Simon Evans

12.09.2014 | 3:50pmThe UK’s households could end up paying for expensive new power stations which are not actually needed, according to a committee of MPs.

They are concerned about the government’s approach to the UK’s shrinking electricity supplies. They say its capacity market plans risk locking in unnecessary high-carbon generation, potentially adding £359 million to energy bills and increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

We’ve delved into the government’s historical electricity data to show how the UK’s electricity use has changed, why the government thinks a capacity market is needed and why the MPs say it’s got things wrong.

Capacity to meet demand

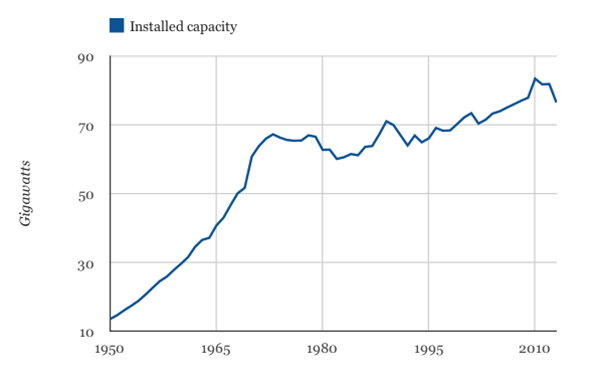

The UK’s electricity generating capacity has changed a great deal over the past century. Back in 1950, there were 13 million users connected to the electricity supply network and the nation’s power stations had the capacity to produce 14 gigawatts of electricity (chart, below).

Over the course of the intervening decades the amount of electricity required in the UK has rocketed, with capacity exceeding 80 gigawatts and the number of connected users reaching nearly 30 million.

UK installed electricity generating capacity. Source: DECC

In recent years however, the amount of generating capacity in the UK has started to shrink as power plants close. That’s a concern for government – no-one wants to be in charge when the lights go out.

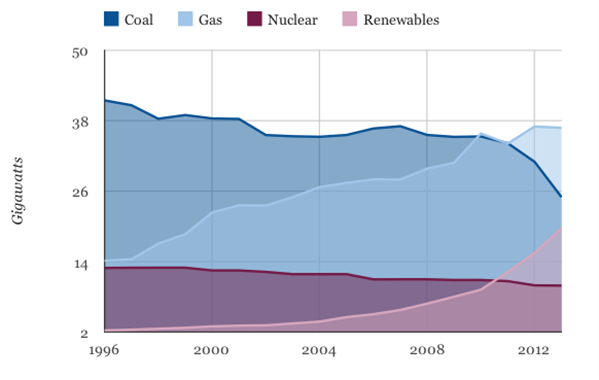

In order to understand why this is happening, it helps to unpack things a little. The capacity shrinkage is largely down to aging coal (dark blue area, below) and nuclear plants (purple) being closed down.

Source: DECC

While this has been happening, there has been a surge in renewable power capacity (pink area), led by the rapid construction of windfarms across the UK.

It’s important to remember however that windfarms only produce electricity when it’s windy. So the amount of power you get for each megawatt of wind capacity installed is much lower than for coal, gas or nuclear.

Capacity crunch

The recent trend of coal plants closing down is very much expected to continue. Gas plants are starting to struggle financially too, raising fears of a capacity crunch.

That’s why the government is bringing in a capacity market. This will pay power companies a retainer, simply for having generating capacity ready and available. They will get the money whether their capacity is needed or not. This December companies will be able to start bidding for contracts on the capacity market, due to kick off in 2018.

The capacity market presents a difficult balancing act. If this market were to support new gas plants being built when they aren’t really needed, it would amount to consumers subsidising unnecessary high-carbon generating capacity. But if capacity is falling, surely something must be done to keep the lights on?

Well, yes and no. Because as capacity has started to decline there has been another, more surprising change in the electricity sector.

Declining demand

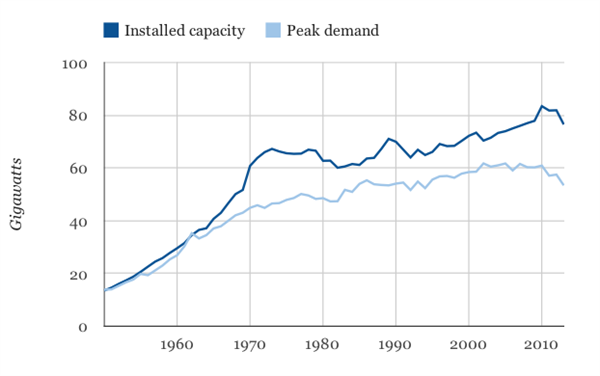

After rising almost continuously throughout the 20th century, UK electricity demand has started falling. Despite a rising population and ever-growing demand for gadgets, it’s been falling since the mid-2000s.

In fact, peak demand (light blue line, below) has fallen more than capacity (dark blue). That means the buffer of installed capacity over peak demand has actually grown in recent years.

Source: DECC

So you might think fears over the capacity crunch are misplaced. But don’t forget that coal plants are projected to carry on closing and the renewables replacing them put out fewer megawatt hours of electricity per megawatt of capacity installed.

Once you take capacity factors and future plant closures into account, the capacity margin is widely expected to fall to very low levels by winter 2015/16, and as if the situation wasn’t tricky enough, the capacity margin has also been squeezed by nearly 4 gigawatts-worth of unexpected shutdowns this year.

That aside, what the fall in demand demonstrates is the potential to avoid building new power stations completely. Using less electricity would be cheaper than building new capacity, and it should help reduce emissions at the same time.

Demand uncertainty

So why aren’t we managing demand better?

Part of the reason is that, incredibly, no-one is completely sure why demand has fallen so much. Falling electricity use in homes is partially responsible, driven in part by energy efficient lighting and appliances. Rising electricity prices have undoubtedly been a factor too. But uncertainty over the exact causes helps explain government reluctance to rely on demand reduction potential when insuring against future blackouts.

Step forward a range of companies who say they can offer more predictable demand reduction services. By co-ordinating factories or business premises to use less power at peak times or switch to back-up generators, these companies suggest they can chip away at peak electricity demand.

These ‘demand side response’ firms will be allowed to bid in the capacity market auctions, but they say their participation will be limited by the auction rules.

According to a report prepared for three firms in the demand management sector, demand side response could save up to £359 million on energy bills in the first year of the capacity market. But in order to realise this saving and the potential avoided emissions, the capacity market rules would need amending, MPs on the ECC committee say in a letter to energy minister Matthew Hancock. They write:

“If [the] design faults are not rectified, the system could encourage the construction of expensive new power stations which are not actually required. The result of this will be to lock in unnecessary high carbon generation capacity instead of innovative demand side solutions, leading to higher bills for electricity consumers and increased greenhouse gas emissions.”

With the climate and consumers’ pockets set to benefit, the MPs argue that’s a change worth making.