Brexit negotiations should treat energy as ‘special case’, says report

Jocelyn Timperley

05.10.17Jocelyn Timperley

10.05.2017 | 11:11amThere are strong practical reasons why the UK and EU should treat energy as a special case during Brexit negotiations, argues a new report.

The report, jointly authored by Chatham House, the University of Exeter and the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC), says finding common ground on energy during the Brexit negotiations would benefit both the UK and remaining EU27, while compromise may be relatively easier to achieve than for other areas.

Carbon Brief breaks down the policy areas the UK will have to address in the negotiations, from interconnectors and emissions trading to Euratom and energy funding, as well as the recommendations given on each of these areas in the report.

A special case?

Energy has been a low-profile area in the Brexit discussions so far, with February’s Brexit White Paper relatively vague on what the UK’s future energy relationship with the EU might look like.

The Chatham House report argues that there are strong reasons why both the UK and the remaining 27 EU member states (EU27) should treat energy – and especially electricity – as a special case.

Electricity provision is vital public service, essential for the economy to function, but the difficulty and expense to store it means a clear regulatory framework is needed to ensure real-time availability and system stability, the report says.

Meanwhile, the growing decarbonisation of the energy sector will increase the use of variable sources such as wind and solar photovoltaics, whose efficiency is enhanced by cross-border electricity trade.

Antony Froggatt, senior research fellow at Chatham House and co-author of the report, also points to the statements the government has made on protecting network industries, which would include energy. “In that way I think there’s recognition that there are certain sectors that we’ll have to make adjustments for,” he tells Carbon Brief.

He adds there are also mutual benefits if the UK remains fully integrated with the EU on energy, such as for the bilateral relationship which will need to be made with Ireland to maintain its Single Electricity Market (SEM), or the drive to support regional development of offshore grids.

Interconnectors

Interconnectors – pipes or wires that transfer energy across borders – are recognised as an important part of minimising the costs of low-carbon electricity, by allowing variable surplus electricity from renewables to flow to areas with a deficit at any given time.

The UK’s relatively isolated electricity market makes it especially reliant on interconnectors to mainland Europe. Its current proposals would see it treble its electricity interconnection by 2025, from 3 to 10 GW. Froggatt says:

“I think [interconnectors] are important because not only does the UK intend to increase the amount of electricity it’s getting from the continent, but they are also a physical manifestation of to some extent uncertainty in the market. If you’re going to operate these in the most efficient way – ie intraday trading – you will need to be sort of fully covered with a market.”

The report urges the UK to aim to remain “fully integrated” with European energy networks to ensure existing and future interconnectors are used as efficiently as possible – for economic, environmental and security-of-supply reasons.

However the UK will still move away from being a rule setter to some extent to being a ruletaker, says Froggatt – assuming it will be allowed to fully participate at all.

Euratom

The UK has confirmed it intends to leave Euratom, the 1957 treaty which established the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC) and governs the EU’s nuclear industry, including health and safety and non-proliferation.

This so called ‘Brexatom’ could have a major impact on the UK’s nuclear industry, impacting nuclear material safeguards, safety, supply, movement across borders and R&D among other things, the report says.

Achieving this exit within the two-year Brexit time frame will also be extremely difficult, as it will require the UK to establish a new framework agreement on nuclear safety and security to allow it to trade nuclear materials and comply with international norms.

However, much of this process will have to wait until at least after the initial Brexit negotiations. For example, a decision and deal will have to be made over whether Euratom or the International Atomic Energy Agency (IEAE) will oversee safeguards of the UK’s future uranium supply, before future deals with third party suppliers can be made. The government should also consider establishing new institutions responsible for ensuring that nuclear safety and health and safety standards are adhered to, the report says.

One key thing to note about Euratom is that, unlike for much of trade, there is no possibility to default to World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules as a default, as no such rules exist for this area

EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS)

The UK has not formally made any decision on whether it will remain part of the EU Emission Trading System (EU ETS), however it has ruled out accepting jurisdiction from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) – the ultimate jurisdiction for the EU ETS.

So while a deal could in theory be made for EU ETS legislation to continue to apply to the UK, this is not possible if the UK continues to rule out ECJ jurisdiction.

A second option, the Chatham House paper says, would be for the UK to establish its own emissions trading scheme, and seek agreement to link it to the EU ETS. However, while there are precedents in Norway and Switzerland, the process could be complex, making it unlikely to be completed before the UK leaves the EU.

The other way to maintain carbon pricing in some form outside of the ETS would be to build on the carbon floor price and introduce a carbon tax.

