Arctic summer sea ice to disappear with 2C warming, study says

Robert McSweeney

11.03.16Robert McSweeney

03.11.2016 | 6:00pmA new study, published in Science, pinpoints the direct relationship between carbon emissions and the amount of Arctic sea ice melt they cause as the climate warms.

For every tonne of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere, summer sea ice cover in the Arctic shrinks by three square metres, the researchers say.

For context, three square metres is a bit bigger than a standard UK pool table. And a tonne of CO2 is average emissions of a UK citizen every seven weeks.

If the same relationship holds in the coming decades – which the authors are confident it will – this means they can pin down how much more CO2 it will take before the Arctic is sea ice-free in summer.

The number they come up with is 1,000bn tonnes, or one trillion tonnes. This is the same as the IPCC’s carbon budget in 2011 for keeping global temperature rise to no more than 2C. The lead author tells Carbon Brief this means that with 2C of warming, “Arctic summer sea ice is gone”.

Return trip from London to New York

The end of the northern hemisphere summer is a key point in the Arctic calendar. It’s when the annual melt season comes to a close and sea ice reaches its smallest extent for the year.

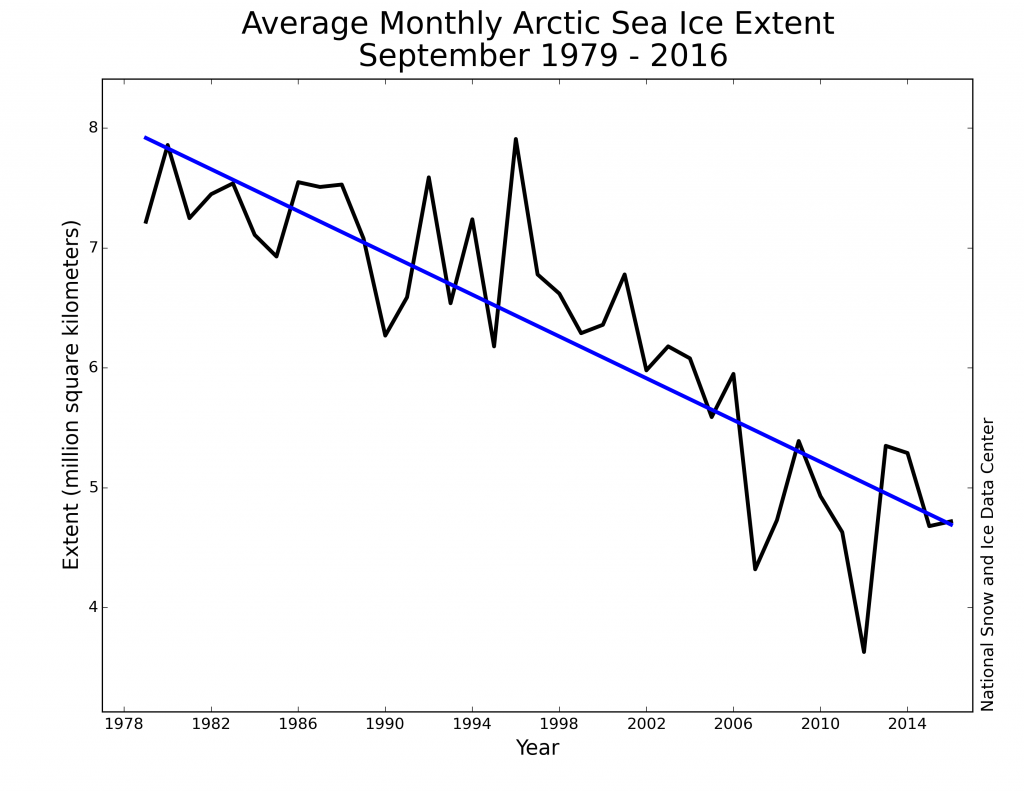

Arctic sea ice extent is declining in every season, but it’s in the trend from one summer to the next that the reduction is most pronounced. Since the beginning of the satellite record in 1979, Arctic sea ice cover in September has decreased by around 13% per decade.

