is opposed by some, is that it seems to offer the chance to keep burning fossil fuels while reducing emissions.

In December, David Cameron told MPs that CCS was “absolutely crucial if we are going to decarbonise effectively”. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says avoiding dangerous warming will cost twice as much without CCS.

UK decarbonisation would also be about twice as expensive without CCS, says a 17 March report from the Energy Technologies Institute (ETI).

However, research published in January shows CCS doesn’t actually make much difference to the total amount of fossil fuel that can be burnt, within a budget that gives a likely chance of limiting warming to less than two degrees above pre-industrial temperatures.

This adds to arguments that CCS shouldn’t be used to decarbonise coal- and gas-fired power stations on a large scale, since other low-carbon electricity sources are available. It’s a different story for heavy industry, however, where CCS is one of the few ways to radically cut carbon in line with UK and EU targets to reduce emissions by 80% or more by 2050.

The new Green Alliance report says CCS is “the only currently feasible technology” to cut emissions of many energy intensive industries, yet the UK’s current approach focuses only on cutting the cost of power sector CCS.

Meanwhile, Dustin Benton, the report’s author, explains that hundreds of millions are being paid every year to compensate these same industries for the cost of carbon prices. This protects them from overseas competitors that aren’t paying for carbon, but removes the incentive to cut emissions.

Benton tells Carbon Brief:

“Either you sort out industrial CCS, or you pay these industries forever to offset carbon costs. We think it makes sense to pay industry to help it decarbonise, rather than keeping going with compensation.”

Perhaps more importantly, it might be difficult for the UK to meet its 2050 carbon targets without help from industry. Sarah Tennison, low carbon economy manager for Tees Valley Unlimited, a partnership of local councils and businesses, says industry produces a third of UK emissions.

Tennison says:

“If we don’t find a way to finance industrial CCS, we’ll miss our carbon targets.”

Decarbonising heavy industry

Surely, there are other ways to cut industrial emissions without CCS? Richard Warren, senior energy and environment advisor for manufacturing industry group EEF, tells Carbon Brief:

“For some sectors like steel, chemicals, cement and refineries, you’re not going to get the kind of carbon reduction you want without CCS.”

A series of low-carbon industry roadmaps published by the government on 25 March appear to back Warren’s argument. They show how far different industrial sectors will be able to decarbonise by 2050 compared to 2012 levels, both with and without CCS.

The iron and steel roadmap says emissions could be cut by up to 60% – 14 million tonnes – with CCS providing half of this. The oil-refining roadmap says emissions can be cut by up to 70%. It says CCS is the only technology capable of providing the necessary “step change” in emissions, again accounting for more than half of the potential five million tonnes of emissions savings.

It’s a similar story from the cement roadmap, which finds savings of up to 62% – four million tonnes – are possible. It says industry carbon targets can’t be met without CCS and that CCS would account for nearly two-thirds of the technical savings potential. It adds that industry doubts there any other significant new emissions-cutting options on the horizon.

Finally, the chemical-industry roadmap finds emissions could be cut by 88% in 2050. CCS would account for about a quarter of the 15 million tonne reduction. Cumulatively, these four industrial sectors could shave 38 million tonnes off UK emissions by 2050 – around 9% of the 2014 total – of which around two-fifths is expected to come from CCS.

Total UK emissions must fall to 156 million tonnes in 2050 to meet its legally-binding climate goal. The roughly 15 million tonnes that industrial CCS in these four sectors alone could save is, therefore, highly significant.

Financing industrial CCS

The problem is there’s currently no policy in place to encourage industrial CCS, according to the ETI. Today’s carbon prices are far too low to warrant the high and uncertain costs of investing in carbon capture equipment: the industry roadmaps all refer to this as a major barrier.

Warren tells Carbon Brief this is a “massive policy gap”, and no-one appears to have yet found a solution. The Green Alliance report and others argue for financial incentives for industrial CCS, without suggesting what they should look like.

The government has given Tees Valley Unlimited £1 million to try to work out the feasibility of an industrial CCS cluster. Tennison is leading Teesside Collective, a group of industries aiming to create the conditions for a local CCS networl. She says the projects are working with French bank Societe General to come up with proposals for possible financial incentives schemes. This work should be finished in June.

The government is also supporting two power sector CCS demonstration projects: the White Rose scheme in Yorkshire and the Peterhead scheme in Scotland. Green Alliance says these should be expanded into clusters, drawing in nearby industrial sources (map, below).

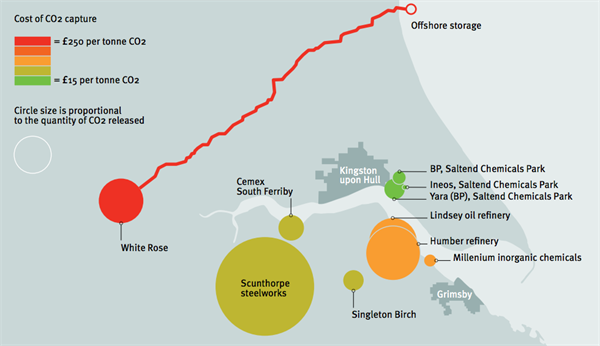

Proposed CCS cluster around the River Humber in Yorkshire. The size of the circles relates to the carbon emissions at each site while the colour indicates the estimated cost of capture, in pounds per tonne of carbon dioxide. Source: Green Alliance, Decarbonising British Industry.

Mervyn Wright, CCS design manager for National Grid, tells Carbon Brief it is no accident the White Rose CCS demonstration will include an oversized pipe system. The Peterhead scheme will use an existing pipe, but this is also oversized, Wright says.

Luke Wright, chief executive of the Carbon Capture and Storage Association, tells Carbon Brief the White Rose and Peterhead schemes could be the start of two industrial and power CCS clusters, even if they’re not officially described that way.

The cost of a Humber CCS cluster would be about £20 billion, Green Alliance suggests. This is four times more than the estimated £5 billion cost of the White Rose project, but would increase the amount of carbon dioxide captured from 1.5 million tonnes a year to 13 million tonnes a year.

Later this year, the power sector CCS schemes are due to sign “contracts for difference”, setting guaranteed prices for the electricity they generate. These would be similar to the deals being signed with wind and solar farms. This type of support wouldn’t be suitable for industrial CCS schemes, however, as many of them do not generate electricity.

Benton says one option to encourage industrial CCS clusters would be for government to remove carbon price compensation from those industries able to access a shared carbon transport and storage network developed with government support.

Conclusion

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) says it has “repeatedly” called for a CCS strategy covering industrial emissions in the 2020s. Last year, it said the industry roadmaps should set key milestones for CCS and describe the policies that would be needed to meet them.

Last August, the government said CCS was likely to be key to decarbonising industry. Its industry roadmaps agree, but they don’t set out how to make industrial CCS happen.

Warren tells Carbon Brief that needs to change:

“Further work on the roadmaps is essential. Without it they’re just another consultancy report that ends up gathering dust on the shelf.”

In principle, the CCC says UK carbon targets can be met without CCS. But if the UK wants to keep its remaining heavy industry at the same time, it is likely to need industrial CCS.

Main image: Oil refinery at night.

Update 30/3 - We added a reference to Teesside Collective.

-

Carbon capture and storage: Can the UK hit climate goals without killing off heavy industry?