Autumn budget 2021: Key climate and energy announcements

Multiple Authors

10.27.21Multiple Authors

27.10.2021 | 6:32pmThe UK’s chancellor Rishi Sunak has delivered a spending review and his third budget, just days before the country hosts the COP26 climate summit.

The budget sets out the government’s tax and spending plans for the year ahead, while the spending review sets departmental budgets up to the financial year 2024-25.

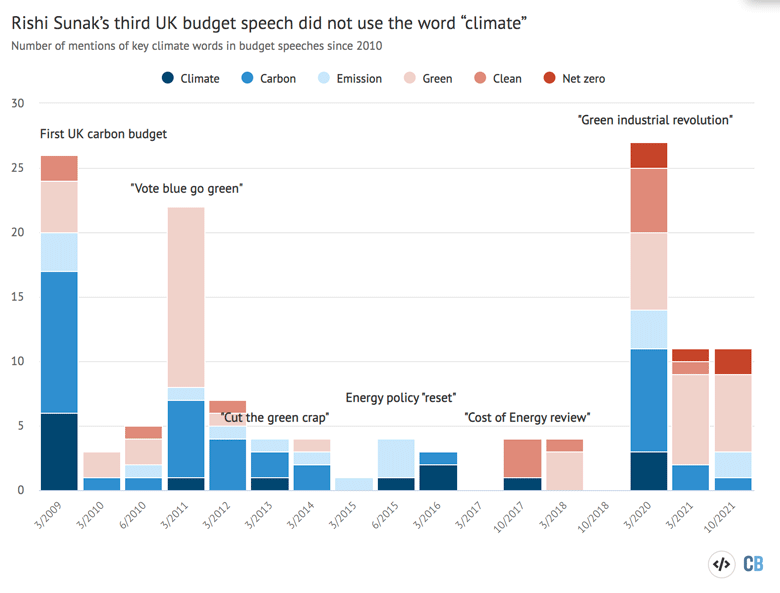

In a budget speech that failed to use the word “climate” even once, Sunak said he would cut the rate of “air passenger duty” on domestic flights and freeze fuel duty for a twelfth consecutive year.

He also said that the UK would continue to breach its domestic legal obligation on giving overseas aid worth 0.7% of gross national income until 2024-25.

Sunak’s budget promises up to £1.7bn in direct government support to enable another new nuclear plant to be signed off during this parliament and follows a decision to go ahead with the “regulated asset base” model to pay for the technology.

His spending review also set out plans for £30bn in public investment across government departments, most of which has been set out in a series of sectoral plans and the recent net-zero strategy.

Below, Carbon Brief explains all the key climate and energy announcements contained within both the budget and the spending review.

Net-zero

The chancellor’s budget speech was notably light on references to climate change or the government’s net-zero strategy, published just a week earlier.

This is despite the fact the Treasury said last week that “action to mitigate climate change is essential for long-term prosperity”. Yesterday, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) identified “proper funding and/or incentives” as an area of significant delivery risk for net-zero.

Sunak did not use the word “climate” at all in his speech, which stretched to more than an hour. He waited until the second half of his speech to mention “net-zero” and used the phrase only twice, as the chart below shows (red chunk). Sunak also used the word “green” six times.

Nevertheless, the Treasury “red book” itself, which sets out the budget plans in detail, argues that the the budget and spending review, in combination with the net-zero strategy, keeps the UK on track for its climate targets:

“Taken together, this spending package, along with bold action on regulation and green finance, will keep the UK on track for its carbon budgets and 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution, and support the pathway to net zero by 2050. It does so in a way that creates green jobs across the country, attracts investment, and ensures energy security.”

The document mentions “net-zero” some 57 times and “climate” 36 times, more than the seven and nine mentions, respectively, in the budget red book published earlier this year.

Recalling the title of the net-zero strategy, the red book says the budget and spending review “sets out the government’s plans to build back better over the rest of the parliament”.

The document touts “public investment for the green industrial revolution” of £30bn since March 2021 (see the section on the spending review, below), including £1.7bn “to enable a final investment decision for a large-scale nuclear project in this parliament” (see: new nuclear).

In addition, the Treasury is giving the National Infrastructure Commision an additional objective to consider how its advice can “support climate resilience and the transition to net-zero”.

UK govt has added net-zero to the remit of the National Infrastructure Commissionhttps://t.co/hXIZnTnVI6 pic.twitter.com/1uKq08GFVk

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) October 27, 2021

Last week’s net-zero strategy had set out an intention to rebalance energy levies and taxes on electricity relative to gas, however, this is not taken up in the budget and spending review.

