Arctic sea ice winter peak in 2025 is smallest in 47-year record

Ayesha Tandon

03.28.25Ayesha Tandon

28.03.2025 | 2:30pmArctic sea ice has recorded its smallest winter peak extent since satellite records began 47 years ago, new data reveals.

Provisional data from the US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) shows that Arctic sea ice reached a winter maximum extent of 14.33m square kilometres (km2) last week.

This is 1.31m km2 below the 1981-2010 average maximum and 800,000km2 smaller than the previous low recorded in 2017, according to the data.

Dr Julienne Stroeve, a senior scientist at the NSIDC, tells Carbon Brief that such a small winter peak “doesn’t mean a record-low” summer minimum will necessarily follow in September.

But, she adds, it does “continue the overall long-term decline in the ice cover”.

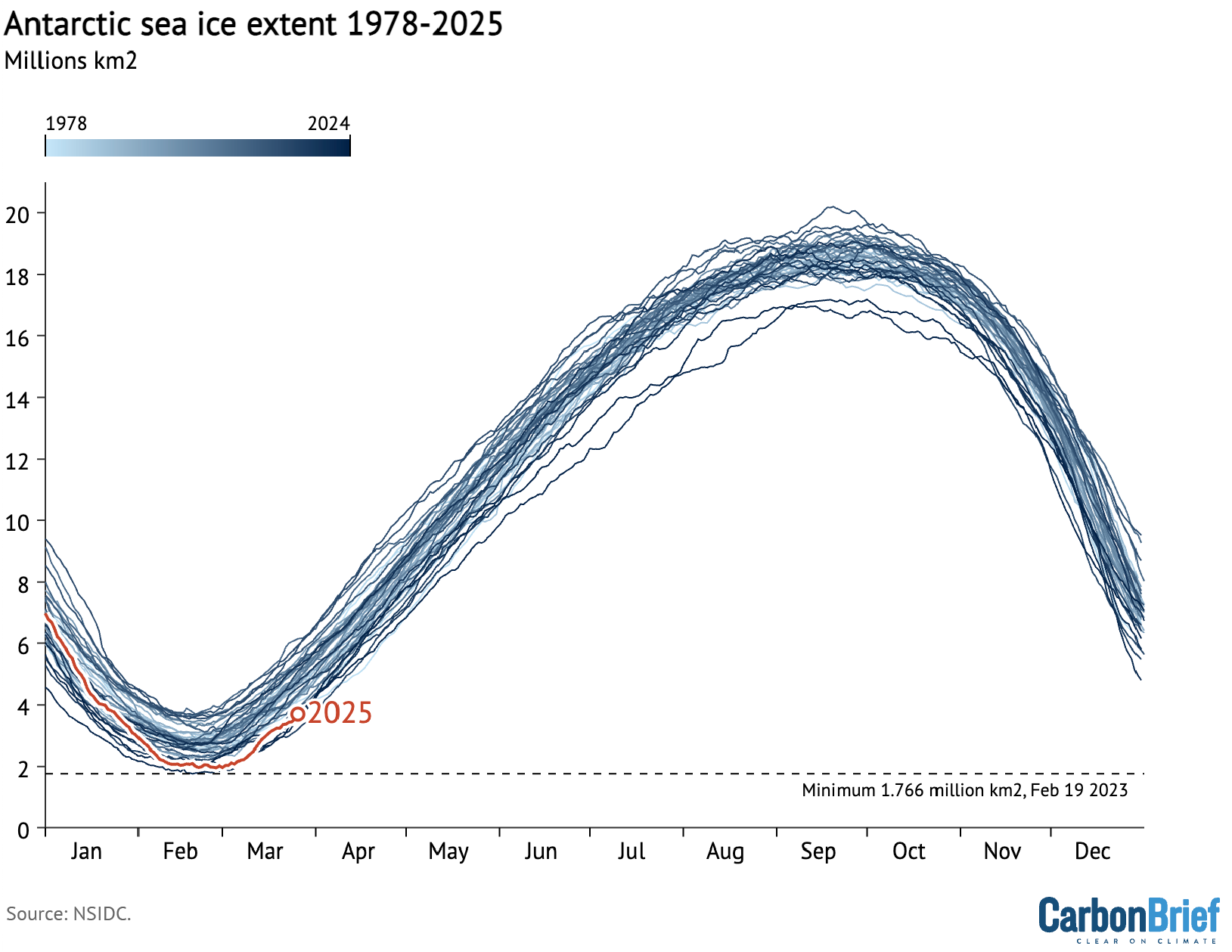

Meanwhile, Antarctic sea ice reached its summer minimum extent earlier this month, with 2025 tying with 2022 and 2024 for the second-smallest summer low on record, the NSIDC says.

