Budget 2021: Key climate and energy announcements

Multiple Authors

03.03.21The UK’s chancellor Rishi Sunak has delivered his second budget under the cloud of the coronavirus pandemic and his last ahead of the country hosting the COP26 UN climate talks.

In contrast to last year’s offering, Sunak’s speech and budget “red book” gave much less space to climate change and the UK’s net-zero target. The red book uses the word “climate” only nine times, against 31 last year, with seven appearances for “net-zero”, down from 17.

Nevertheless, climate change and net-zero do feature relatively prominently in the red book, which says: “The budget lays the foundations for a strong recovery and greener economy, levelling up the country and spreading prosperity across every part of the UK.”

Significantly, net-zero has been made part of the government’s overall “economic policy objective”. This puts it into the remit for the Bank of England’s monetary and financial policy committees. The budget also launched a new National Infrastructure Bank, which has £22bn of “financial capacity” as well as tackling climate change as one of two core objectives.

Other climate-related announcements were relatively few and far between. As expected, the budget froze fuel duty for the 11th year. Sunak also pledged the release of at least £15bn of “green gilts” this financial year. These are government bonds dedicated to supporting net-zero.

Below, Carbon Brief summarises all the key climate and energy announcements from today’s budget:

- Green finance

- Infrastructure

- Fuel duty

- Innovation

- Green homes grant

- Carbon pricing

- Road building

- Media reaction

Green finance

In what is being seen as one of the most significant parts of this year’s budget for climate action, Sunak announced that the UK’s net-zero goal will be added to the remit of the Bank of England, having become part of the government’s overall “economic policy objective”.

In one of two letters to the Bank of England’s governor Andrew Bailey, Sunak writes:

“I am today updating the MPC’s [the bank’s monetary policy committee] remit to reflect the government’s economic strategy for achieving strong, sustainable and balanced growth that is also environmentally sustainable and consistent with the transition to a net-zero economy.”

In the second letter, regarding the bank’s financial policy committee, Sunak uses much stronger language to describe the challenge of climate change than he did in his budget speech. He writes:

“As the world recovers from the pandemic, we also face a tipping point for our climate. The shift to a world where we are at net-zero will mean systemic changes across all parts of our economy. This includes delivering a financial system which supports and enables the transition to an environmentally sustainable net-zero economy by expanding the supply of green finance, and that is resilient to the physical and transition risks that climate change presents.”

The implications of these changes in remit are not immediately clear, but one potential effect could be to force the bank to consider climate change risks as part of its emergency coronavirus response. Last year, the bank ignored such risks when buying corporate debt as part of efforts to prop up the economy, leading to criticism from green groups.

Update 4/3: The Financial Times reports that the Bank of England has already responded to the chancellor’s budget by saying that it would adjust its approach to buying corporate debt, to take climate risks into account. Bloomberg also reports the news, saying the bank “will seek to start greening its corporate bond-buying program from the end of the year”.

The budget promises that the government will issue its first “sovereign green bond – or green gilt” in summer 2021, a move it had already announced last November. At least £15bn in government debt will be specifically earmarked for supporting “green objectives”, with further details of how it can be spent coming in June.

In another move trailed before today’s budget, Sunak also announced a “green retail savings product” in summer 2021, which will “give all UK savers the opportunity to take part in the collective effort to tackle climate change”. The money raised will be spent according to the same rules as the government’s new green gilts.

Separately, the chancellor’s budget announces a “carbon markets working group”, which the red book says has the aim of “positioning the UK and the City of London as the leading global market for high quality voluntary carbon offsets”.

Infrastructure

The budget includes a variety of commitments to spending on infrastructure projects across the UK, as well what Sunak called the nation’s “first-ever” infrastructure bank.

In his speech, Sunak said the UK’s “future economy needs investment in green industries” and, to this end, he said the bank would be established in Leeds “to finance the green industrial revolution”.

