Bonn climate talks: Key outcomes from the June 2023 UN climate conference

Multiple Authors

06.16.23Multiple Authors

16.06.2023 | 4:15pmClimate negotiations kicked off once again this month in the German city of Bonn, as diplomats from around the world searched for common ground before the next big UN summit COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Developing countries had scored a “win” six months earlier at COP27 in Egypt when they secured a “loss-and-damage fund” for people struck by climate disasters.

At Bonn, delegates were tasked with laying the groundwork ahead of a “global stocktake” that will see nations assessing their progress towards climate goals. Their schedules were also packed with the various workshops and “dialogues” that underpin the UN climate system.

Yet tensions ran high as negotiators failed to agree even on the starting agenda for the talks until the day before the two-week session was due to close.

The situation prompted veteran diplomat Nabeel Munir, who was overseeing the talks, to compare those present to “a class of primary school”. He pointed out that 33 million people in his native Pakistan were affected by floods last year and urged delegates to “wake up”.

Yet the squabbles at Bonn’s World Conference Centre were steeped in history. Many related to long-standing grievances over the provision of money that developing countries say they need in order to cut their emissions.

Here, Carbon Brief runs through the key issues and outcomes from the talks in Bonn.

- ‘Unavoidable’ change

- Mitigation

- Climate finance

- Global stocktake (GST)

- Loss and damage

- Adaptation

- Just transition

- Article 6

- Road to COP28

‘Unavoidable’ change

The Bonn negotiations got underway amid continued concerns about the COP28 presidency. The United Arab Emirates COP president-designate Sultan Al Jaber has faced significant criticism due to his role as chief executive of the country’s national oil company ADNOC.

Last month, more than 130 European and US lawmakers published an open letter calling for Al Jaber to be removed from the role, according to numerous publications, arguing that having the head of one of the world’s largest oil and gas companies as COP president risked undermining the negotiations.

The COP28 chief briefly attended the 58th sessions of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC’s) Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) and Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) – referred to as SB58, in Bonn.

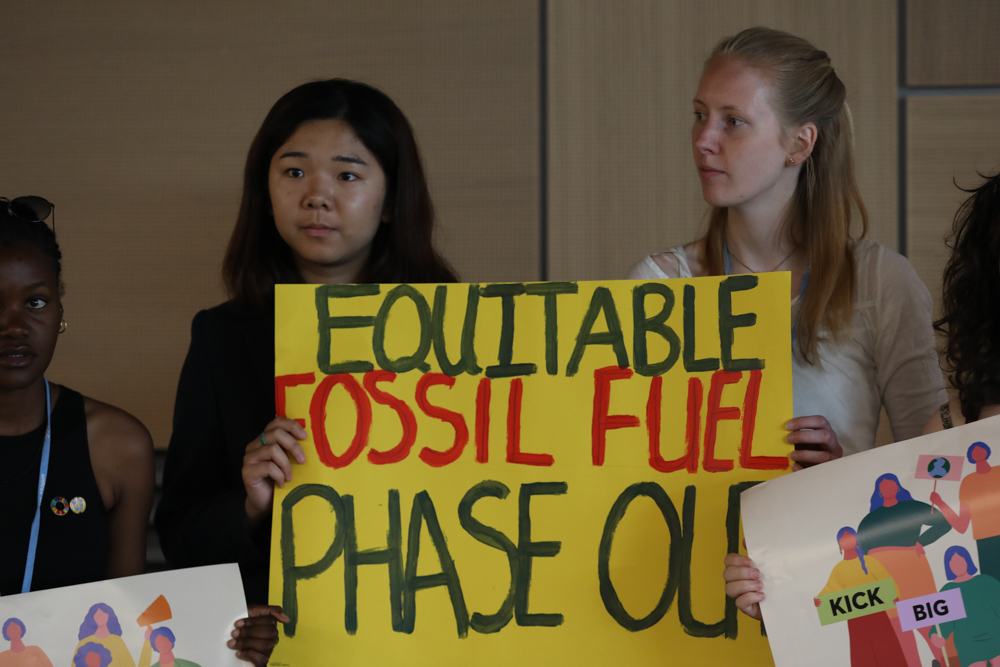

During a brief speech, he did admit that a fossil fuel phasedown is now “inevitable”, the first time he has explicitly acknowledged the idea – though he stopped short of mentioning a timeline. In addition, he told youth groups that there was the potential for COP28 to discuss a target to triple renewable energy by 2030.

This follows the failure of the final COP27 text to include a call for a phase down of fossil fuels, as had been proposed by India, the EU, the US and others. That language in itself was considered too limited by many, who pushed for a commitment to a total fossil fuel phaseout.

Andreas Sieber, associate director of global policy at 350.org, said in a statement:

“COP28 president and oil CEO Al Jaber says at the UN climate talks that fossil fuel reduction is unavoidable. It’s time for action, talk alone is cheap. Al Jaber must step up by presenting a solid plan and selecting a pair of ministers to facilitate and elevate discussion on energy transition. COP28 cannot conclude without committing to a complete and equitable fossil fuel phase-out and setting ambitious renewable energy targets.”

While Al Jaber’s shift in language is notable, it falls short of the calls from many for a total fossil fuel phaseout. Protest chants on this point were common from youth groups throughout Bonn, as were comments from NGOs and beyond.

Many pointed to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report highlighting the need for rapid cuts in fossil fuel use in order to limit warming to 1.5C, when discussion of an energy transition or a just transition arose.

However, it remains a topic that divides parties.

At the closing plenary session, which Carbon Brief attended, St Kitts and Nevis on behalf of AOSIS (the Alliance of Small Island States), noted that it had been at 10 informal consultations on the IPCC’s sixth assessment report (AR6) during the two weeks.

They highlighted their concern at the level of compromise they felt was made around how the report was included in the final agenda from Bonn, which should be a “no-brainer”.

The sentiment was echoed by the EU, Environmental Integrity Group (EIG, which includes Switzerland, South Korea and Mexico), Canada, Norway, US, New Zealand, Australia, UK and Senegal, all of which shared the concern that the importance of the IPCC AR6 is not reflected in the outcome from Bonn, despite it being “the most comprehensive and robust assessment of climate change”, as the US put it.

There remain many questions around what COP28 will look like and how successful it can be, given both the leadership and wider geopolitical tensions – not least Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which led delegates to walk out during Russia’s opening remarks at Bonn.

Delegates walk out of the opening plenary of the Bonn #SB58 climate meeting as Russia calls Ukraine 'puppet of the West' while responding to intervention by the US condeming the war in Ukraine. Several minutes of back & forth statements on the war by the US, the UK & Russia. pic.twitter.com/dGLEepcOEc

— Dharini (@dharinipart) June 5, 2023

On 5 June, as the Bonn climate change conference got underway, disagreement over fossil fuel phaseout hung heavy in the air. This was a major reason why talks quickly faltered, as an agenda dispute that would dominate the event emerged.

Mitigation

One of the core areas of contention at Bonn was the inclusion of the Sharm el-Sheikh Mitigation Ambition and Implementation Work Programme (MWP) within the agenda.

The MWP, which aims to “urgently scale up mitigation ambition and implementation in this critical decade”, was established at COP26 in November 2021, recognising that countries’ collective efforts are well short of what would be needed to meet global climate goals.