A recent report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) noted that incentives are currently highly uneven, with household use of gas being “effectively subsidised”. It said:

“Overall tax rates on emissions vary wildly, including by the source of the emissions and the type of end user. The incentives to cut emissions are therefore highly uneven…This makes reducing carbon emissions more costly than it needs to be.”

Finally, the chancellor said that the UK would not meet its legal obligation to spend 0.7% of gross national income on overseas aid until 2024-25, with money only set aside to bridge the current gap on a provisional basis. (The budget reiterates that UK climate finance is set to double.)

The wider cut to overseas aid has been seen as a barrier to UK attempts to persuade other countries that they should increase the provision of climate finance ahead of COP26. Rich nations are currently still short of the $100bn in climate finance that they pledged to provide by 2020.

Air passenger duty

A standout statement from Sunak’s speech was a pledge to cut air passenger duty in half for domestic flights, making air travel within the UK cheaper.

As a result of the new domestic band for the duty, set at £6.50, the Treasury estimates that 9 million passengers will pay less for flights in 2023-24.

Framed as an example of “seizing the opportunities of Brexit,” the move was met with surprise by many given the government’s net-zero target, the proximity of the COP26 summit and the widely understood need to curb emissions from flying.

If anyone was worried about the lack of climate talk in this speech, don't worry because the chancellor just announced that UK domestic flights will have air passenger duty cut in half 👍 #Budget21

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) October 27, 2021

In fact, only the day before, the Climate Change Committee, which advises the government, noted in its assessment of the net-zero strategy that the plan had “nothing to say…on limiting growth in flying”.

The CCC also suggested that “government leadership, public engagement and wider policy” could encourage a shift away from flights.

The move by the Treasury follows a consultation and lobbying from the UK’s airlines sector, which has pointed out that internal flights in the UK can be more expensive than flights to Europe across similar distances.

New FOI

— Zach Boren (@zdboren) May 10, 2021

doc shows UK airline industry lobbied for the tax cut on domestic flights that the government is now consulting onhttps://t.co/dD9m8TVxcR pic.twitter.com/5Ny2uDXpBd

As a comparison, train travel across the UK is generally far more expensive than air travel and campaigners pointed out that most domestic flights can be replaced by train journeys with just one seventh of the carbon footprint.

Indeed, various climate NGOs and thinktanks have argued for a frequent-flyer levy on flights rather than additional cuts to the cost of flying. Others have pointed out that domestic flights are already subsidised in the UK as they are not subject to VAT or fuel duty.

However, the chancellor noted in his speech that international flights contribute more to UK aviation emissions than domestic ones and he mentioned another plan to add a new ultra-long-haul distance band to air passenger duty.

According to the spending review document, this will align it “more closely with environmental objectives by ensuring that those who fly furthest incur the greatest level of duty”.

New nuclear

On the day before the budget, the government published plans to support new nuclear capacity through a “regulated asset base” (RAB) funding model, claiming it would save “£30bn on each new power station”.

We’re lowering the cost of new nuclear ✅

— Dept for BEIS (@beisgovuk) October 26, 2021

Our finance model will cut costs for developers and save consumers over £30bn on each new power station.

Reducing our reliance on gas & providing low carbon power to help us reach #NetZero by 2050.

➡ https://t.co/AQkUqPq3R1 pic.twitter.com/dxMVbxPYsz

Instead of paying for the electricity generated by a new nuclear plant only once it starts operating, as under the existing “contracts for difference” (CfD), the RAB model would see consumers starting to pay as soon as reactors are being built.

Effectively, the RAB shifts some of the risks of construction from the nuclear developer to UK consumers, with the details depending on the precise design of the legislation. In return, the government assumes this will lead to reduced financing costs with lower risk premiums for lenders.

This risk transfer explains why government officials had previously rejected the RAB design.

The decision follows a consultation in 2019 and is designed to enable a final investment decision on one more large new nuclear plant during the current parliament, as pledged previously.

The leading contender for this is the Sizewell C new nuclear plant in Suffolk, which would be a copy of the scheme currently being built at Hinkley C in Somerset by French utility EDF.

An impact assessment published alongside the proposals sets out how the government thinks the new funding model would save money, by reducing the cost of finance to support construction.

It says the RAB would cut finance costs from 9% in the case of Hinkley C, which will cost consumers £92.50 per megawatt hour (MWh) in index-linked 2012 prices, to between 4-6% for a future new nuclear plant.

Carbon Brief analysis suggests the lower financing costs and the savings claimed by the government would imply a price of around £60/MWh under the RAB model.