He added that it would begin in the spring, with an initial provision of £12bn of money and the ability to guarantee up to another £10bn of debt, with the expectation that it would support at least £40bn of investment in infrastructure.

Update 4/3: According to the Daily Telegraph, the new bank “will offer loans and investments worth two-thirds less than EU predecessor”. The paper says the European Investment Bank lent an average of £5bn a year to projects in the UK, according to the Treasury’s independent Office for Budget Responsibility, which compared that figure to the expected £1.5bn a year from the new UK infrastructure bank.

While the chancellor described it as the UK’s “first ever” infrastructure bank, the nation launched a green infrastructure bank in 2012 before selling it off just five years later under Theresa May’s government.

The budget was accompanied by an additional document outlining the policy design of the new bank, laying out its main objectives to “support regional and local economic growth”, as well as help meet the net-zero emissions target. Describing the bank’s ability, it says:

“It can bolster the government’s lending to local government for large and complex projects and help to bring private and public sector stakeholders together to regenerate local areas and create new opportunities.”

According to the policy design document, the bank will have £22bn of “financial capacity” to deliver on its objectives, consisting of £12bn of equity and debt capital mentioned by the chancellor as well as the ability to issue £10bn of guarantees.

A further document released to accompany the budget, titled “Build back better – our plan for growth”, paints a positive image of the government’s plans for infrastructure.

It includes references to the government showing low-carbon leadership at the COP26 climate summit and the supposed “transformational opportunity” for infrastructure provided by Brexit.

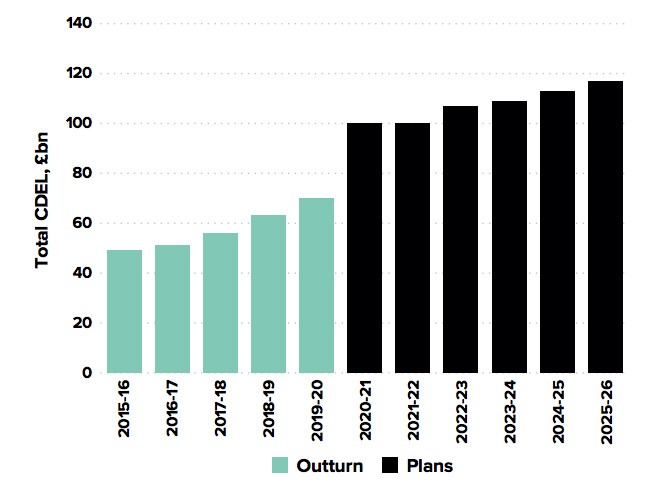

The report emphasises the need to “deliver infrastructure projects better, greener and faster”. It adds that the government is committed to ramping up capital spending, as the chart below shows.

It also references the large disparities across the UK in terms of contributions to the national economy, with London and the South East contributing around 24% and 14% of national output, respectively, while the North East and Northern Ireland contribute around 2.5% each.

The budget contains various chunks of money aimed at boosting infrastructure in some overlooked regions.

Teesside and Humberside were mentioned as the location for new port infrastructure to build “the next generation of offshore wind projects”. (Sunak mentioned “Teesside” four times in his speech.)

This support was previously mentioned as part of the £160m spending on manufacturing and ports infrastructure in the prime minister’s 10-point plan.

There was also an investment of £57m to support jobs and green growth in Scotland. This includes £27m for the “Aberdeen energy transition zone”, which aims to transition northeast Scotland into a hub for offshore wind and hydrogen, and £5m for a “global underwater hub” in Aberdeen to improve its subsea engineering capacity.

A “Holyhead hydrogen hub” in Anglesey will receive £4.8m to “pilot the creation of hydrogen using renewable energy and its use as a zero-emission fuel for heavy goods vehicles”, something the government says would create “high-skilled green jobs”.

There is also a mention of the £5.2bn flood and coastal defence programme for England from last year’s budget, which will start in April this year with schemes in Waltham Abbey, Sunderland, Preston, Warrington, Salisbury, Rotherham and Doncaster.