At COP27 in November 2022, parties agreed that the MWP should begin immediately.

Parties, observers and other non-party stakeholders were also invited to submit their views on opportunities, best practices, actionable solutions, challenges and barriers relevant to mitigation ahead of 1 March 2023.

Following this, Sweden, on behalf of the EU, requested the MWP be formally added to the agenda at Bonn.

The work programme for 2023 was set to focus on a just energy transition, Amr Osama Abdel-Aziz (Egypt) and Lola Vallejo (France) confirmed head of the first “global dialogue and investment-focused event”, which took place in Bonn over 3-5 June 2023, ahead of the conference.

This dialogue saw discussions on renewables, energy efficiency and electricity grids, but, crucially, not the fossil fuel phaseout, and as an extension a just transition.

It is within this context that negotiators went into the Bonn climate change conference. As Tom Evans, policy advisor on climate diplomacy and geopolitics at E3G, explained during a briefing on the final day of the talks:

“[With] six months to go to a COP, at halftime, it feels like those pushing for fossil fuels phase out are one-nil down. I think there are lots of questions as to how we turn this round on the road to COP.”

The opening plenary session at Bonn was delayed while consultations with parties were undertaken with regards to two agenda items – the MWP as proposed by the EU and the National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) as proposed by G77 and China.

When SBSTA chair Harry Vreuls (Netherlands) and SBI chair Nabeel Munir (Pakistan) convened the opening plenaries of both bodies together, they announced that, despite extensive consultations, there was no consensus on the agenda. Work was, therefore, launched on the basis of the supplementary provisional agenda, while further consultation was undertaken on these elements.

Two days later, on 7 June, Bolivia, on behalf of the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC), submitted a request to add an additional agenda item on “urgently scaling up financial support from developed country Parties in line with Article 4.5 to enable implementation for developing countries in this critical decade”.

While mitigation is widely agreed to be vitally important, the economic toll of actions to mitigate the impact of climate change could be a significant burden to many developing countries for whom financing is already a challenge. Given limited resources, paying for mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage – as well as schools, hospitals and other key elements of infrastructure – simply is not a reality for many countries.

As such, Bolivia on behalf of the LMDCs – later publicly supported by others such as the Arab Group, and Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) – argued they could not accept the inclusion of the MWP on the agenda, without the new financial support item.

This created a deadlock, with many concerned the agenda would not be adopted at all, with all of the work undertaken over the two weeks at risk of not being counted.

Following further discussions – bringing it up to 11 hours of agenda consultations, according to SBI chair Munir – a second plenary was called on 12 June.

At the meeting, attended by Carbon Brief, an amendment to the relevant items on the work programme on just-transition pathways within the agenda were accepted. However, the debate over the inclusion of the MWP remained unresolved, with the chairs again bringing the plenary to a close without the agenda being adopted.

Bolivia continued to highlight the need for upscaling finance for developing countries, arguing a dedicated space was needed to discuss the “means of implementation” and, thus, the MWP should not be adopted without the addition of a finance track.

However, the EU, together with the Environment Integrity Group (EIG), the US, Norway, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and Japan pushed back. They argued that finance was already part of a number of different agenda items and would be within MWP.

In the plenary, Diego Pacheco Balanza, the LMDC chair, called the comments “concerning and worrisome” to listen to, suggesting that developed countries were trying to shift their responsibilities for providing finance.

In what was a common reference throughout the conference, he pointed to the failure of developed countries to meet their $100bn a year by 2020 goal, set out at COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009.

This failure has seemingly damaged the trust between those from the global south and the global north. Ambassador Wael Aboulmagd, special representative of the COP27 president, told Carbon Brief it was “regrettable” that over the years, the “symbolic trust-generating objective” had not been achieved.

Ultimately, the plenary was called to a close with the agenda still yet to be accepted, while concern amongst parties and observers grew.

Both the SBI and SBSTA finally adopted their agendas on the conference’s penultimate evening, to the relief of many. SBSTA chair Harry Vreuls stated:

“The SBI chair and I are pleased to report today that the continued consultations have enabled parties to reach an agreement on the agendas. We now feel that the time is right to adopt these agendas and would like to sincerely thank parties who met, consulted with us and with each other, in order to agree on the continuous issues in the spirit of compromise and flexibility.”

Ultimately, the MWP and the proposed item on financial support were dropped from the agenda, with an informal note set to be issued by the SB chairs capturing the work carried out on the MWP in Bonn. Vreuls additionally noted that this did not set a precedent for future work.

There will be another dialogue on the MWP later this year, ahead of COP28 and, while the topic of that dialogue has yet to be confirmed, the question around the phase out of fossil fuels – and the economics of such within a just transition – is likely to hang heavy.

Climate finance

Most of the negotiations at the conference did not focus directly on finance. Yet, as is always the case at UN climate talks, money permeated nearly every aspect of the event.

A new post-2025 climate-finance goal to provide developing countries with the funds to cut their emissions and increase their resilience to climate hazards is in the works.

This “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) was mandated by the Paris Agreement and must be agreed by COP29 in 2024. However, these discussions remained highly technical in Bonn.

In the meantime, the missed $100bn target loomed large over proceedings. Developed countries have still not met this 2020 goal for financing developing countries and, while they expect to hit it this year, their failure has contributed to serious mistrust among parties.

(According to analysis by Oxfam, once loans and non-climate specific finance are stripped away from the total that developed nations have provided, they were actually less than one-quarter of the way to their goal in 2020. Developing countries would generally prefer to receive grant-based finance that does not push them further into debt.)

There was a sense among many delegates in Bonn that the lack of sufficient climate finance was holding up proceedings. Indeed, the agenda dispute over the LMDCs’ request for more finance discussions almost upended the entire conference. (See: Mitigation.)

This mood was referenced by Tina Stege, climate envoy from the Marshall Islands, who told Carbon Brief at a press conference:

“The gaps are clear…We need to address all of the gaps and finance is the key to unlocking and getting the change we need.”

She referenced an “entire change of the financial architecture”, adding “that’s essentially what needs to be contemplated”. This ties in with a dawning realisation that addressing climate change globally will cost trillions, not billions, of dollars.

The idea of comprehensive reforms to the world’s financial systems is already gathering momentum, with Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley’s Bridgetown Agenda including a substantial package of proposals.

These have, in turn, fuelled discussions around World Bank reform and a summit, convened by French president Emmanual Macron in Paris next week, on a “new global financing pact” between the global north and the global south.

There are hopes that such actions, beyond the confines of the UN climate process, could help to close the gaps mentioned by Stege between developing countries’ needs and capacities.

Yet not everyone is happy with this kind of framing. Meena Raman, a senior legal adviser with Third World Network, told a press conference in the closing days of the event:

“The new mantra that is here is Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement…And why do [developed countries] say that this is the most important aspect for them? Because they want to shift away from the obligations that are mentioned in Article 9 of the Paris Agreement.”

Article 2.1c refers to countries “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low

greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”. Article 9, rather than focusing broadly on finance flows in general, says developed countries “shall” provide money to developing countries.

