Robin Webster

23.04.2014 | 1:30pmIncreasing energy demand is set to put pressure on the world’s water resources over the coming decades, according to a number of new expert studies. Even if the world shifts away from fossil fuels and toward cleaner power supplies, growing demand could help put water supplies under severe strain by the middle of the century.

From cooling down power plants and extracting, transporting and processing fuels to growing crops used as biofuels, energy production relies on water. Altogether, the sector accounts for 15 per cent of water withdrawals around the world, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Only agriculture is more water-hungry.

Yet demand is going up – just as growing populations and climate change put the world water supplies under even more pressure. Working out where water supplies for energy will come from in future is one of the “great challenges of our generation,” the World Resources Institute says.

Changing threats to water supplies

Water resources are already stretched. Groundwater extraction has tripled in the last 50 years in response to rising demand. Some underwater stores are now reaching “critically low levels”, according to the latest edition of the UN World Water Development Report, released in March.

The pressure’s likely to intensify. Agriculture already accounts for 70 per cent of freshwater use around the world, and it’s going to need at least another fifth again by the middle of the century, the UN says.

That’s not all. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s review of the future impacts of climate change, rising temperatures are going to increase the struggle for freshwater resources over the next few decades – exacerbating competition for water “among agriculture, ecosystems, settlements, industry and energy production” in already vulnerable regions.

Water demand from the energy sector

Into this mix, we have to add the energy sector’s need for water. Some 580 billion cubic metres of freshwater are withdrawn for generating energy every year – a scale of use the IEA calls “tremendous”.

The vast majority of this water use is for cooling down fossil fuel power plants. Coal, natural gas and oil – which together account for 80 per cent of global energy generation – create vast quantities of waste heat when burnt. The water is needed to carry the heat away and keep the power stations functioning.

Water also generates energy directly in hydroelectric power stations, which provide about 15 per cent of the world’s electricity.

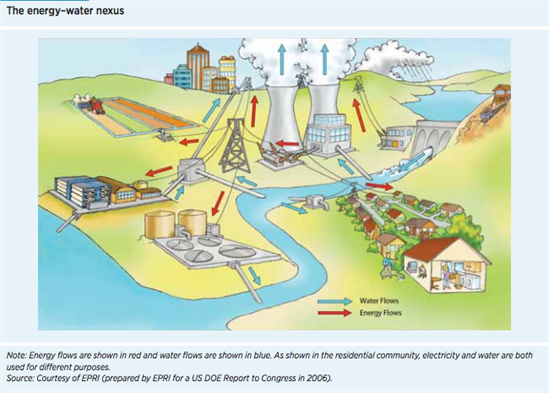

Energy and water are “highly interconnected”, the UN says – people use energy for water and water for energy. In wealthier countries, significant amounts of energy is used to clean water supplies up and transport water to populations.

The diagram below illustrates some of these relationships:

Source: United Nations world water report, March 2014

Water use and water stress

World primary energy demand will increase by 36 per cent between 2008 and 2035, the UN projects.

The vast majority of this increase is likely to take place in regions that are already under water stress. Poorer countries outside the OECD are expected will account for 93 per cent of the increase over the next thirty years, with China accounting for 36 per cent of it, according to its report. These regions are more likely to be already suffering from water limitations.