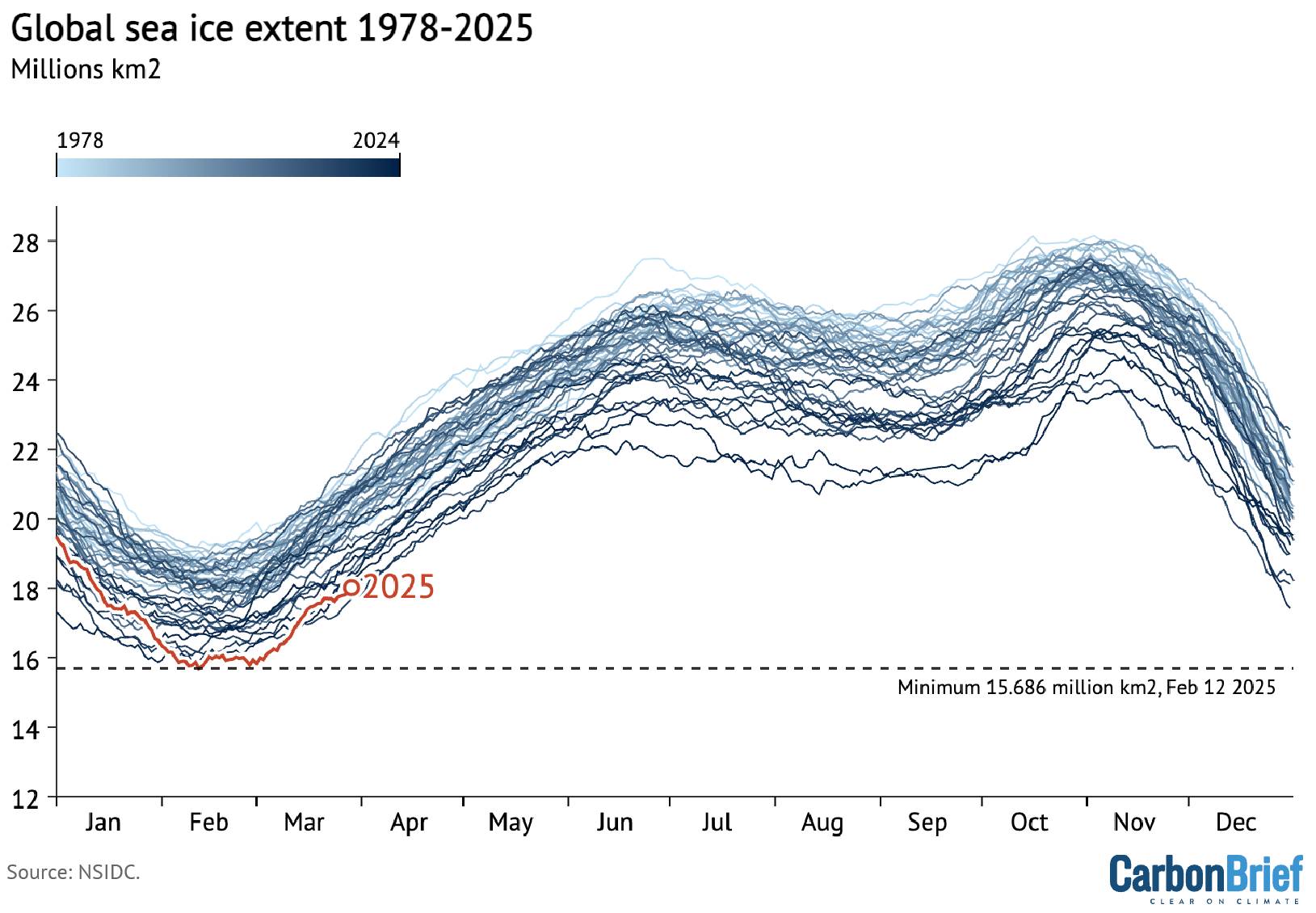

The combination of reduced sea ice cover in both the Arctic and Antarctic means that global sea ice extent dwindled to an “all-time minimum” in February this year, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S).

Record low

Arctic sea ice extent changes throughout the year. It grows during the winter towards its annual maximum extent – often referred to as its “winter peak” – in February or March. It then melts throughout the spring and summer towards its September minimum.

Using satellite data, scientists can track the growth and melt of sea ice, allowing them to determine the size of the ice sheet’s winter maximum extent. This is a key way to monitor the “health” of the Arctic sea ice.

On 22 March 2025, Arctic sea ice reached its smallest-ever winter peak, according to the NSIDC. At 14.33m km2, this was 1.31m km2 below the 1981-2010 average maximum and 800,000km2 below the previous low, which was recorded in 2017.

The chart below shows Arctic sea ice extent over the satellite era (1978 to the present day). Red indicates the 2025 extent, while shades of blue indicate different years over 1978-2024.

NSIDC senior research scientist Dr Walt Meier told the Press Association:

“This new record low is yet another indicator of how Arctic sea ice has fundamentally changed from earlier decades. But, even more importantly than the record low, is that this year adds yet another data point to the continuing long-term loss of Arctic sea ice in all seasons.”

Freeze season

The growth season for Arctic sea ice kicked off after reaching its summer minimum extent of 4.28m km2 on 11 September last year. This was the Arctic’s seventh-lowest summer low on record.