Article 2.1c is not inherently problematic. It essentially requires all public and private finance to be aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

But climate-justice groups and many developing countries see the focus on Article 2.1c as an attempt by developed countries to escape their climate finance obligations.

They say the US, the EU and their allies want to make developing countries rely on private-sector investment and loans, while broadening the list of climate-finance donors so relatively wealthy developing nations, such as China and the Gulf states, also have to contribute.

Moreover, campaigners said it was hypocritical of the US and others to push this framing while still subsidising fossil fuels at home.

“There is a fundamental disconnect from a country that claims a mantle of climate leadership,” Alex Rafalowicz, director of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, told reporters at a press briefing.

Speaking at the beginning of week two in Bonn, US negotiator Trigg Talley called for both more focus on private finance and the expansion of the donor base. “If finance is urgent then it would make sense to consider all such sources,” he said.

Yet there are also reasons why developing countries that are highly reliant on fossil fuels, such as Saudi Arabia, might want to keep climate-finance conversations fixed on developed countries’ obligations. Tom Evans, a policy adviser at E3G, tells Carbon Brief:

“They can use that as a shield. They are more concerned that the more we talk about [2.1c] financial flows, we’re literally talking about ending fossil-fuel investment.”

Indeed, Saudi Arabia and other nations with big fossil-fuel industries, such as China, were among those vocally supporting the call from the LMDCs for “urgently scaling up financial support from developed country Parties in line with Article 4.5”.

(This paragraph of the Paris Agreement says “support shall be provided to developing country parties” to help them cut emissions. The US argued that Article 4.5 does not explicitly require developed countries to provide this support.)

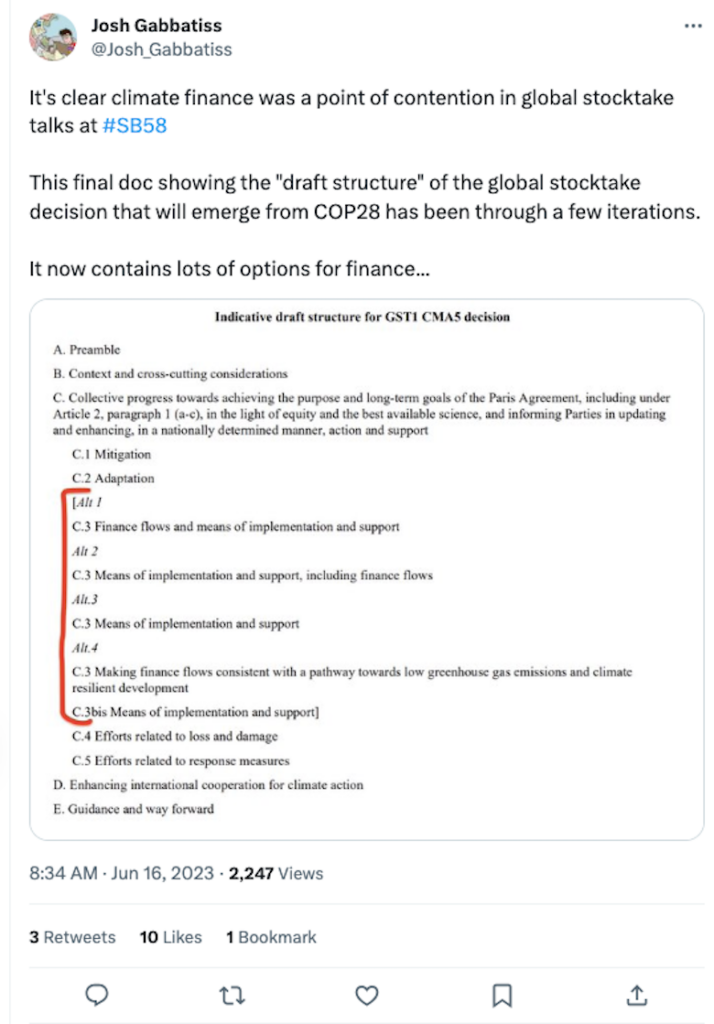

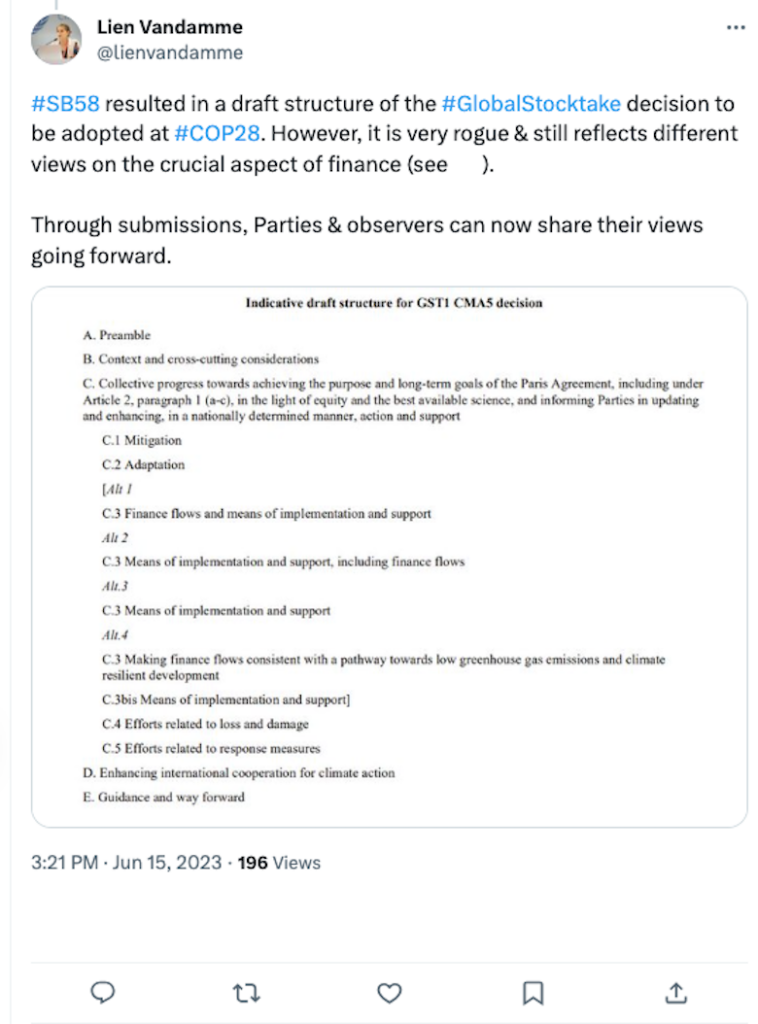

These discussions also seeped into negotiations on the global stocktake. The draft document for how the stocktake would be structured was revised a few times, with the section on climate finance showing the most significant alterations. (See: Global stocktake.)

Again, this reflected disputes around the prominence of Article 2.1c between developed countries and certain developing countries. The final version included four different options for finance, including one that did not mention “finance flows” at all.

As for the post-2025 climate-finance target, the Bonn talks included the sixth technical expert dialogue on the climate finance “NCQG”.

Its themes were the “quantum” – that is, the amount of money – and “mobilisation and provision of financial sources”. The target will not be set until 2024, but a key issue is that, unlike the $100bn target, it is supposed to be based on a detailed assessment of how much money developing countries need to meet their climate targets.

