Ros Donald

19.05.2014 | 12:00pmBBC television coverage of the UN’s latest climate science reports was the most likely to portray climate science as not ‘settled’, according to emerging research. Meanwhile, UK tweeters are the most likely in the world to have debates about climate change

We’re reporting new communication research findings previewed at last week’s Transformational Climate Science Conference, hosted by Exeter University. The event was sunny, packed, and buzzing with different ideas about how climate communication is produced and received – including work reflecting on the Intergovernmenta Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s latest report. .

Old media – framing the issue

The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports have got lots of media coverage, and a team of researchers from Exeter University has been studying it. Presenting their results lead author Dr Saffron O’Neill said that of the main UK television channels, the BBC was most likely to present climate science as contested. ITV did in part, while Channel 4 stuck to reflecting the weight of scientific opinion on climate change, she said.

The findings are part of a research project identifying how different communications models or frames dominated print and broadcast media coverage of the new IPCC report.

The team identified 10 different frames. These included ‘settled science’ – in which the weight of scientific opinion is portrayed, and ‘uncertain science’ in which media organisations emphasised uncertainty in climate science and questioned humans’ role in climate change.

The research also discovered less used frames, like morality and ethics, security, and disaster. O’Neill suggests that the way the media talk about climate science helps set which policy options become acceptable and which are marginalised, shaping how the public and policymakers imagine and act on climate change.

James Painter, a former journalist and now head of the Journalism Fellowship Programme at Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for Journalism has also put television coverage under the microscope, investigating broadcast media reactions to the IPCC all over the world.

While most media researchers focus on print, Painter argues TV news deserves greater attention, pointing out that 4.5 million UK viewers still tune in to the News at 10 every evening – that’s a much larger audience than any newspaper could claim.

One of the preliminary findings of his research is that the so-called pause in surface temperature warming has been a topic of discussion in the UK and Australian media, but not in China, Germany, Brazil or India.

New media – the IPCC on Twitter

What about new media? When the last IPCC report was released in 2007, Twitter was barely a year old. But in 2014, it’s possible for researchers to examine how events like the IPCC get discussed on social networks in near-real time.

Of all the drivers for social media conversations, the Exeter researchers found media coverage dominated sharing and conversations about the IPCC on Twitter. Most Twitter shares were newsarticles, they said.

Dr Hywel Williams, who collaborates with O’Neill on Exeter’s IPCC project, said around 54,000 Twitter users tweeted about the reports over the months they were released. Of those, a hard core of around 2000 users tweeted about all three.

Using algorithms, the team was able to identify different communities of tweeters. Views across the Twitter landscape are polarised between those who are supportive of climate science and a minority who are more sceptical.

In a new published paper, the University of Nottingham’s Warren Pearce and co-authors also delved into the Twittersphere’s reaction to the IPCC release.

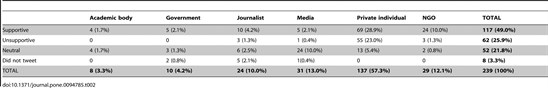

The researchers drilled down to discover the groups and individuals tweeting about the report in different countries and across different communities, mapping their interactions. It divides the tweets into three classifications: supportive of the IPCC, unsupportive and neutral. Most tweets were supportive: around half. A quarter each were either unsupportive or neutral.

Click image to enlarge

The chart below maps the structure of Twitter conversations about the IPCC. Each point is a user, and bigger points mean the user is better connected. The paper explains:

“Twitter users were manually coded according to the content of their tweets and Twitter biography within the population of tweets analyzed. Each node represents a Twitter user. Size of nodes is correlated with that user’s number of conversational connections. Climate change unsupportives, purple; climate change supportive, red; climate change neutral, green; did not tweet, light blue.”

Australian tweeters are located in the top right, and deserve a mention of their own. Despite its smaller population, Australian tweeters managed to tweet more than even the United States. Pearce suggests this is because climate change is so politicised in Australia.

While the map shows reaction to the reports was pretty polarised, the UK (bottom right) looked most likely to host interactions between supportive and unsupportive tweeters.

It’s also a pretty active hub for climate conversation, to say the least. Pearce tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a small, active, community of UK tweeters who have a rich, but robust conversation about climate change despite having a very wide range of views. These are not just people who are shouting loudly without anyone listening, but participants in interesting, and often enlightening, conversations about climate science and policy.”

New boundaries

The majority of studies investigating trends in media coverage focus on the written word in the mainstream press. So pushing new boundaries doesn’t just mean adding so-called new media like Twitter and the blogging community into the mix. It also involves gaining a greater understanding of climate discourse on television, a medium you’d be hard-pushed to describe as new.

At the same time, charting the progression of the climate story in the print media is vital for communication researchers. As the field of climate change communication research gets more complex, so too does it capture more of the conversation.