CAPTION: Average Arctic sea ice extent for the month of September between 1979 and 2016. Black line shows annual data, and blue line shows the long-term trend. Credit: NSIDC

The new study highlights how the observed decline in September sea ice has a near-perfect relationship with the amount of CO2 that humans have emitted.

Using data on September sea ice extent stretching back to 1953, the researchers find that three square metres of sea ice has been lost for every tonne of CO2 emitted from burning fossil fuels and producing cement.

Looking at sea ice loss in this way highlights the impact of emissions, says lead author Dr Dirk Notz, head of the sea ice research group at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology.

This relationship doesn’t account for emissions from other greenhouse gases or other sources of CO2, such as those from land use change. While the impact of other gases is comparatively small, says Notz, including them would make the “three square metres” number a bit smaller.

It’s also worth noting that the loss of sea ice doesn’t happen immediately after the CO2 is emitted – although the time lag is likely to be only a few years, says Notz.

Ice-free summers

Scientists are interested in predicting when the Arctic will first become sea “ice-free” in summer – defined as the point at which sea ice extent falls below one million square kilometres. Using the relationship outlined in the new paper, the researchers calculate that another trillion tonnes of CO2 emissions would be enough to bring Arctic sea ice in summer below this threshold. Notz explains to Carbon Brief:

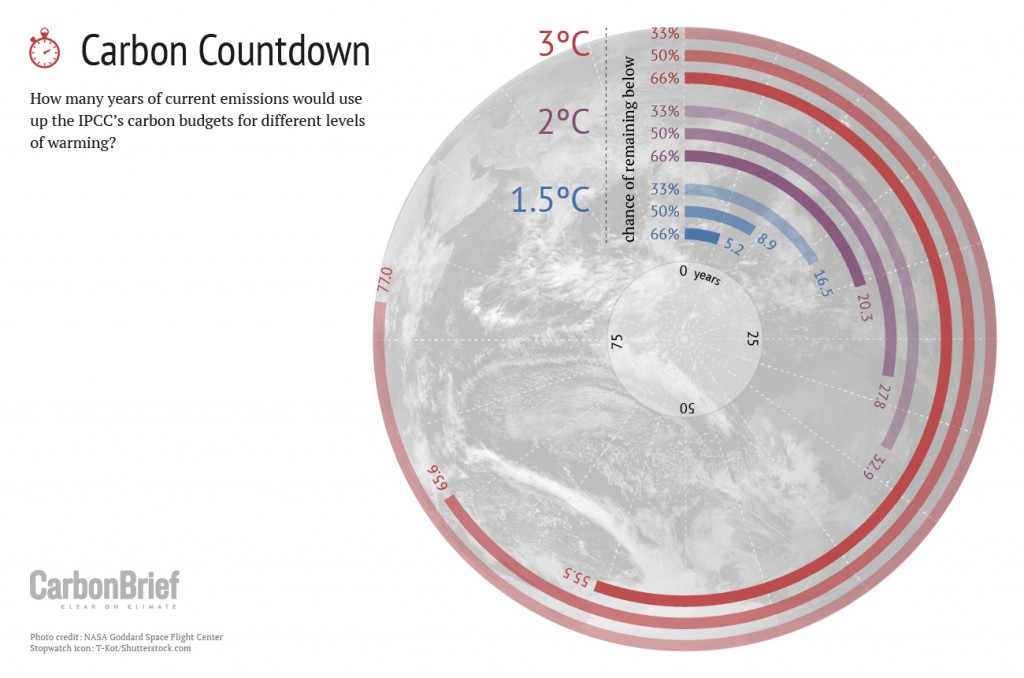

A trillion tonnes of CO2 is the same as the IPCC estimated was left in the carbon budget for a likely chance of staying below 2C, as of 2011. In 2016, five years worth of emission further on, that remaining budget has shrunk to around 800bn tonnes.

This means that using up the 2C budget would also mean the end of ice during the Arctic summer, says Notz.