![]()

Neither Theresa May’s Brexit speech nor the government’s February white paper made any mention of the ETS.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has calculated the UK would have to increase its overall emissions target from 57 to 61% reduction from 1990 levels by 2030 if it left the EU ETS. This is because emissions from the power sector and large industrial emitters would start counting directly against the ‘gross’ UK carbon budget, rather than as ‘net’ emissions within the EU ETS. (For a more detailed explanation of carbon budget accounting, see this earlier Carbon Brief article).

The UK no longer being part of effort sharing in the EU ETS would also have implications for the remaining EU states in terms of their targets, says Froggatt. “So there may be some stronger argument for saying ‘let’s make a deal around this’.”

Meanwhile, as the UK makes a higher than average contribution for emissions cuts in sectors outside the EU ETS, the simplest option for the EU27 would be for the UK to remain part of the EU’s climate change accounting at least in the short term, the report says. This could be a way to exercise leverage over the EU27, such as to secure continued UK participation in the ETS, it adds.

A new energy union?

The UK climate policies have evolved over years alongside the EU’s, including multiple packages over the past 20 years harmonise the EU’s internal energy market (IEM).

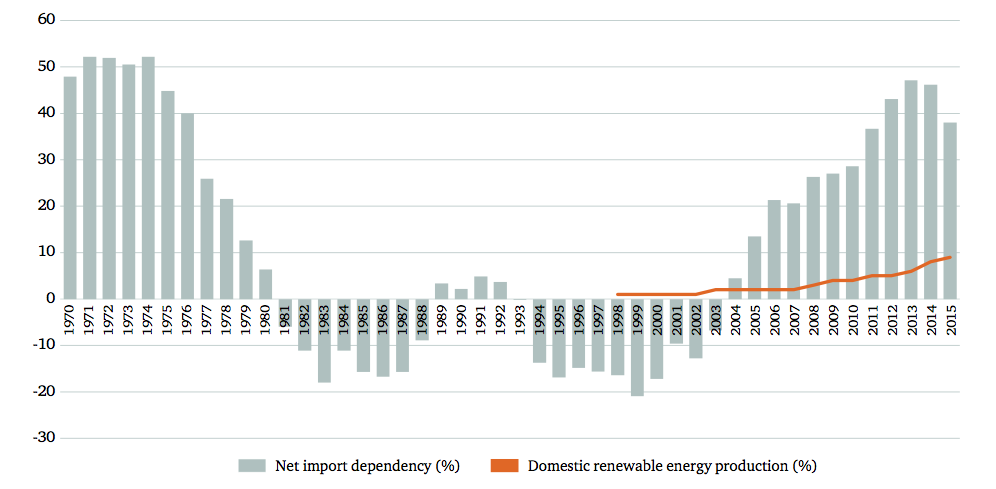

Aside from policy, the UK is also deeply intertwined with the rest of Europe in physical energy terms. Some 38% of UK energy came from imports in 2015, with most of this supplied by the EU or Norway.

The UK’s net energy import dependency. Source: Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics (2016); chart by Chatham House.

Energy cooperation is crucial for both the EU and the UK, by enhancing their geopolitical security, responding to growing climate threats, and creating a competitive pan-European energy market, the report says. The UK’s continued integration in the IEM will therefore be of future importance for both parties.

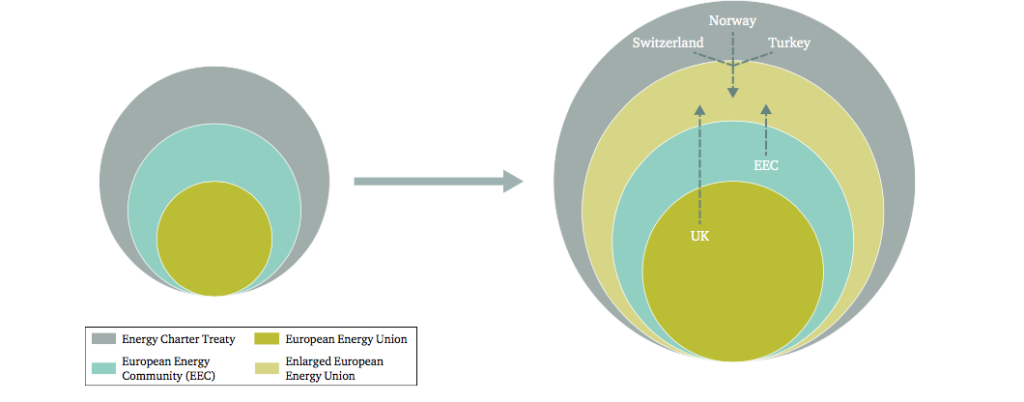

There are several ways these links could be maintained. The EU already has several energy relationships with neighbours, with different levels of integration into the IEM which the UK could look to for a blueprint.

These include strong relationships with Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein via the European Economic Area (EEA) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA); a bilateral agreements with Switzerland (which is in EFTA but not the EEA); and the Energy Community, which links EU members states with nine non-EU neighbours including Albania and Ukraine who are expected to abide by IEM rules.

