Simon Evans

17.10.2014 | 12:45pmAn ambitious EU 2030 climate framework could be crucial to unlocking a global climate deal in Paris next year. Yet EU leaders still can’t agree the details, with just days to go.

Uncertainty remains because different EU member states want different things from the 2030 framework, which will set the trajectory for EU climate and energy policy for the next 15 years. Some countries want three targets – to cut emissions, increase use of renewable energy and boost take up of energy efficiency. Others want an emissions target only. And a few say they will only accept targets with sweeteners.

So who wants what from the EU 2030 climate and energy framework, and what does that mean for how ambitious it will be?

Emissions target

The EU’s 2030 climate and energy policy framework is due to be hammered out in outline by heads of government at the European Council summit next Thursday. A leaked draft of conclusions for the meeting seen by Carbon Brief shows consensus forming around a binding emissions cut of 40 per cent of 1990 levels by 2030. The draft also points to a 27 per cent target for Europe’s share of renewable energy and a 30 per cent cut in energy use compared to business as usual.

For the wider world the emissions target is the most important. The EU likes to see itself as a climate leader that is lighting the way to a low carbon future. Indeed, UK climate and energy secretary Ed Davey said this week:

“We need this deal so that so Europe can continue to lead the world to a global climate change deal in Paris next year.”

A 40 per cent emissions reduction should be the minimum level of ambition according to 22 out of the EU’s 28 member states, shown in shades of green on the map below.

EU member states are shaded according to the 2030 emissions reduction they favour. The [square brackets] for countries shaded red indicates they have not agreed to the 40 per cent figure. Source: various; map by Carbon Brief

A 40 per cent reduction by 2030 would be a milestone towards the EU’s long-term objective of an 80 to 95 per cent cut in emissions by 2050, European Commission president José Manuel Barroso told last month’s New York climate summit, saying: “In effect, we are in the process of de-carbonising Europe’s economy.”

This is the EU pitch to the rest of the world in the run up to Paris: we’re doing our bit, now play your part.

But not everyone is convinced that 40 per cent is ambitious. Consultancy Ecofys says it would leave the EU behind the curve against its 2050 goal, meaning accelerated efforts after 2030 would be needed to get back on track.

That’s why some like the UK’s David Cameron, Germany and Sweden , have been calling for a reduction of “at least” 40 per cent (shaded darker green on the map above). They want to go to the Paris climate talks offering to increase ambition, if other countries play along.

Poland is leading opposition to an ambitious 2030 deal over fears of increases in its energy costs and damage to its domestic coal industry. It was the only member state to explicitly oppose an emissions target during a commission consultation last year.

It has been trying to present a united front with the so-called Visegrad+ group of eastern European countries, including Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Croatia. However, this alliance is falling apart, with some countries shifting from red to green on the map above in recent weeks by signalling support for a 40 per cent goal.

The Czechs are now expected to back three 2030 targets, for example. Croatia did not sign up to the latest Visegrad+ statement on the 2030 targets and is also backing a 40 per cent emissions goal.

So Poland is now seen as the only serious block to the overall 2030 agreement. In her inaugural address to the Polish parliament in September, new prime minister Ewa Kopacz said she would oppose a deal that would raise energy prices. Poland is reported to have estimated that a 40 per cent emissions reduction target would cause a 120 per cent increase in power sector prices.

News reports have painted Poland as ” on course for a battle with Brussels“. It continues to brief journalists that it might veto the framework without further concessions. However, it is also said to be “working in the spirit of not blocking an agreement”.

In effect, Poland is trying to use the threat of a veto to extract concessions that will make it easier to comply with the 2030 targets and allow it to tell its domestic audience that its coal industry will be protected. Sources suggest it will ultimately not oppose a 40 per cent goal as long as it gets other sweeteners.

The chance of a Polish veto is thought to have been reduced by the appointment of incoming European Council president and former Polish prime minister Donald Tusk, who would have to pick up the pieces if the 2030 framework fails.

Renewable energy target

The next piece in the puzzle is the commission’s proposed goal to get at least 27 per cent of energy from renewable sources by 2030. This is less likely to make or break the deal and has broader support than the 40 per cent emissions goal, as the map below shows.

EU member states are shaded according to their favoured renewable energy target. The [square brackets] for countries shaded red indicates they have not agreed to the 27 per cent figure. Source: various; map by Carbon Brief

The big question for the renewable target is how binding it will be. The UK initially opposed a binding renewables target, favouring a “technology neutral” single emissions goal. But it now backs 27 per cent as long as it is only binding at EU level, not on member states.

A binding target is important for Germany’s plans to continue increasing its renewables share, leading some to suggest the UK concession on a renewables target was the price for German support for plans to build a new nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset.

The effectiveness and enforceability of a target only binding at EU level has been widely questioned, including by the International Energy Agency. It would depend on as yet undeveloped governance mechanisms.

The commission is confident that member states are on track to exceed the planned 27 per cent target. Nevertheless it’s unlikely this target will be binding at member state level: only Austria backs such a move.

