Britain’s fish ‘n’ chip favourites could dwindle as North Sea warms

Robert McSweeney

04.13.15Robert McSweeney

13.04.2015 | 4:20pmThe likes of haddock, plaice and lemon sole could find the North Sea a less comfortable place to live as the world’s oceans warm up, according to a new study.

The findings suggest that some of our favourite fish species could become less common as they struggle to cope with warming conditions, the lead author tells Carbon Brief.

Close to our culinary hearts

The fishing industry in the North Sea is worth over $1 billion a year. Some of Britain’s best-loved fish are caught there, such as haddock and cod, which are among the top five most-consumed fish in the UK.

But the findings of a new study, published in Nature Climate Change, suggest that warmer waters will make the North Sea less suitable for many of our mealtime favourites. And they may not be able to migrate to other areas, the researchers say.

North sea temperatures have risen by 1.3C over the last 30 years and are predicted to rise by a further 1.8C over the next 50 years. The study estimates how these rising temperatures will affect some of the most abundant North Sea fish species.

The researchers looked at eight bottom-dwelling fish, known as ‘demersal’ species: dab, haddock, hake, lemon sole, ling, long rough dab, plaice, and saithe. Lead author, Louise Rutterford, from the University of Exeter, explains why to Carbon Brief:

“North Sea demersal fish species are the ones that we Brits most associate with the North Sea and they are close to our culinary hearts. There is also great data available from the UK and international trawl surveys.”

Abundance and distribution

Using 30 years of fisheries data from the North Sea and projections for climate change, the researchers developed models to estimate future abundance and distribution of the eight fish species by the middle of this century.

The models take into account factors such as sea temperatures at the surface and near the seabed, and salinity. They project future fish numbers and the latitudes and depths were the fish are most likely to be found.

Contrary to expectations, the study finds fish may not search out cooler, deeper waters or head north as the North Sea warms.

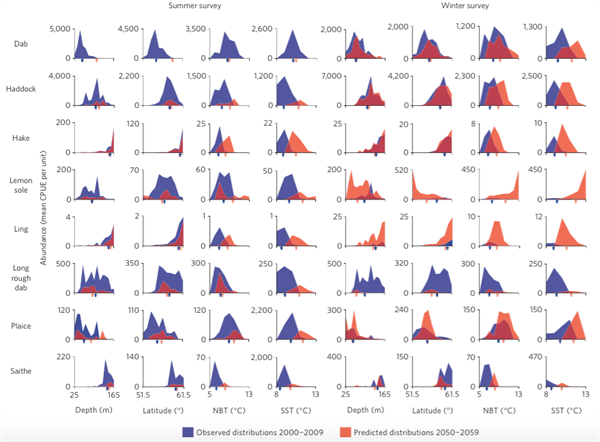

You can see this in the graphs below. They are arranged in a grid: each row showing a different fish species, and each column showing how fish distributions are expected to change in terms of latitude, temperature and depth. The results for fish abundance are shown in blue for present day and red for the middle of the century.

The results for lemon sole (fourth row down) in summer show lower fish abundance in future, but with their distribution staying much the same. Both near-bottom temperature (third column) and sea surface temperature (fourth column) show warmer conditions for future. However, the depth (first column) and latitude (second column) suggest the fish will be found in similar areas to the present day.

The results for dab (top row) show a large reduction in summer abundance. Dab tend to live in shallow waters in the southern North Sea, says Rutterford, which is expected to experience the warmest summer temperatures. These temperatures may be higher than they can tolerate, Rutterford says.

Observed and projected abundance of eight fish species in the North Sea, according to depth, latitude, near-bottom temperature (NBT) and sea surface temperature (SST). Blue areas show observed distributions (for 2000-2009) and red areas show projected (for 2050-2059), with corresponding arrows along the x-axis to show average distribution. Estimates shown for summer (left-hand set of graphs) and winter (right-hand). Source: Rutterford et al. (2015).

Reduced reproductive potential or survival

So why wouldn’t the fish move to cooler waters as temperatures rise? Previous research has shown that North Sea fish preferring cooler waters have shifted around five metres deeper during the 1980s. But the new study suggests there isn’t enough suitable habitat to go further, Rutterford says:

“We suspect that due to the general habitat and depth profile of the North Sea – deeper and rockier to the North – there are limits to further movement or distribution changes since habitat of suitable depth has already been exhausted.”

It’s not just temperature that’s important for fish habitat. The amount of light, type of seabed sediment, availability of food, preferred areas for spawning, and lack of predators all play a role. So it isn’t as simple as the fish moving to cooler waters.

But if fish aren’t able to move from their existing habitat, the high temperatures can affect how they grow, Dr Lisa Crozier, a research ecologist from the Northwest Fisheries Science Center at NOAA, who wasn’t involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“In some cases, fish that develop under cooler conditions grow better later in life than those that develop at higher temperatures. This can be an immediate effect – within one lifetime – or genetic change over many generations.”

Species can acclimatise to higher temperatures but it can take many decades or centuries, Crozier says. And even if they adapt, their numbers could still be affected:

“Even with acclimation or evolution, there will likely be reduced reproductive potential or survival as part of the process.”

Feeling the squeeze

So what are the implications for fish in the North Sea and on our chip shop menus? The results suggest some of the species we eat most will struggle to cope with warming conditions, Rutterford says:

“Our models predict that some cold water species may be squeezed out, with warmer water fish likely to take their place.”

Unless the fish can adapt to the warming, it’s likely that fish stocks will be affected, the paper concludes.

An earlier study, by some of the same authors, found that the warming seas around the UK have already seen a decline in haddock, cod and pollack as warmer water species, such as red mullet, have increased over the last 30 years.

The outcome won’t be the same for all fish species in all seas, Prof Ian Perry, a senior research scientist at the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the University of British Columbia, points out to Carbon Brief:

“Species that live fully up in the water column are not likely to be constrained by bottom depth and bottom habitat conditions in the manner demonstrated here for these bottom fishes.”

Nevertheless, we may see some of our traditional favourites being replaced by fish from the warmer climes of our southern European neighbours.

Rutterford, L.A. et al. (2015) Future fish distributions constrained by depth in warming seas, Nature Climate Change, doi:10.1038/nclimate2607