David Chama Kaluba, a climate finance negotiator for the African Group from Zambia, told Carbon Brief following the first meeting on this subject that there had been “substantial progress”, adding that “I think we are now answering the real questions”:

“There are no numbers being discussed yet…We don’t want to come up with a number abruptly, which is not informed by any technical aspects.”

Others expressed concerns that developed countries did not want the NCQG to reflect the true needs of developing countries. Senegalese LDC chair Madeleine Diouf Sarr said in a statement after Bonn concluded that “some seem to want to disconnect developing country needs – which are in the trillions – from the quantified goal”.

Sara Shaw, climate justice and energy international programme coordinator at Friends of the Earth International, summarised these feelings at a press event, telling Carbon Brief:

“We’re struggling even to get millions…When we’re actually looking at needing trillions. It feels like a bit of a parallel universe sometimes, in terms of what our demands are and what is actually on the table.”

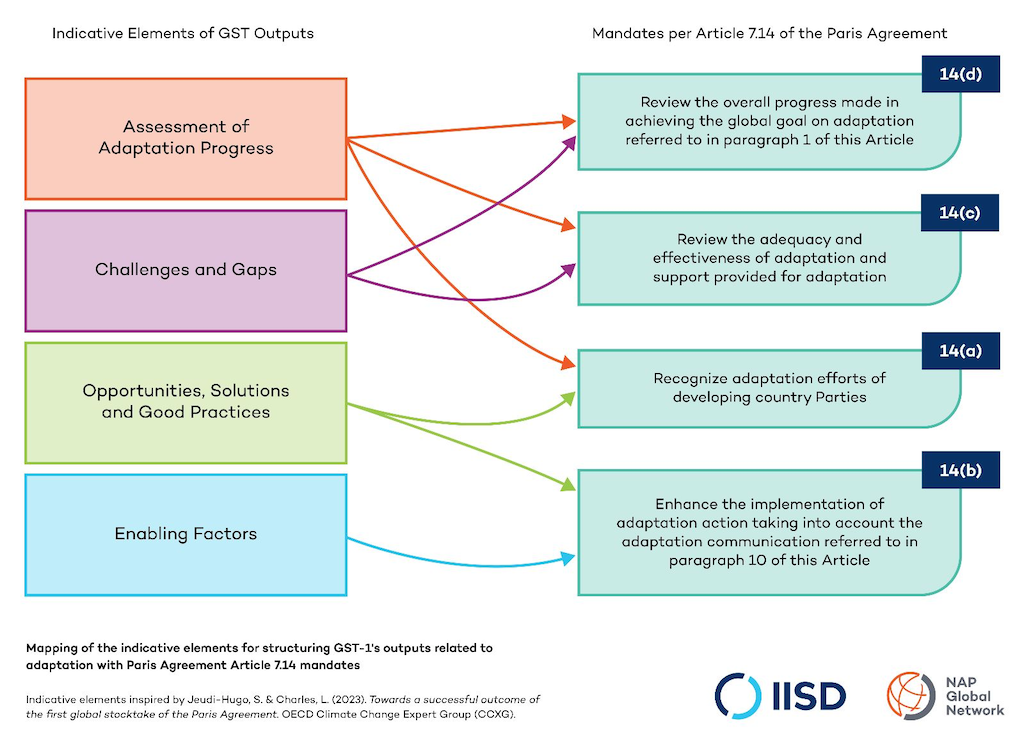

Global stocktake (GST)

At COP28 the first global stocktake (GST) will take place, providing a look at where the world is, where it needs to go and how to get there, if it is to address climate change.

This is a central element of the Paris Agreement, designed to inform the next round of national climate pledges so countries can “ratchet up” ambition as necessary to limit warming.

It is well understood that nations are not on track to meet their targets and that these targets themselves are not enough to limit warming to 1.5C. As E3G’s Tom Evans stated at a briefing at Bonn:

“We know we’re way off track. We know we haven’t done enough to limit warming to 1.5C, that we’re on track for that and we know we’re unprepared for climate disasters. But, in many ways, the big prize of COP28 is an ambitious response to that state of affairs and one that could actually course correct and get us back on track or even on even beyond track.”

The first “dialogue” for the GST took place at the Bonn talks in June 2022, the second at COP27 in Egypt in November 2022 and the third – and final before COP28 – took place at Bonn this June.

A draft framework for the GST was published during the second week in Bonn, containing five key area:

- Preamble;

- Context and cross-cutting considerations;

- Collective progress towards achieving the purpose and long-term goals of the Paris Agreement, in the light of equity and the best available science, and informing parties in updating and enhancing, in a nationally determined manner, action and support;

- Enhancing international cooperation;

- Guidance and way forward.

Of these, the most contentious was the third section (labelled “C” in the image below), focused on collective purpose and long-term goals of the Paris Agreement, which included subsections on mitigation, adaptation, finance flows and means of implementation and support, efforts related to loss and damage, and efforts related to response measures.

Throughout the negotiations – and in line with others discussions on elements, such as adaptation, mitigation and loss and damage – finance flows, the means of implementation and the historical responsibility of developed countries became the focus of many disagreements.

For example, as reported by the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Saudi Arabia, China and others suggested the text should be changed to place implementation ahead of finance flows, or that the reference to finance flows be removed.

The US rejected this, suggesting implementation and support should sit as a subsection under finance flows, but New Zealand, Canada and Australia disagreed, arguing financial flows are a broader issue than means of implementation.

The co-chairs of this agenda item, Alison Campbell (UK) and Joseph Teo (Singapore), attempted to find compromise. However, when delegates reconvened for an evening session on the penultimate day on Bonn, it was agreed that this subsection would include several options, rather than an agreed upon wording.

Instead, several options for the subsection on finance flows and means of implementation were included in the final draft.

While this allowed the GST dialogues to come to a close, during the closing plenary, parties including Australia pointed to the other significant point of contention – the historical responsibility of developed countries.

In a statement, Australia said:

“We recognise that under Paris developed countries take the lead by undertaking economy-wide absolute emissions reduction targets. We developed our economies during a time when there was no alternative to fossil-fuel based energy sources and when there was little scientific understanding or multilateral consensus on the harm represented by greenhouse gas emissions and the need to address climate change as an international issue.”

This followed developing countries, led by the G77 and China, underlining historical emissions within the technical dialogues and calling for an equitable share of the “carbon space”. The US pushed back against this, branding the comments “unacceptable”.

Ultimately, this disagreement did not derail the discussions, leaving COP28 still set to be the “GST COP”, as many have dubbed it.

Within his closing speech, UN Climate Change executive secretary Simon Stiell said:

“Pledges by parties and their implementation are far from enough…So, the response to the stocktake will determine our success – the success of COP28 and, far more importantly, success in stabilising our climate.”

There will be a summary report on the third meeting of the technical dialogue on the GST by 15 August 2023. This will be followed by a factual synthesis report produced by 8 September 2023, which will bring together all the assessments that have formed part of the third dialogue.