Carbon Countdown: How many years of current emissions would use up the IPCC’s carbon budgets for different levels of warming? Infographic by Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief.

The study illustrates a “very powerful way” to talk about carbon emissions, says Dr Alexandra Jahn, a fellow at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado, who wasn’t involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief:

The relationship does appear to hold true in computer simulations of the future, says Notz. But sea ice is one of the most complicated elements of the climate system, notes Prof Andrew Shepherd, professor of earth observation at the University of Leeds, who wasn’t involved in the study.

This means that it’s probably more accurate to base projections on a physical understanding of the processes, rather than a simple historical relationship, he tells Carbon Brief:

Country contributions

![]()

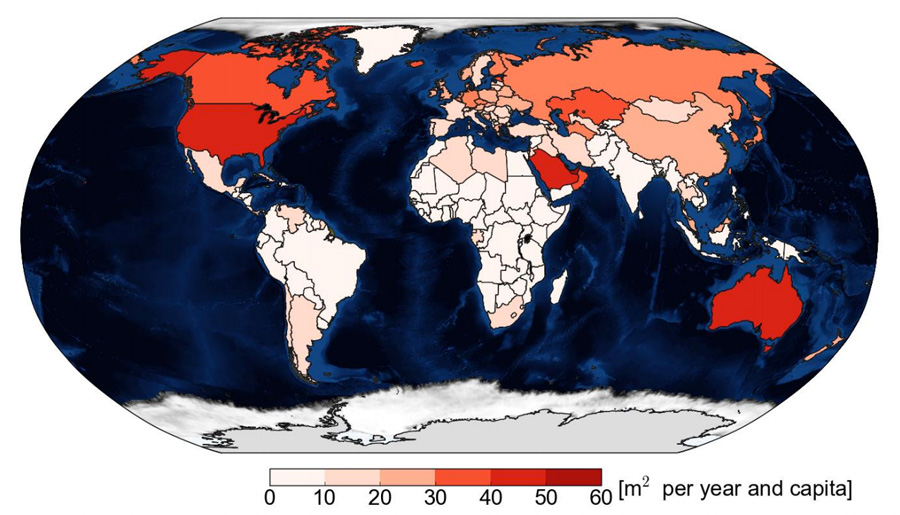

The authors also use the relationship between CO2 emissions and ice loss to suggest how individual countries are contributing to the decline of Arctic summer sea ice through their emissions.

Factoring in countries’ populations, the authors go as far as expressing this responsibility per person. For example, they work out that based on 2013 per capita emissions, each person in the US will contribute about 50 square metres of future Arctic sea ice loss. The same is true for people in Australia and Saudi Arabia. You can see these countries shaded red in the map below.

The country with the biggest per capita contribution is Qatar, whose 2013 emissions amount to almost 120 square metres of sea ice melt per person – that’s about the size of two squash courts.

In contrast, the emissions in much of Africa and South America in 2013 are likely to contribute less than 10 square metres of ice loss per person, according to the study.

Annual average loss of Arctic September sea ice extent as a result of per capita emissions in 2013, by country. Source: Notz & Stroeve (2016)

Bringing these figures right up to date, emissions in 2015 for the UK as a whole are enough to cause around 1,500 square kilometres of summer Arctic sea ice loss – that’s the size of Greater London.

And for the world, global emissions in 2015 will melt 160,000 square kilometres of ice, which is an area larger than Bangladesh.

It’s worth remembering here that this approach only accounts for CO2 emissions from fossil fuel burning and cement manufacture. So emissions of other greenhouse gases, and from land use change, aren’t included. An equivalent map including deforestation would show a much higher contribution from places like Brazil and Indonesia, for example.

Similarly, the map would also look quite different were it to include emissions from past years going back over the industrial period, not just emissions in 2013. Nevertheless, the study highlights how much Arctic sea ice melt can be prevented by cutting emissions, says Jahn:

Notz, D. and Stroeve, J. (2016) Observed Arctic sea-ice loss directly follows anthropogenic CO2 emission, Science, doi:10.1126/science.aag2345