Energy efficiency target

The mooted 30 per cent energy efficiency target is set to be “indicative”. That means it won’t be binding at either EU or member state level. The measure has faced a battle to even make it this far, with parts of the commission backing lower 25 or 27 per cent targets.

Seven member states that publicly backed a binding energy efficiency target in a June letter have now been joined by France. But the internal commission wrangling is reflected in the map below, with much wider disagreement over efficiency than over the other 2030 targets.

EU member states are shaded according to their favoured energy saving target. Again, square brackets indicate lack of agreement to any specific target. Source: various; map by Carbon Brief

The UK has long opposed any energy saving goal, leaving it out of step with its usual geographical allies in the EU. Reuters reports that the UK is still “uncomfortable” with the idea, but could live with an EU-wide goal.

This discomfort is thought to come from the highest levels of government, with David Cameron wary of approving a new EU target in the face of the political threat from the UK Independence Party and recent controversy over vacuum cleaner efficiency rules.

But climate secretary Ed Davey said this week that the UK may be willing to compromise and that there were “no red lines” over the issue. He has also said there will be no UK veto.

Continued opposition from central and eastern states leaves the efficiency target at risk of being weakened and reduces the chance it will be made binding. However, incoming commission president Jean-Claude Juncker has said a binding 30 per cent goal is his minimum.

How ambitious will the 2030 framework be?

Last time around during negotiations for the EU’s 2020 deal, Poland and others were very successful in extracting concessions including free emissions allowances for their power sectors.

These concessions made the 2020 target much easier to hit and, combined with the 2008 financial crisis, mean over-achievement has built up in the system. Emissions have been cut by more than was needed.

How ambitious the 2030 framework is therefore depends heavily how this overachievement is treated, and on how future help for poorer member states is designed.

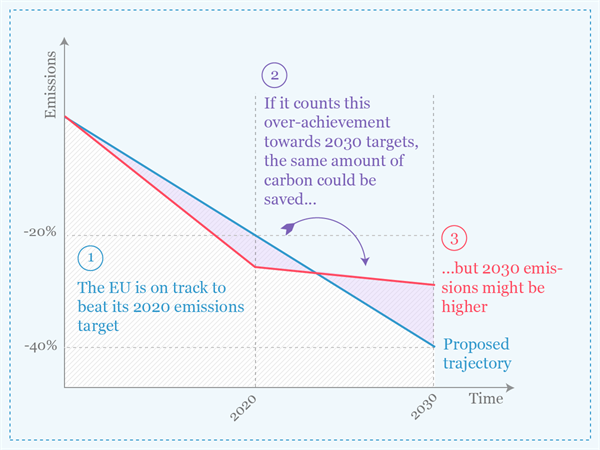

To see why this matters let’s look at the EU’s planned emissions-cutting trajectory. The EU is currently ahead of the curve and is expected to beat its targeted 20 per cent reduction for 2020. This means it is building up a surplus of over-achievement in the formed of “banked” emissions allowances, represented in the left-hand lilac shaded area on the schematic below.

Schematic by Carbon Brief. Not to scale.

NGO Carbon Market Watch says the over-achievement amounts to 2.6 billion tonnes within the EU’s emissions trading scheme (EUETS) and a further 1.35 billion tonnes in sectors outside the ETS. They think that if all of this surplus is carried forward (the right-hand lilac area) it would turn the 40 reduction on 1990 levels into a 26 per cent reduction.

Horse-trading over planned EUETS reform that could eliminate some of this surplus, and over whether banked non-ETS allowances can be carried forwards, will form an important part of discussions next week. There will also be arguments over a planned goal to boost electricity grid interconnection around the EU, with opposition led by France.

The other key area of negotiation is about funds that will help poorer EU member states meet 2030 targets through power sector decarbonisation and energy efficiency. Free allocation of allowances to their power sectors under the 2020 deal was supposed to have already kickstarted this process, but instead ended up mostly going to prop up the Polish and Romanian coal industries.

Poland wants funds to flow in the same way, with no strings attached. The UK, France and Germany are desperate to avoid this, as it could see coal use persist in Poland out to the 2070s and beyond.

They want 2030 modernisation funds to be managed by the European Investment Bank because it has an emissions performance standard that heavily restricts investment in coal. But until they settle their disagreements over energy efficiency and interconnection their joint negotiating position is weakened.

In the end it looks like some form of triple 2030 target will be agreed next week, including a 40 per cent emissions reduction. But there is still plenty of wiggle room that could make any headline figures much less ambitious than they first appear.

Update 15.25: It’s worth noting that the European Council has no legislative powers. Heads of state meeting next week will try to agree on the 2030 targets but cannot make new laws. Instead, they set the policy framework for future EU rules. The European Commission, Parliament and Council of Ministers would have to draw up and agree on any new EU legislation.

Update 20/10: We amended the language because this is a 2030 policy "framework" that will set the parameters for future policy but is not a "package" of proposed legislation.