Loss and damage

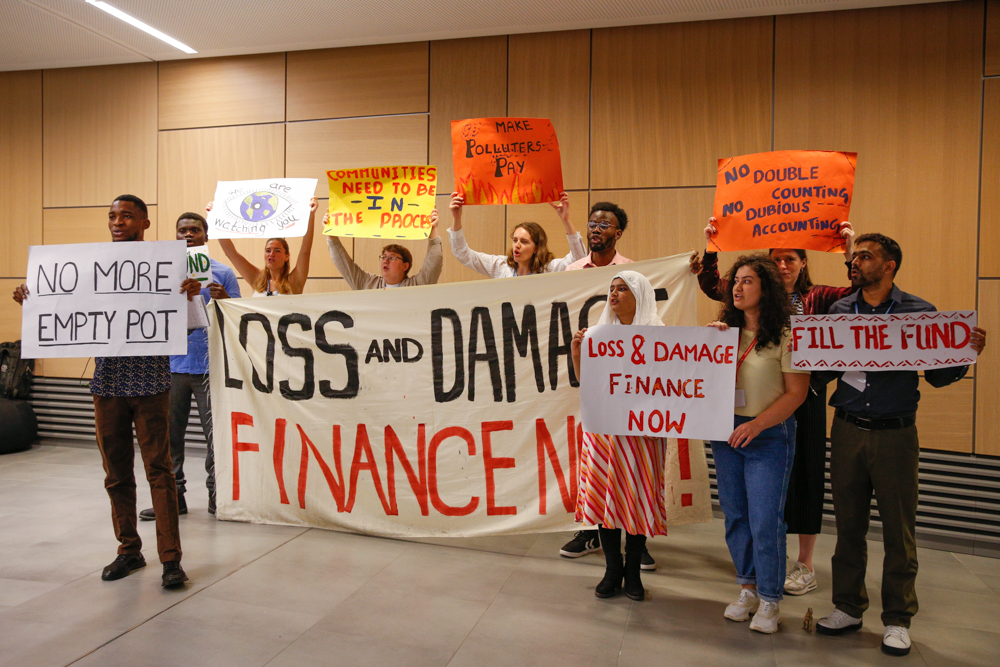

COP27 saw the long-awaited creation of a loss-and-damage fund to support victims of climate disasters. It was widely viewed as a victory for developing countries.

But that was far from the end of loss-and-damage negotiations. The Pakistani negotiator Nabeel Munir, who led the G77 and China group last year in their push for the fund, made this point early on at Bonn, in his new role as chair of the SBI:

“Make no mistake, there has been a fundamental change, a change that is positive…Yet the work has just begun.”

Discussions are now underway to decide where the money for the fund will come from, how it will be distributed and who will receive it.

Studies have estimated that, by 2030, climate-related disasters, such as hurricanes and sea-level rise, could cost developing countries at least $400bn each year. This sits within the broader context of developed countries failing to provide sufficient climate finance and a general lack of trust between parties around these issues. (See: Climate finance.)

The COP27 loss-and-damage decision involved setting up a transitional committee to develop both the fund itself and other “funding arrangements” to support relevant action.

The committee held its first meeting in Luxor, Egypt, in March, and its second in Bonn just before the talks opened. There will be two more before COP28, as well as a ministerial meeting.

At the close of the second transitional committee meeting, it was clear that the membership had already split along familiar lines.

Specifically, developed countries want to focus on “funding arrangements” outside the fund itself. This “mosaic of solutions” approach, previously supported as an alternative to the fund by the US and the EU at COP27, could include finance from multilateral development banks, insurance schemes and humanitarian organisations.

Developing countries, by contrast, wanted to see the loss-and-damage fund set up as an operating entity of the UNFCCC, funded by contributions from developed countries and delivering grants rather than loans.

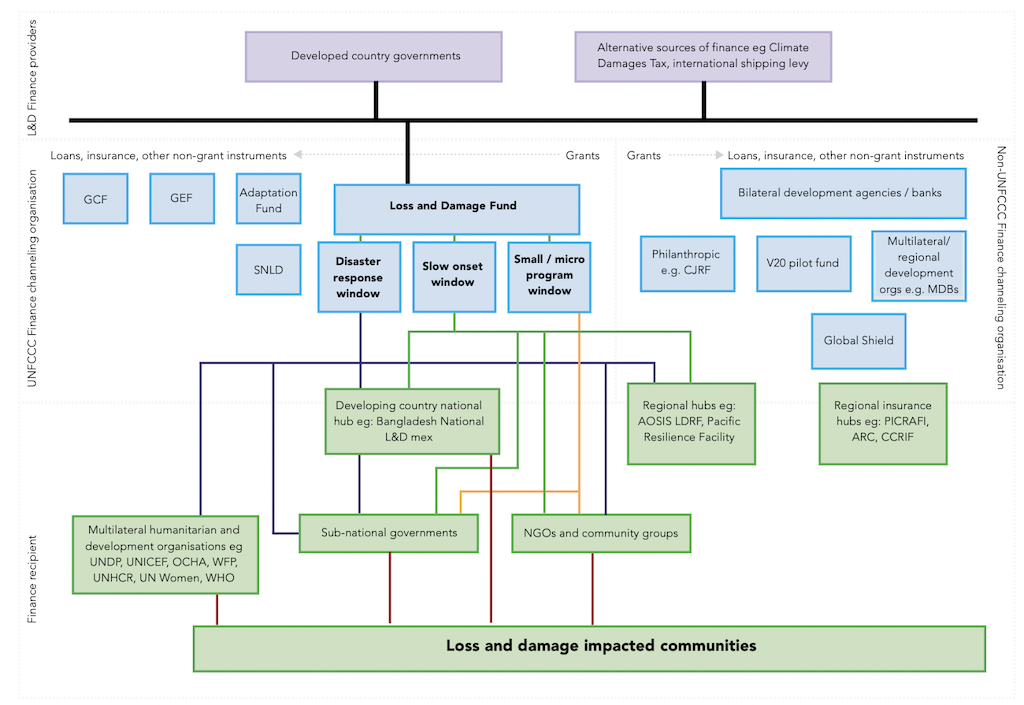

There are also discussions around supplementing this money with new sources of finance, such as taxes on aviation, shipping or fossil fuels. (See: DeBriefed, 16 June 2023.) The chart below gives a sense of how civil society groups see different sources of money going towards loss and damage.

At a press conference in the first week of Bonn, Mohamed Nasr, lead negotiator for COP27 president Egypt and a member of the transitional committee, said:

“This fund is not about development or reducing emissions, this fund is about regaining lost development achievements by developing countries. So if you lose a road, if you lose a grid, if you lose your livelihoods, you already were at a certain level, then because of the climate-induced disaster you went down.”

Given this, he said the developing countries were in agreement that existing systems, largely based on loans, would not be sufficient. Instead, he said loss-and-damage finance would need to be “grant-based or extreme, extreme, extreme concessionality”.

He also said that the funding should be open to all developing countries, but with different “triggers”, meaning some countries would be able to access funds more readily than others. (The question of who would be eligible was a major sticking point at COP27.)

Meanwhile, the Glasgow Dialogue, originally established at COP26 as a compromise when a loss-and-damage fund was not secured, continued into its second session at Bonn.

Last year, the dialogue was widely dismissed as a “talking shop” that would have little impact. Now, it is mandated to inform the work of the transitional committee and, therefore, proceeded as a venue in which parties could exchange views on how the fund could work.