As temperatures cooled, the NSIDC says that Arctic sea ice grew slowly at the start of October. Ice growth then sped up towards the middle of the month and then slowed again towards its end. The average sea ice extent for October was 5.94m km2 – the fourth lowest on record, according to the NSIDC.

Throughout November, air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean were “mixed”, according to the NSIDC. It says that temperatures were above average from coastal Canada to northern Scandinavia, as well as in the area north of Greenland, but below average over the Beaufort, Bering and Laptev Seas.

Arctic sea ice grew at a steady pace for most of November – mainly in the Kara, Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, as well as Baffin Bay and the Canadian Arctic archipelago. However, in the Hudson Bay – where air temperatures were 1-5C above average – “no appreciable sea ice” formed, according to the NSIDC.

The November extent averaged 9.11m km2, ranking the third lowest in the satellite record and 1.59mkm2 below the 1981-2010 average, the NSIDC says.

December saw above-average air temperatures over “essentially all of the Arctic Ocean”, with a particularly “prominent” area of warmth off the Canadian Arctic archipelago and Greenland, the NSIDC says.

Due to delayed ice growth in the Hudson Bay and low extent in the northern Barents Sea, December Arctic sea ice extent was the lowest in the satellite record at 11.43m km2.

Daily Arctic sea ice extent decreased sharply at the end of January, when the region lost about 0.3m km2 – an area roughly the size of Italy – in less than a week, according to C3S.

It adds that “such a rapid decrease is unusual at this time of year, when sea ice is typically expanding towards its annual maximum”. It points to the “pronounced warm event” over the Greenland Sea and Svalbard region as the reason for the drop.

