Simon Evans

19.03.2015 | 6:00pmGovernment claims to be leading the world on emissions reductions have been challenged by new research, the BBC reports today.

The BBC says UK emissions are rising, not falling, once pollution in imported goods from the likes of China are included. In fact, UK emissions including imports are below 1990 levels, while a larger share of the UK’s imported emissions come from Europe than from China.

Carbon Brief explores the new research on the UK’s imported emissions, and considers the implications for global climate politics.

Consumption versus production

Traditional emissions accounting only considers the greenhouse gases generated within a country’s own borders. In other words, emissions produced in the UK are allocated to the UK. On this measure, UK emissions have fallen dramatically to around 25% below 1990 levels.

But this impressive record is illusory, the BBC report says, because of emissions embedded in imported goods. This is not a new idea. For instance, this 2012 Guardian article reports MPs’ claims that the UK has “merely outsourced emissions to China”.

Consumption-based accounting attempts to acknowledge this issue, adding up its impact on the UK’s total climate footprint. It adds emissions embedded in imports to the UK’s footprint by tracking global trade from the point of purchase of goods and services back to their origin.

If someone in the UK buys an Audi or an iPhone, then the UK is handed responsibility for the emissions needed to make them. Using this method, new research from the University of Leeds finds the UK’s record looks less impressive, with emissions in 2012 just 7% below 1990 levels.

Imports mostly not from China

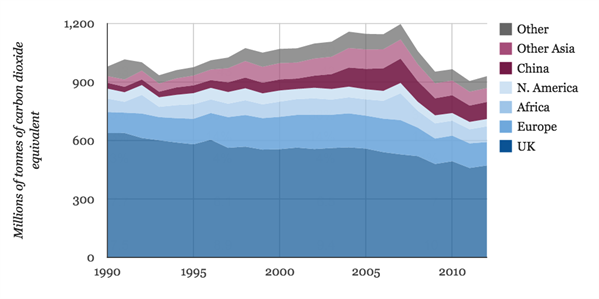

The UK’s imported emissions have increased over the past two decades so that they now make up around half of the UK’s climate footprint, as the chart below shows. The UK’s production emissions have fallen fast (dark blue area), but imports have offset much of the gain (lighter blues, purples and grey area).

Source: University of Leeds Sustainability Research Institute. Graph by Carbon Brief.

It’s worth noting that most of the UK’s imported emissions are not from China, however, contrary to popular perceptions. About a quarter of imported emissions come from Europe and around a fifth from China, with roughly another fifth coming from Africa.

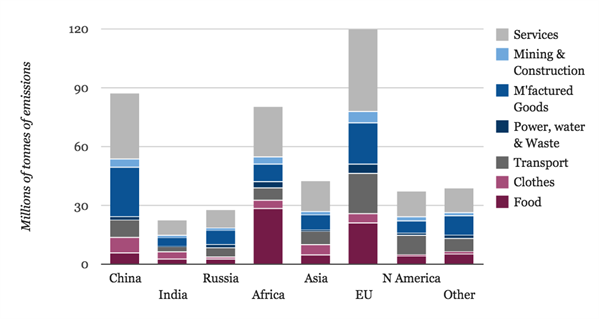

So, which types of goods and service bought by UK consumers are driving imports of emissions from overseas? The new research contains surprises here, too, apparently at odds with the popular view that what has happened is UK outsourcing its manufacturing industry to China.

In fact, manufactured goods (mid-blue chunks, below) are not the main source of imported emissions for any region, not even for China.

Source: University of Leeds Sustainability Research Institute. Graph by Carbon Brief.

The chart’s accounting counts mobile phone contracts that come with a phone as a service (grey chunks, above), along with the whole public sector and food bought in restaurants. Any emissions produced while providing these to the end user are counted as services.

Climate politics

So, what does all this mean for climate politics? One of the biggest challenges for global climate talks it around how to divide up emissions-cutting effort fairly. If UK consumption is driving emissions overseas, perhaps it would be fair to make the UK responsible.

India has hinted it would like to shift towards consumption-based responsibility for emissions, a move that some say could unlock stalled climate talks. The idea does not feature in the draft UN climate negotiating text, however, which contains wording contributed by all countries.

China, the US, the EU and India are the world’s top four emitters, in that order, using either accounting method. China remains number one under consumption-based accounting, even though about 16% of its emissions are related to products for export overseas.

But there might still be a role for consumption emissions at this year’s climate talks. Prof John Barrett, lead author of the new UK consumption emissions research, tells Carbon Brief:

“It seems to me the greater the emissions effort the EU can put forward, it gives less and less room for others to walk away from a [climate] deal and say you’re not doing your bit.”

For instance, Barrett’s research suggests the UK should bring forward its target to cut emissions by 80% emissions against 1990 levels by 10 years, from 2050 to 2040, or even earlier.

The UK’s reliance on imported emissions is relatively unusual, however. Imported emissions make up around half the UK’s footprint and it is the second highest net importer of emissions in the world. Nick Mabey, chief executive of thinktank E3G, tells Carbon Brief most countries import only 10 or 15% of their footprints.

The UK’s situation is less a case of outsourcing factories overseas and more a case of it consuming more in a globalised world, says Barrett. UK manufacturing hasn’t decreased that much, he says, but imports fuelled by cheap labour have met growing demand.

Conclusion

Territorial emissions accounting might not be perfect, Mabey says, but in terms of simplicity it is the more practical approach. Lord Deben, chair of the UK’s Committee on Climate Change, told the BBC the UK only has direct control over its home-grown emissions, whereas manufacturing methods and energy choices in China are outside our control.

Barrett says consumption accounting brings additional information to the table, but agrees there’s no need to abandon territorial accounting methods. Instead, he says consumption emissions highlight how hard it is to decouple emissions from economic growth.

That’s why many commentators were so surprised that carbon emissions stalled in 2014, even as the global economy expanded. For a good chance of limiting warming to below two degrees, the challenge of decoupling emissions from growth will have to be cracked.

-

Are the UK's emissions really falling or has it outsourced them to China?