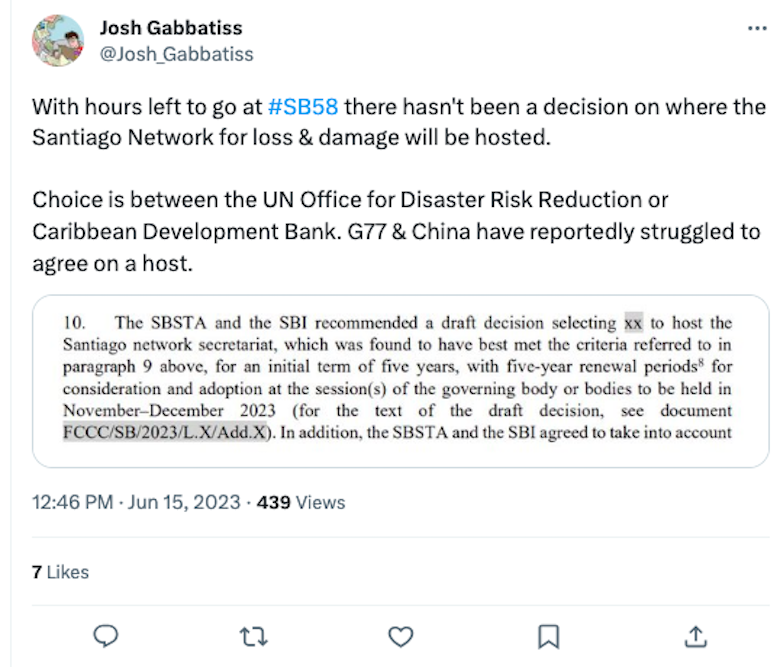

The only loss-and-damage element that was the subject of formal negotiations during Bonn was the question of where the Santiago Network for loss and damage would be located.

The network was established at COP25 as yet another compromise when loss-and-damage funding was rejected by developed countries. It has since been embraced by developing countries as an avenue to help them access support, but it initially languished as a mere UN website and has taken years to set up.

Harjeet Singh, head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network (CAN), tells Carbon Brief:

“It is going to play such a fundamental part in starting the technical assessments of what impact countries are facing…Hardcore technical capacity can be built by this institution if we get it right.”

This year, negotiators had to decide on a host organisation for the Santiago Network secretariat. This was supposed to be decided in Bonn so it could be waved through at COP28 later in the year.

They had the choice of two proposals, laid out in an evaluation report: the Office for Project Services in the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR/UNOPS), which would be based in Nairobi, Kenya; and the Barbados-based Caribbean Development Bank (CDB).

Discussions ended up stalling when developing countries could not reach consensus.

While both proposals were global south-based, AOSIS in particular wanted to see a Caribbean-based institution take on the network. AILAC, which has members in the region, also supported this option.

As the talks drew to a close, Paraguayan negotiator Agustin Carrizosa Bradshaw, from the Climate Youth Negotiator Programme, told Carbon Brief:

“I think the main issue here is that we all want to be represented as countries from the south…It is hard to find a place that represents us all and will give us quick access that is necessary for implementation of loss and damage.”

An AOSIS spokesperson tells Carbon Brief that the group’s position “is based on the merits of the institution, not the politics surrounding location”. They cited concerns about UNDRR’s background and experience, which they said is largely limited to “comprehensive risk management” and would not cover the full breadth of loss-and-damage issues.

Amid these disagreements about location, there were also concerns about the Santiago Network maintaining its independence. Heidi Maree White from the Loss and Damage Collaboration tells Carbon Brief developing countries were keen to insert safeguards to ensure the network would not be “pulled in different directions” by its host institution.

In the end, parties could not decide on a host for the network, leaving additional workload for COP28. The final text said the SBs “recommended a draft decision selecting xx to host the Santiago network secretariat, which was found to have best met the criteria”.

Adaptation

There were four key areas of negotiation with regards to adaptation in Bonn, namely, the global goal on adaptation (GGA), the Adaptation Committee, the Nairobi work programme, and national adaptation plans (NAPs).

Despite being established as one of the key pillars of the 2015 Paris Agreement, a number of key challenges have held back adaptation efforts, not least financing, where it lags behind mitigation.

As ambassador Wael Aboulmagd, special representative of the COP27 president explained during a press briefing in Bonn, adaptation simply does not attract private sector funding in the same ways.

“It’s just the reality. Look at the figures of where the private sector investment is going. You’ll find the lion’s share is going where? Renewables…because the business model is lucrative and they are simple and easy to understand.

“I am yet to see the business model that would make smart investors say: ‘Wow, I’m gonna go invest in adaptation.’

“What I’m getting at is it’s going to have to rely on creative sources of funding, not on the panacea of private sector with trillions of dollars.”

Beyond financing, adaptation is also harder to measure than mitigation, Carbon Brief was told by Bethan Laughlin, senior policy specialist at Zoological Society of London (ZSL). She explained that a mix of qualitative and quantitative metrics are required, which for the GGA must also be applicable to the varied experiences of communities around the world.

As Laughlin, explained in Bonn, it is easier to measure emissions and their reduction “than it is to measure adaptation in how much resilience a community has or how sustainable the ecosystem is, or whether species are thriving or declining, that they’re much harder metrics because it’s a mixture of qualitative and quantitative ”.

Additionally, adaptation is generally locally led and, most often, takes place on a small, community basis. This can provide an additional challenge to countries when it comes to measuring and communicating the adaptation efforts taking place, which, in turn, can limit the lessons that can be learnt and shared.

As Razan Al Mubarak, president of the International Union for Conservation of Nature said during a panel discussion at Bonn:

“The majority of the world is already adapting, but they don’t necessarily call that adapting, they call it surviving. It’s those survival stories and those solutions that are already ongoing and are on the ground that the global community needs to listen to and ensure that the so-called adaptation is indeed…within the climate-change discourse.”

Established at COP26, the Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme on the global goal on adaptation is a two-year programme designed to develop a clear framework for the GGA ahead of COP28, where it is supposed to be adopted.

Over the last year, the two-year work programme (2022-23) has held six workshops, with the latest taking place at Bonn over 4-5 June, and focusing specifically on metrics, indicators and methodologies for formally establishing a global adaptation framework.

Informal consultations were then carried out over the two weeks of talks, where division arose with Suriname on behalf of G77, China on behalf of the LMDC and India calling for the inclusion of targets as part of the framework within a series of submissions during the first week, with the G77 and China stressing the importance of moving “into substantive discussion on targets”.

India aligned itself with Suriname on behalf of G77, China on behalf of the LMDC, arguing that adaptation must be dynamic, and take into account the capacity of countries to adapt and the degree of climate risks they face. In a submission, India stated:

“Setting global goals for the reduction of vulnerability and reduced mortality from extreme events and climate-related disasters is absolutely necessary, but any goal on such outcomes, will have to be absolute in nature – such as say reducing mortality to zero for example. We cannot have a halfway target here as this would not be ethical. It is incumbent upon us, as Governments to ensure that not a single person is left behind. We may not always be able to achieve this in specific instances due to multiple reasons, but as a goal, we cannot have anything less than this.”