Fuel duty

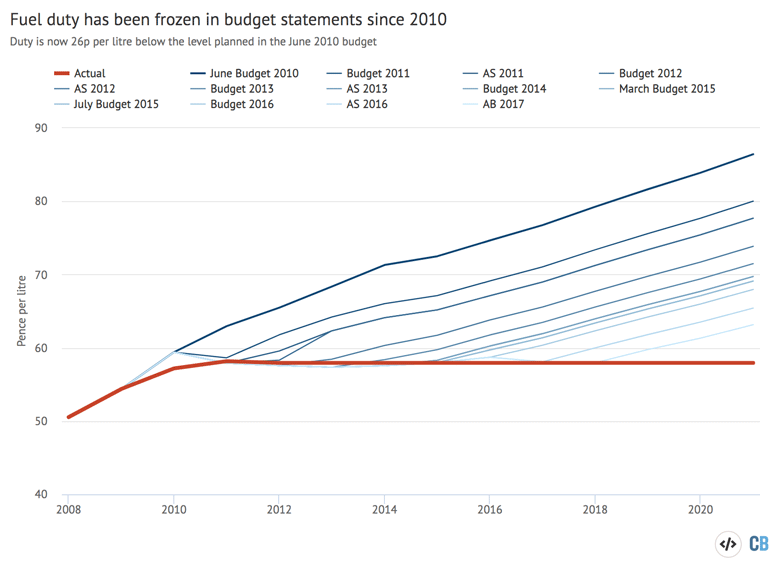

Sunak confirmed that fuel duty will remain frozen for yet another year. The tax, levied on sales of petrol and diesel, has remained at a rate of 58 pence per litre, plus VAT, since 2011.

Alongside the continued freeze, however, the Treasury’s budget “red book” signals potential rises in the future. It says: “Future fuel duty rates will be considered in the context of the UK’s commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.”

The latest freeze will cost the Treasury nearly £1bn a year in lost revenue, according to the government’s own policy costings, which take account of “an increase in [fuel] consumption in response to lower fuel price increases”.

Instead of rising with inflation, fuel duty has now been frozen for more than a decade, as the chart below shows. This is a large tax cut for motorists, with successive freezes adding up to more than £10bn a year and having cost the Treasury more than £100bn in total.

In an October 2019 report on the taxation of motoring, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said: “There is no case for the recurrent ritual…when planned inflation uprating of fuel duties has been repeatedly cancelled for one more year.”

In contrast to the real-terms cut in the price of driving, public transport fares have often gone up faster than inflation, creating an ever-increasing cost differential. Confirming the latest increase in rail fares of 1% above the rate of inflation, the government said in December that it “reflected the need to continue investing in modernising the [rail] network”.

According to the Zero Carbon Campaign, which is calling for “a proper price on carbon…more broadly across the UK economy”, there is widespread support among the British public for a carbon tax. It says there is much lower support for fuel duty increases, because of a perception they are an ineffective way to cut emissions.

Carbon Brief analysis published last year found that, overall, UK carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions were up to 5% higher than they would have been without a decade of fuel duty freezes.

The latest freeze was briefed to the media prior to the budget speech, with the Sun on Monday claiming “a major victory for the Sun’s legendary Keep It Down campaign”.

In his blog at the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, former government advisor Tim Lord writes that fuel duty raises around £30bn a year for the Treasury. He argues that while the cost of the fuel duty freeze is large, a bigger problem is the rise of electric vehicles: “[This] is going to eat into fuel duty revenues quickly and we have no plan for how to respond.”

Alongside the fuel-duty freeze, the budget also freezes the rate of vehicle excise duty (VED, often referred to as “road tax”) for heavy goods vehicles. However, the general rates of VED for cars, vans and motorbikes will rise with inflation, as will air passenger duty on flights.

In last year’s budget, Sunak set out stiff restrictions on the availability of reduced-duty “red diesel”, which is used on farms and construction sites. This year’s budget includes further details, following consultation, including slightly more generous ongoing exemptions.