Dr Rick Thoman – a specialist in the Alaskan climate from the University of Alaska Fairbanks – tells Carbon Brief that the sea ice decrease in late January and early February was partially driven by “separate cyclones producing simultaneous south winds across much of the Barents and Bering Seas”. As winds pushed the ice northwards, “ocean wave action” melted the thin ice at the edge of the ice sheet, he says.

February was marked by slow Arctic sea ice growth, resulting in a record-low February Arctic sea ice extent of 13.75m km2, according to the NSIDC. The organisation adds that daily sea ice growth “stalled” twice in the month, which “helped to contribute to low ice conditions and led to overall ice retreat in the Barents Sea”.

This rapid melt was partially driven by above-average temperatures. Between northern Greenland and the north pole, temperatures reached up to 12C above average, the NSIDC says.

Antarctic melt

At the south pole, Antarctic sea ice has been declining during the southern hemisphere summer. It reached its annual minimum of 1.98m km2 on 1 March.

This summer low ties with 2022 and 2024 for the second-smallest Antarctic extent in the 47-year satellite record, the NSIDC says. It adds that the past four years are the only years on record in which Antarctic sea ice has reached a minimum below 2m km2.

The graphic below shows Antarctic sea ice extent over the satellite era. Red indicates the 2025 extent and shades of blue indicate different years over 1978-2023.

The melt season for Antarctic sea ice began with its winter maximum of 17.2m km2 on 19 September 2024.

This was 1.6m km2 smaller than the 1981-2010 average maximum and the second-lowest winter peak on record, according to the NSIDC.

As the southern hemisphere warmed, Antarctic sea ice began to melt. Throughout October, Antarctic sea ice extent continued to rank the second lowest on the satellite record following the record-breaking 2023 season, the NSIDC says.

It adds that “seasonal ice loss was relatively slow during the early part of the month, but the pace picked up substantially during the last week of October, approaching 2023 values”.

By 30 November, Antarctic sea ice was the third lowest on record, tracking higher than the 2023 and 2016 levels for the same date, the NSIDC says.

After a “prolonged period of record to near-record daily lows set in 2023 and 2024”, December 2024 saw Antarctic sea ice loss slow down, with the average rate of decline tracking “well below average”.

By the end of December 2025, Antarctic sea ice extent was roughly in line with the 1981-2010 average, according to the NSIDC.

As a result, it says that “speculation that the Antarctic had entered a new regime of strongly reduced Antarctic sea ice related to oceanic influences, has, at least temporarily, come to an end”.

It adds that sea ice extent was “above average over the western Weddell and Amundsen Seas and slightly below average in the Ross Sea, with near-average extents in other areas”.

Throughout February, Antarctic sea ice continued to melt – especially in the eastern Ross Sea and Amunsden sea, where ice concentration is low, according to the NSIDC.

Global ‘all-time minimum’

With sea ice at or around record lows in both the Arctic and Antarctic, global sea ice extent dropped to an “all-time minimum” in February this year, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S).

Global sea ice hit a new daily low in early February and remained below the previous record from 2023 for the rest of the month, C3S says.

The graphic below shows global sea ice extent over 1978-2025, where red indicates the 2025 extent and shades of blue indicate different years.

C3S deputy director Dr Samantha Burgess noted that the low sea ice came as “February 2025 continues the streak of record or near-record temperatures observed throughout the last two years”. She added:

“One of the consequences of a warmer world is melting sea ice – and the record or near-record low sea ice cover at both poles has pushed global sea ice cover to an all-time minimum.”

The story was picked up in newspapers around the world, including the Guardian, Hindustan Times and Washington Post.

In response to the news from C3DS, Prof Richard Allan – a professor of climate science at the University of Reading – warned that “the long-term prognosis for Arctic sea ice is grim”. He added:

“Averaging over all regions the global warming trend is clear, with February 2025 more than 1.5C above pre-industrial conditions, repeating a level of excess warmth experienced in all but one of the past 20 months despite a weak cooling influence of La Niña conditions in the Pacific.”