As talks continued into the second week, countries expressed their frustration at the GGA process, within the informal stocktaking meeting held by the SBI chair on Tuesday and attended by Carbon Brief.

For example, Costa Rica, on behalf of AILAC said it was “concerned” that talks had not advanced, and even more so by the “sense that there seems no will to reach an agreement on the framework at the COP28”.

As a result of the input during the informal discussions, parties were presented with three options for draft conclusions by co-facilitator Janine Felson of Belize, on Wednesday morning of the second week in Bonn.

These differed in a few ways. The first option – which was most popular with those in the global south, Carbon Brief was told – was the most substantive, due to the inclusion of an annex that provided elements for the development of the framework, while the second two provided a great level of flexibility – and were more popular with the global north – with a stronger focus on procedural conclusions.

We look forward to guidance by the SB Chairs on how we will deliver on the clear mandate regarding #GGA in line with parameters in paragraph 10 of the decision @shimwepya @AGNESAfrica1 @friphiri @COP28_UAE @UNFCCC @UNEP @ZeynWandati @adomfeh #SB58 #BonnClimateConference pic.twitter.com/TvlRVFSYoM

— AGN Chair (@AGNChairUNFCCC) June 14, 2023

Parties were divided on the options, with discussions continuing into the afternoon of the final day of Bonn. Madeleine Diouf Sarr chair of the Least Developed Countries (LDC) Group said in a statement following the end of the conference:

“We came here expecting to advance in our work towards adopting the framework on GGA at COP28 but negotiations had limited progress until the very last minute. This is concerning, given that GGA stands as one of our group’s main priorities, which is to enhance adaptation action and support for our countries.”

Ultimately, the third option, which provided a focus on the structure of the GGA was adopted following some wrangling over the wording and inclusion of links – Carbon Brief was told that half an hour was spent discussing the inclusion of a hyperlink.

Following the conclusion of the GGA sessions, Angelique Pouponneau, policy adviser to the AOSIS chair told Carbon Brief:

“AOSIS is working towards a GGA framework that does not create an invisibility of SIDS [small island developing states] and our special circumstances, while still advocating for enhanced collective action on a global scale. We think that the only way to do that is to have as much progress captured as possible, so it can inform subsequent workshops and the development of the GGA framework. We believe this is the outcome that we finally achieved at the conclusion of the negotiations.”

Beyond the GGA, other adaptation items progressed broadly without issue. Talks were undertaken within the Nairobi work programme, focused on addressing the gaps in adaptation efforts faced by countries, and it is now closed until next year’s talks in Bonn.

NAPs were put forward as a new agenda item for SB58 and adopted without the challenges seen on the MWP. Discussions during informal consultations focused on the challenges of implementing a NAP for developing countries, due to technical considerations as well as capacity constraints.

Forty countries have already completed their NAPs, with around 100 working on them.

Discussions within the review of the Adaptation Committee (AC) did run late, as parties debated the wording of the draft conclusions, with elements that will need to be concluded at COP28. As Emilie Beauchamp, lead for monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL)for adaptation at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) explained to Carbon Brief:

“That’s quite disappointing considering that the AC is doing good work – they are a strong technical body. They don’t have much resources and yet they’ve managed to turn over robust content from a technical point of view. So it’s a bit disappointing to see this lack of endorsement, which points to a lack of support for advancing work on adaptation across the Paris Agreement.”

Just transition

One of the more significant outcomes from COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh was the launch of a “work programme on just transition pathways”.

Calls for a phaseout of fossil fuels have been gaining traction, with activists and a handful of Pacific islands backing a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty in Bonn. This came after more than 80 nations expressed support for a “phase down” of fossil fuels at COP27.

In this context, climate-justice campaigners say the need for a just transition is greater than ever.

The negotiators in Bonn were tasked with fleshing out the programme. This included establishing its scope and what it would end up producing.

Over the course of the Bonn talks, the just transition work ended up falling into the same arguments seen in many of the other negotiations.

This is partly because supporting people as communities and societies are weaned off fossil fuels will cost money. This just transition negotiating stream is therefore another avenue that developing countries can use to seek climate finance.

From the outset, the G77 and China said their views were being overlooked in the talks, which they described as being “mitigation-centric”, according to Third World Network. Many developing countries envisaged a programme that took a broad, international perspective and included financial support and technology transfer.

By contrast, some developed countries came out strongly in support of sticking to language from the “preamble” of the Paris Agreement. This text references “imperatives of a just transition of the workforce” in accordance with “nationally defined” development priorities.

This is a more limited interpretation of the work programme’s role. Climate-justice groups interpreted this as meaning developed countries would only support just transitions on their own soil – as some are already doing.

In this vision, the work programme would involve a knowledge exchange between parties. Asad Rehman, executive director of War on Want, dismissed this approach at a press conference:

“They don’t want this work programme to result in any concrete action, any concrete targets, any concrete responsibilities. They simply want to talk about what’s best practice – well, we can send them an email.”

Speaking to reporters, ambassador Wael Aboulmagd, special representative of the COP27 president, emphasised an international and collaborative approach to the work programme that they introduced last year:

“We hope that the just transition approach will be conducive, because if you [leave] no country behind, I think we have a better chance of actually getting people on board and ensuring their buy-in in implementation.”

Ultimately, the talks yielded a lengthy “informal note”, which captured the full range of opinions. As a result, the document included developing country priorities such as international cooperation, more climate finance to support just transitions and even an “International Tribunal of Climate Justice and Mother Earth to address issues regarding just transition activities”.

However, this entire note is bracketed, meaning it is not agreed upon and will continue to be debated in future UN climate talks.

Separately, and despite all the arguments over the contents of the work programme, parties agreed to hold a workshop to hash these details out further. Even here, there was some last-minute tension as the EU reportedly objected to funding the event.

The final work programme text confirms that this workshop will be held before the next subsidiary body session at COP28 in Dubai, towards the end of the year.

“The big question is whether in Dubai the work will continue and we will be able to build a work programme that is fit for purpose,” Caroline Brouillette, executive director at Climate Action Network Canada tells Carbon Brief.

Article 6

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement covers international carbon markets and other “cooperative approaches” that nations could use to help meet their climate targets.

Carbon markets have received a lot of bad publicity in recent months. High profile investigations by news outlets and NGOs have suggested that many of the offsets purchased by corporations are not making a meaningful impact on emissions.

With this so-called “voluntary” carbon market facing such scrutiny, many nations and civil society groups want to ensure that the UN rules do not fall into the same traps.

Negotiations on this topic have now entered a deeply technical phase. The outcomes from Bonn remained largely procedural, with conclusions that called for further work and submissions from parties.

“Informal” notes captured some of the divergent views from different countries, on what has consistently been a contentious topic in UN talks.

Among the issues discussed in Bonn were transparency around the trade in offsets and whether parties can change their minds about issuing credits once they have already sold them. Both of these issues were fought over already at COP27 last year.

The Article 6.4 Supervisory Body has been set up to establish the rules for a new international carbon market, which is likely to begin operating in 2024 and will replace the old Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) market. The body held its fifth meeting the week before the main negotiations in Bonn.