In addition to the new funding scheme, the budget promises up to £1.7bn of direct government funding “to enable a final investment decision for a large-scale nuclear project in this parliament”. The red book adds: “the government remains in active negotiations with EDF over the Sizewell C project”.

Spending review

While the chancellor did not give much indication of it in his speech, the budget and spending review document itself contains a section titled: “Building back greener,” It outlines in detail the government’s spending plans for achieving its net-zero target.

The vast majority of the measures and funding packages mentioned in the document have been announced over the past year, in sector-specific strategies on transport, buildings and more, as well as in the net-zero strategy itself.

However, according to the Treasury, the document “builds on” the £26bn of climate-related investment quoted in the net-zero strategy and brings the total announced since March 2021 up to £30bn. This includes £15bn for the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) alone.

Among the new funds making up this additional £4bn are the £1.7bn for a new nuclear power station (see above), as well as more money for zero-emission buses and nature restoration.

Campaigners and environmental groups have stated that the public spending announced by the government so far has not been in line with its net-zero goals.

The #SpendingReview2021 must pledge an extra £21 billion per year in public investment to get the UK on track for #NetZero

— Green Alliance (@GreenAllianceUK) October 27, 2021

Will @RishiSunak close the gap? pic.twitter.com/LLHwYur2JS

After the heat and buildings strategy failed to live up to public-funding expectations for many, some policy experts pinned their hopes on the Treasury to make up the shortfall in its budget announcement.

Along with industry, the CCC identified this sector as less secure in terms of funding and incentives to achieve net-zero.

Instead of announcing new money, the spending review only reiterated the £3.9bn to support home insulation and low-carbon heating that was announced in the heat and buildings strategy.

According to thinktank E3G, this is the “greatest investment gap in green spending” – nearly £10bn short of what is required for net-zero. The Conservatives also pledged to spend £9.2bn by 2030 on energy-efficient homes in their 2019 election manifesto.

Separately, the document does mention new business rates relief from 2023 that will support investment in property improvements and help businesses “make improvements to their premises that support net-zero targets”, among other things.

The spending review also confirms that a total of £6.1bn will be spent to support the government’s transport decarbonisation strategy, although most of this comes from funding that had already been announced.

While this includes around £5bn for buses, walking and cycling, it is dwarfed by the £24bn between 2020-21 and 2024-25 set aside for road building and maintenance in England, plus the £8bn for filling potholes.

We’re helping local transport, everywhere:

— Rishi Sunak (@RishiSunak) October 27, 2021

🚗A long-term pipeline of over 50 local roads upgrades.

🕳Over £5bn for local roads maintenance, enough to fill 1 million more potholes a year.

🚲And funding for buses, cycling and walking totalling more than £5bn. #SpendingReview pic.twitter.com/zOEWNXj4Dv

This focus on road expansion has been a consistent point of contention for UK climate policy experts, especially given that the government has not included policies to curb road traffic in its net-zero plans. This omission has been highlighted by the CCC.

Another funding announcement with potential climate significance was a commitment to increase annual public R&D investment from £14.9bn to £20bn, rising to £22bn by 2026-27.

This was broadly welcomed by the research community, who, nevertheless, noted that it involved pushing back the £22bn target by two years.

The government has also pledged to spend £1.5bn specifically on net-zero innovation, although this was already announced in the net-zero strategy.

A document published as part of the spending review includes a set of “priority outcomes” for government delivery, based around five “missions” set by the prime minister. One of these missions is the net-zero target, specifically:

“Net-zero: To get our country well on the way to net-zero carbon, supporting green jobs and a better environment for the next generation.”

The Treasury red book says the decisions in the spending review have been “informed” by their expected contribution to the net-zero target. It says:

“SR21 decisions have been taken based on how spending will contribute to the delivery of these [priority] outcomes. For example, investment decisions have been informed by data and evidence on the expected contribution of proposals to meeting net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and assessed within the context of the broader suite of policies set out in the Net-Zero Strategy.”

(The CCC has proposed a more stringent “net-zero test”, which would “ensure that all policy and planning decisions are consistent with the path to net-zero”. The Treasury has not adopted this.)

The Treasury says that meeting the 2050 net-zero target is a cross-government “priority outcome” and progress will be measured at departmental level against a series of metrics.

None of the priority outcomes or metrics for the Treasury relate to net-zero.

For the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), metrics include overall and sectoral greenhouse gas emissions, as well as the low-carbon share of electricity generation, progress towards the target of 600,000 heat pumps being installed per year by 2028 and the “policy gap” to meeting legislated carbon budgets.