The EU also has over 50 preferential trade agreements with countries and organisations around the world, the report points out, while a customs agreement with Turkey allows some energy trade to take place with neighbouring EU member states, and has led to Turkey fitting in with many of the IEM rules to facilitate trade despite not being required to do so.

One things that could be done, the report argues, would be to revamp all this by creating a new multilateral energy grouping for member states and neighbouring countries, which it dubs the ‘Enlarged European Energy Union’ (EEEU). As well as using a common framework to help the close integration of neighbouring countries’ energy markets into the IEM, this would also agree to common goals for environmental protection and allow neighbouring countries such as Norway and the UK to be more closely involved with EU policymaking in this field.

A pan-European framework for energy cooperation – dubbed the ‘Enlarged European Energy Union’ – proposed by Chatham House. Chart by Chatham House.

It’s worth noting, however, that it remains unclear what discussions can take place about future partnerships or sector specific dialogues in parallel with the initial Brexit negotiations.

The report argues a transitional energy arrangement may be needed in case negotiations are not completed before new European Commission is appointed in June 2019. Questions over the role of the UK’s devolved administrations in future UK energy policy complicate this picture further.

Funding

A well used argument throughout the Leave campaign was that the UK would be better off financially after Brexit since the UK is a net contributor to the EU.

It’s worth noting, however that the UK’s energy sector benefits financially in several ways by being part of the EU, with important funding given to infrastructure, development, research and development (R&D), as well as to meeting climate change mitigation goals.

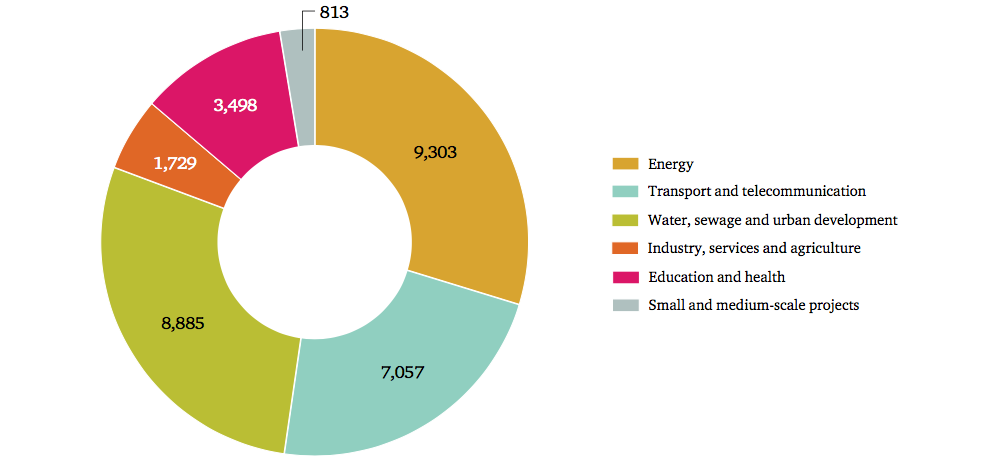

For example, the UK receives 15% of EU R&D funding, a higher proportion than its overall financial contribution to the EU budget of 12%. Overall, EU grants and European Investment Bank (EIB) loans account for around £2.5bn of the UK’s energy-related infrastructure, climate change mitigation, and R&D funding per year.

This leaves a decision to be made by the government as to how this funding will be replaced.

The UK government has committed to maintaining levels of EU funding, at least in the short term, but the report argues more action than has been announced so far will be needed to replace the loss of EU funds and loans.

Froggatt says the key question is how far up the priority list energy will be for funds currently being paid to the EU. “It’s not automatically going to be subdivided back into the ways that we have been sending money to Europe, and so in some ways energy will be competing with farming and all of those other areas which currently are recipients of cash, or recipients of funding from the EU. But there will also be competition against other areas in which there is seen to be a strong domestic need, [such as the] NHS [and] education, etc.”

Meanwhile, it is not yet clear what impact Brexit will have on funds from the European Investment Bank (EIB). According to the report, the perception is “firming up among financiers” that access to EIB or EU funds during Article 50 negotiations cannot be assumed, raising the risk of financing gaps emerging.

EIB lending to the UK by sector, 2012–16 (€ million). Source: EIB; chart by Chatham House.

The EIB is the most important individual source of finance for UK infrastructure, and while the UK provides more funding to the EIB than it receives back, there is again no guarantee as to where this money will be directed once it is in domestic hands.

The president of the EIB meanwhile has suggested that keeping the UK as a shareholder post-Brexit should not be ruled out.

-

Brexit negotiations should treat energy as ‘special case’, says report

-

Treating energy as a special case in Brexit negotiations will benefit both UK and EU27, report argues