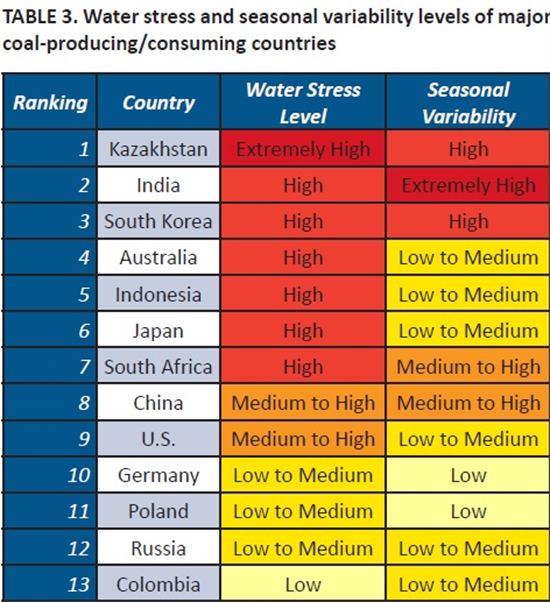

In a recent article, the World Resources Institute (WRI) mapped the world’s top coal producing and consuming countries against countries suffering from water limitations. As the table below shows, more than half of them already face high or extremely high levels of water stress:

Source: Identifying the global coal industry’s water risks, World Resources Institute, April 2014.

Regional disparities matter too. China alone accounts for more than half of planet’s coal consumption – and it has plans to expand. As of July 2012, the Chinese government had another 363 coal-fired power plants planned – an almost 75 per cent increase on its current levels, the WRI says. Half of these are in areas already suffering from high or extremely high levels of water stress.

New energy technologies

Plans to generate energy in new ways aren’t necessarily going to help matters. Extracting so-called unconventional sources of energy like shale gas and tight oil tends to use more water than conventional sources, the UN says, because water is injected at high pressure into rock.

Attempts to reduce emissions could also increase the energy sector’s need for water. Carbon capture and storage plants – which capture emissions from fossil fuels and store them underground – use about 25 per cent more water than conventional power plants, according to University of Sydney research. That’s because water is needed both to cool the solvents used to capture emissions and in the conventional power generation process.

Expanding the amount of power the world gets from bioenergy – crops, plants or trees – will also increase water demand. Crops need water in order to grow and to be converted into fuel – making the whole process highly water intensive.

More water consumption

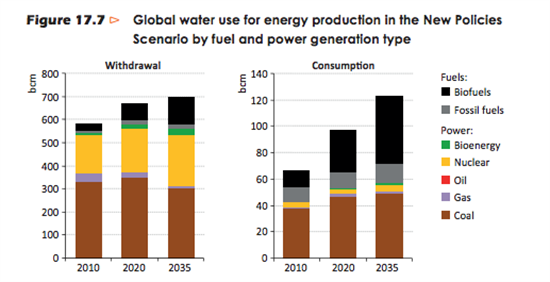

In assessing water use, it’s important to distinguish between water withdrawal and water consumption. Withdrawal refers to taking water from a source and then returning it later. Meanwhile, consumption happens when water evaporates or is incorporated into other products – so it doesn’t return to its source.

At the moment, the energy sector tends to withdraw water – to cool power stations, for example – and then return it later. Only about 10 per cent of water used for energy generation is actually consumed, the IEA says.

But in future, this could change, as we use more energy crops and shift toward more efficient power plants with advanced cooling systems that consume water. Water withdrawals by the energy sector could increase by about 20 per cent over the next 20 years, the IEA suggests – while water consumption could go up by a more dramatic 85 per cent:

Source: International Energy Agency, March 2012

The future

There is a bright side, however. Water requirements from other renewable technologies like wind and solar power are “negligible”, the IEA says. This makes them well-suited to a water- and carbon-constrained world.

In future, limitations on water supply could well affect where developers chose to locate new power stations – and even affect the extent to which new technologies like bioenergy and shale gas can develop.

Governments need to invest “heavily” in research and development into more water-efficient technologies, support the use of reclaimed water for irrigation and develop regional water plans that consider electricity needs, the UN report says. In China, the government is already planning to limit coal expansion in response to water availability.

The IEA expects the energy sector to become increasingly water-vulnerable. But it suggests the impacts are “manageable” with better technologies, more reliance on renewables, and intelligent power station siting. In its vision of the future world energy system, it assumes that water constraints can be overcome.

Politicians and energy company bosses involved in shaping the world’s future energy systems will probably have to hope that this assumption is correct.