This body has to come up with a series of recommendations on contested subjects. These include methodologies for calculating how many credits a project can issue and what the “baseline” of emissions would have been without the credits being bought.

Another topic up for discussion is how – or whether – carbon removals are included in this system. There are questions around whether both land-based and engineered removals would be counted, especially considering the lack of “permanence” in some removal projects – for example, if trees planted to suck CO2 from the atmosphere burn in a fire.

At the meeting, attendees agreed to drop the idea of “tonne-year accounting”, a methodology that has come under fire for not ensuring permanent carbon storage.

More meetings are set to take place over the course of the year. The supervisory body is due to make recommendations on these technical matters, which would then need to be agreed and approved by all parties atCOP28.

One notable topic discussed by parties during informal talks was the issue of “emissions avoidance”. This would involve payments for not carrying out an emitting activity – for example, agreeing not to open a new coal mine – but would not actually cut emissions.

As it stands, this is not an option under Article 6. However, the Philippines has been a consistent voice pushing for this option within the system. As Jonathan Crook, a policy expert on global carbon markets at Carbon Market Watch, tells Carbon Brief:

“That would be hugely problematic if you could credit on the basis of avoidance for…fossil fuel reserves that haven’t been exploited yet, the amount of tonnes that you could imagine that could generate…it’s massive.”

Opposition was captured in an informal note from the Article 6.4 talks, which noted that such credits would “rely on hypothetical scenarios and do not contribute to mitigation efforts”.

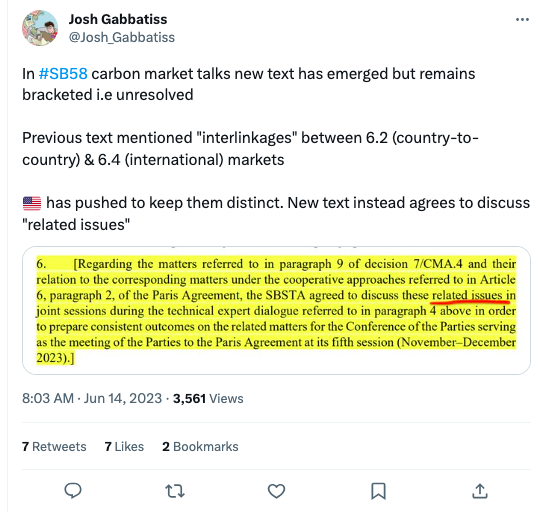

Meanwhile, discussions continued around Article 6.2, where countries trade climate action – termed Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) – directly with each other.

Some countries, notably Switzerland and Japan, have already begun exploring this system as a way to help meet their climate targets. Yet there are various technical issues that remain unresolved. Parties at Bonn agreed a manual should be created to help developing countries participate in Article 6.2 trading.

Once Article 6.2 credits are authorised, there is a requirement that “corresponding adjustments” are made by the country selling the credits, so emissions reductions are not counted twice.

Another question considered again in Bonn was whether a 6.2 credit can be revoked. Some parties want flexibility to take back their authorisation at a future date.

For example, if a highly forested country sells forest-based credits to other countries, but then realises it is not going to be able to meet its own climate targets, it might want flexibility to revoke its ITMOs. As Crook explains, this could lead to complications:

“The system they have in place [for Article 6.2], it’s extremely complex and changes to authorisation could lead to some issues.”

Another topic being debated was potential “consequences” if emissions data reported under Article 6.2 turns out to be inaccurate.

The UN system does not normally include punitive measures and some countries pushed back on the idea of consequences, while others favoured the idea that inconsistencies could be flagged in a centralised reporting platform.

While several developed countries argued that the Article 6.4 and 6.2 registries should be connected to ensure everything is centralised, the US objects to any such “interlinkages”.

Finally, Article 6.8 remains the least well-defined of the “cooperative measures” established under Article 6.

It does not consist of a carbon market but rather “non-market approaches”. This is therefore the preferred focus of some developing countries and civil society groups that object on principle to the concept of carbon markets, and their perceived negative impacts on communities in the global south.

Amid the wider failure of developed countries to meet their climate-finance obligations to developing countries, some, such as the US, have promoted carbon markets as a solution to the funding shortfall.

Some groups see Article 6.8 as an alternative to this – essentially an additional avenue to channel climate finance to developing countries. Souparna Lahiri from the Global Forest

Coalition explained this position in a statement ahead of the talks in Bonn:

“The Article 6.8 framework for non-market approaches ushers in the opportunity for the global south to find sources of climate finance to strengthen resilience and take real climate action, instead of surrendering land, resources and rights to the global north [via carbon markets].”

Discussions at Bonn continued around a “web-based platform” for Article 6.8, established at COP27, which some groups view as a potential means to link people in need with sources of finance.

Road to COP28

The UAE, which is due to host COP28 in December, has been under intense scrutiny due to its status as a major fossil-fuel producer and, particularly, the COP president’s role as chief executive of an oil company.

The COP28 team has pushed back against this criticism and emphasised the importance of involving fossil-fuel companies in the energy transition. However, so far it has given little indication of its ambitions for a successful event.

Alden Meyer, a senior associate at E3G and UN climate talks veteran, told journalists in a closing briefing that, in his view, the Bonn talks had been a “missed opportunity” for COP28 president Sultan Al Jaber:

“I think it’s fair to say that he’s still in a bit of a listening mode, rather than putting forward a concrete vision and set of objectives and strategies to achieve them that he wants to get out of the COP.”

This was the consensus in the limited press coverage surrounding the Bonn negotiations, including a Financial Times editorial titled: “Time is running out for the UAE to save its COP28.” Meyer said there would be more chances for Al Jaber to elaborate on his plans, for example, at the September’s UN general assembly in New York.

The Bonn talks made it clear yet again that climate finance has the potential to significantly disrupt negotiations. Less than a week after the session ended, many of the same delegates will gather in Paris, France, for a summit that aims to create a “new global financing pact” between the global north and global south.

Hosted by French president Emmanual Macron, alongside Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley, the event has the potential to yield climate-finance progress beyond the halls of UN negotiations.

India, in its capacity as G20 president, is also set to have a role in the Paris summit. However, together with US president Joe Biden and most global north leaders, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi will not attend the event itself.

Experts in Bonn told Carbon Brief that, while there were concerns around the summit, it could yield progress on debt relief and a carbon tax on shipping, which could be funnelled to countries in need of climate finance.

| Date | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 22–23 June 2023 | Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, Paris, France |

| TBC July | 7th Ministerial meeting on Climate Action (MoCA7) |

| 4–8 September 2023 | Africa Climate Week, Nairobi, Kenya |

| 9-10 September 2023 | G20 summit, New Delhi, India |

| 12–25 September 2023 | UN General Assembly (UNGA 78) |

| 18–24 September 2023 | New York Climate Week |

| 2 October 2023 | Climate and Energy Summit, Madrid, Spain |

| 8–12 October 2023 | Middle East and North Africa Climate Week, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

| 13–15 October 2023 | World Bank and International Monetary Fund Annual Meetings, Marrakech, Morocco |

| 23–27 October 2023 | Latin America and Caribbean Climate Week, Panama City, Panama |

| 30 November – 12 December 2023 | COP28, Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

-

Bonn climate talks: Key outcomes from the June 2023 UN climate conference