Innovation

The budget contains a handful of smaller funds as part of the government’s “commitment to double spending on energy innovation”.

They are part of its £1bn net-zero innovation portfolio, outlined in the energy white paper, which previously only contained a competition to fund direct air capture and emissions removal technologies.

Three competitions to develop new technologies to help achieve net-zero emissions have now been added, specifically £20m to develop floating offshore wind projects, £68m for green energy storage systems and £4m to boost clean energy crops and forestry.

Separately, the government announced funding of up to £30m that will provide match-funding for the Global Centre for Rail Excellence in South Wales.

This money is intended to “support innovation in the UK’s rail industry, including the testing of cutting-edge, green technology”.

Green homes grant

A centrepiece of plans for climate-focused government spending over the past year has been the “green homes grant”, which allows people to apply for vouchers to cover the cost of home insulation or installing low-carbon heating.

The chancellor first announced the £2bn in grants for home-efficiency upgrades, as well as £1bn for improvements in public buildings, as part of his “green recovery” plans in July 2020, although his party’s election manifesto had previously promised £9.2bn for energy efficiency.

This was then given a boost in the prime minister’s 10-point plan published last November, when a further £1bn and an extra year was added to the existing scheme for home improvements.

However, at the same time, stories emerged of a scheme beset by difficulties, with companies going unpaid and customers waiting months to take advantage of the grants.

After much speculation, reports surfaced in February that the government did not intend to roll over most of the unspent grants to the next financial year, effectively withdrawing £1bn in funding and leaving just £320m for 2021 to 2022.

Just 6.3% of the £1.5bn set aside for households has been spent in 2020/21, according to the i newspaper. (The remaining £500m from the original £2bn is for local authorities to spend on low-income households.)

While the government attributed the lack of uptake to the public’s “understandable reluctance” to “welcome tradespeople into their homes” due to Covid-19, environmental organisations were quick to point the finger at government mishandling.

In a piece for BusinessGreen, Green MP Caroline Lucas wrote:

“In its inimitable style, this government has managed to make a complete mess of delivering the scheme. First it awarded the contract to an American company that seems to be thoroughly incompetent; then it strangled it in paperwork with conflicting and confusing information, and so many delays that householders simply give up.”

In guidance issued ahead of the budget, Environmental Audit Committee (EAC) chairman Philip Dunne said the grant scheme “must be overhauled and given a multi-year extension if it is to meet the government’s target of issuing 600,000 vouchers”.

As it stands, fewer than 23,000 vouchers have been issued despite more than 70,000 households applying for the scheme.

The EAC also advised that there should be VAT reductions on energy efficiency upgrades in homes, as well as on repair services and items that have been recycled.

Following the intense debate around the green home grants, there was speculation ahead of the budget about what it would say about their fate.

As it turned out, neither the chancellor himself nor the entire 107-page budget document made any mention of the grants. However, when contacted by the Financial Times, the Treasury confirmed that much of the original funding had indeed been withdrawn.

Carbon pricing

A Sun article in the run up to the budget quoted prime minister Boris Johnson saying he had no intention of introducing new “meat or carbon taxes” that would impact consumers.

Nevertheless, there has been a lot of conversation in the UK in recent months about different options for carbon pricing, particularly following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

While the Treasury reportedly would have preferred to implement a carbon tax to replace the EU emissions trading scheme (ETS), the government’s energy white paper eventually confirmed that the UK would have its own UK ETS instead.

Like the EU ETS, this system is meant to cover high-emitting actors, such as power plants, heavy industry and domestic airlines, which will be allocated credits to emit greenhouse gases that they can also purchase if they emit beyond set limits.

Although some details of the UK ETS have already been published, a lot of uncertainty still remains and the first auctions are not set to be held until 19 May.

There have been concerns that, without EU membership, there will not be enough participants in the UK system for it to function effectively and help cut emissions.