Progress against the heat-pump target will be reported annually. Regarding the policy gap, it says:

“[This] is calculated using data published in the BEIS Energy Emission Projections. This metric will be updated for internal reporting when the projections are next updated.”

For the Department for Transport, metrics include: greenhouse gas emissions from domestic transport; new sales of zero-emission vehicles; rail carbon emissions per passenger and freight kilometre; and the share of trips taken by walking, cycling or public transport.

The department does not have a performance metric associated with aviation emissions.

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) has a “priority outcome” of ensuring “more, better quality, safer, greener and more affordable homes”. However, none of its metrics are measures of domestic energy efficiency or greenhouse gas emissions.

Separately, the budget also freezes the rate of the UK’s “carbon price support” (CPS), a top-up carbon tax on power stations burning coal, oil or gas, which is paid in addition to prices under the UK Emissions Trading Scheme. Keeping the CPS at £18 per tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) from 2023-24 will cost the Treasury some £15m per year, it says.

Fuel duty

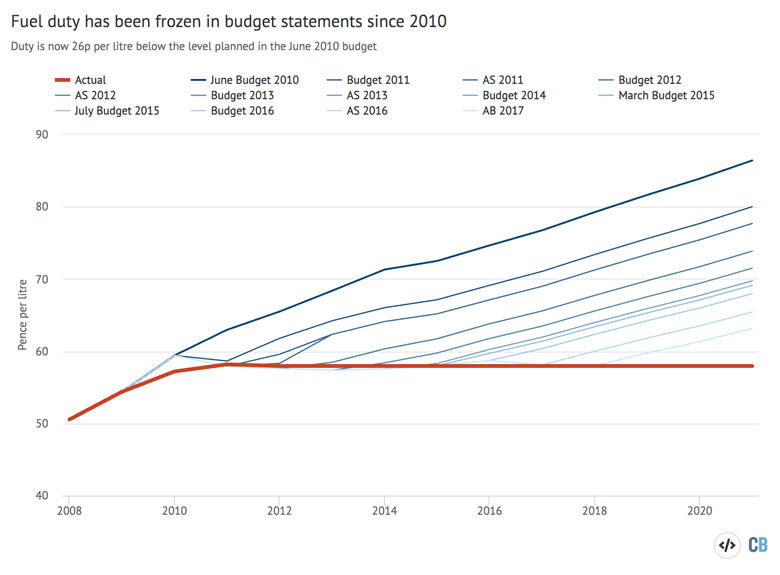

Sunak used his budget speech to confirm that fuel duty will remain frozen for a “twel[fth] consecutive year” during 2022-23. The tax, levied on sales of petrol and diesel, has remained at a rate of 58 pence per litre, plus VAT, since 2011.

According to the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) this amounts to a 20% cut in real terms.

At the March budget, the Treasury’s “red book” had said: “Future fuel duty rates will be considered in the context of the UK’s commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.”

However, with fuel prices nearing record levels, Sunak has once again shied away from allowing duty to rise with inflation. The latest freeze will cost the Treasury more than £1.5bn a year in lost revenue, according to the government’s own policy costings, which take account of “the increase in consumption in response to lower fuel price increases as a result of the measure”.

Instead of rising with inflation, fuel duty has now been frozen for more than a decade, as the chart below shows. This is a large tax cut for motorists, with successive freezes adding up to more than £10bn a year and having cost the Treasury more than £100bn in total.

In an October report, the IFS once again criticised the freeze, saying:

“Despite apparently wanting people to move over to low-emissions cars, the government has frozen fuel duties for more than a decade (a real-terms cut of almost 20% since 2010–11) – but never as a stated long-term policy, typically announcing one more year’s freeze with inflation uprating assumed to recommence thereafter.”

The report, like the Treasury’s own review of net-zero, published last week, highlights the fact that in the longer term, fuel duty will be eroded as drivers switch to electric vehicles. The institute argues in favour of a shift to road pricing “as quickly as possible”.

A recent report from the Resolution Foundation called road pricing “the only plausible option” to replace the long-term decline in receipts from fuel duty. However, it said that uprating fuel duty in the short term would have “help[ed] both the public finances and decarbonisation”.

Indeed, Carbon Brief analysis published last year found that, overall, UK carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions were up to 5% higher than they would have been without a decade of fuel duty freezes. The UK’s cars are now responsible for higher CO2 emissions than its power plants.

In contrast to the real-terms cut in the price of driving, public transport fares have often gone up faster than inflation, creating an ever-increasing cost differential. Confirming the latest increase in rail fares of 1% above the rate of inflation, the government said last December that it “reflected the need to continue investing in modernising the [rail] network”.