However, the government has so far been vague about any plans to link its system with those operating in other nations, stating in the white paper that the UK is “open to linking the UK ETS internationally…but no decision on our preferred linking partners has yet been made”. According to the budget text:

“The government is committed to carbon pricing as a tool to drive decarbonisation and intends to set out additional proposals for expanding the UK ETS over the course of 2021.”

However, it remains to be seen what “expanding” the scheme will entail.

The UK also has its own domestic carbon tax in the power sector which goes back to when it was part of the EU ETS, known as the carbon price support. This was originally brought in due to the low carbon price signal at the time under the EU’s system.

The new budget confirms that, as it did last year, the government has decided to freeze the carbon price support at £18 per tonne of CO2 in 2022-23.

Road building

Billed as the “largest ever investment in England’s motorways and major A roads”, a commitment to spending £27bn on roadbuilding over the next five years was a key component of last year’s budget.

It was also one that attracted criticism from environmental groups, who compared this significant sum to the relatively small amounts spent on green measures and questioned how it fits in with the government’s commitment to net-zero emissions.

The new budget does not mention the government’s road-building plans at all, although a document released to accompany it, titled “Build back better – our plan for growth”, references it several times.

It also emphasises the government’s focus on promoting “the importance of low-carbon infrastructure” and achieving its net-zero target, one of the “people’s priorities”.

Environmental consultancy Transport for Quality of Life found last year that emissions from the scheme would wipe out 80% of the emissions saving from electric cars up to 2032, although the Department for Transport dismissed this analysis as “wholly incorrect”.

However, a recent National Audit Office report concluded that, “while there has been an increase in the number of ultra-low emission cars and the required charging infrastructure, carbon emissions from cars have not reduced in line with government’s initial expectations.”

It attributed this, in part, to a rise in the sale of sports utility vehicles (SUVs) and also “increased road traffic and travel by car”. There is evidence that building new roads leads to a greater overall volume of traffic.

Meanwhile, the Guardian reported in February that the £27bn scheme had been “thrown into doubt after documents showed the transport secretary, Grant Shapps, overrode official advice to review the policy on environmental grounds”.

Media reaction

Much of the media coverage of the budget echoed the concerns of environmental organisations who described it as a “missed opportunity” to take decisive action on climate change.

An editorial in the Guardian said “the climate emergency was noticeable by its absence”, while an editorial in the Financial Times noted “there were few concrete measures to ensure that post-Brexit Britain will…achieve its target of net-zero carbon emissions”.

The budget “did little to bring down emissions or address the hard parts of climate policy,” according to Politico.

It also noted that the chancellor “took more than half an hour to get to the green section” of his budget speech “despite the tub thumping his government has done over net-zero, green recovery and hosting this year’s COP26 UN talks”.

BusinessGreen published a piece summarising the response from the “green economy”. Among those quoted is Philip Dunne, chair of the Environmental Audit Committee, who welcomed the National Infrastructure Bank and the expansion of the Bank of England’s remit, but added:

“The chancellor has today missed an opportunity to go further: reducing VAT for green sectors including energy efficiency upgrades, and investing more significantly in renewable and low-carbon energy.”

Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf wrote:

“A UK Infrastructure Bank with capital of £12bn will not amount to much. Where is the ambition for investment? Where is the plan for environmental policy? Where, for that matter, is the discussion of carbon pricing? After the massive response to the pandemic, the needed long-term vision for a country facing an uncertain future is absent.”

According to the Daily Telegraph, the new bank “will offer loans and investments worth two-thirds less than EU predecessor”.

The newspaper said the European Investment Bank lent an average of £5bn a year to projects in the UK, according to the Treasury’s independent Office for Budget Responsibility, which compared that figure to the expected £1.5bn a year from the new UK infrastructure bank.

Several publications, including the Daily Mail and the Daily Telegraph, also reported on the fuel duty freeze, with the former noting it “is likely to increase [in the future] to help the government meet climate change targets”.