Analysis: UK auction reveals offshore wind cheaper than new gas

Simon Evans

09.11.17Simon Evans

11.09.2017 | 5:12pmThe UK government today awarded contracts worth £176m to 11 low-carbon electricity schemes, with offshore wind the big winner. These projects will generate nearly 3% of UK electricity demand.

Two offshore wind schemes won contracts at record-lows of £57.50 per megawatt hour (MWh). This puts them among the cheapest new sources of electricity generation in the UK, joining onshore wind and solar, with all three cheaper than new gas, according to government projections.

The offshore wind schemes are also close to being subsidy-free: the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) expects wholesale power prices to average £53/MWh in the period from 2023 to 2035, covering the bulk of their 15-year contract period.

The auction results shift the conversation, from renewables being expensive, towards how cheap, variable zero-carbon power can be integrated into the grid, while maintaining sufficient supplies of power throughout the year.

Offshore wind results

Today’s auction is the second competitive auction and third award of contracts for difference (CfDs). These are contracts at a fixed “strike price” and most of them last for 15 years. During the contract period, projects are paid the difference between a reference wholesale price and their strike price. If wholesale prices rise above the strike price, the project pays back the difference.![]()

This guaranteed income allows developers to get more favourable terms from investors. This cuts the cost of borrowing, which makes up a large part of the total price tag for low-carbon generation.

In the first round, in 2014, the government awarded 15-year CfDs to five offshore windfarms at £140-150/MWh. These projects are coming online during 2017 and 2018. These awards were criticised by the National Audit Office, which said competitive auctions could have cut costs.

In the first CfD auction, held in 2015, contracts worth £315m were awarded to 27 schemes, with a total capacity of 2.1 gigawatts (GW). The majority of this was offshore wind, at prices of £120/MWh for projects coming online in 2017/18 and £114/MWh for 2018/19. Onshore wind and solar schemes supported in this first auction came in at around £80/MWh.

Today’s second CfD auction awarded £176m to 11 schemes totalling 3.3GW, of which three offshore wind projects made up 3.2GW. The 860 megawatt (MW) Triton Knoll windfarm off Lincolnshire is due to come online in 2021/22 at a cost of £74.75/MWh.

The following year, the 950MW Moray Offshore Windfarm (East) and 1,360MW Hornsea 2 scheme will come online at a cost of £57.50. The total 3.2GW will cost an average of £64/MWh.

These offshore wind schemes will be phased, meaning only parts of their capacities will start generating power during the first year. This is expected to allow developers to take advantage of falling technology costs and the hoped-for availability of larger, more cost-effective turbines.

If a 35m offshore wind turbine can generate 0.45MW…

…and a 120m turbine 3.6MW…

How big would a 15MW turbine be? My guess is around 230m! pic.twitter.com/e4aBvMsbls

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) April 20, 2017

A number of small incinerators and biomass combined-heat-and-power plants were also awarded CfDs today at prices of between £40 and £75/MWh. Their total capacity is 150MW, the maximum allowed under auction rules set by BEIS.

The lower-than-expected prices in today’s auction mean BEIS was able to support 3.3GW of capacity despite only allocating £176m out of the £295m total it had available.

Additional bids might have been too high or too large: The remaining money could have supported an extra 3GW of offshore wind at £57.50/MWh, or just 190MW at £70/MWh.

The government had previously promised to run three rounds of auctions, including today’s, with up to £760m available. It has yet to confirm if additional auctions will take place.

Cheaper than gas

This illustrates the most striking thing about the CfD auction results so far: wind and solar have consistently delivered far lower prices than expected. Indeed, BEIS had set a price target for offshore wind of £85/MWh in 2026, far higher than the contracts awarded today.

In late 2016, BEIS projections suggested offshore wind projects coming online in 2025 would cost around £100/MWh – far more than new gas and comparable with new nuclear. At the time, BEIS said onshore wind and large solar farms would be the cheapest new power sources.

(Note that BEIS has so far refused to run so-called pot 1 CfD auctions for onshore wind, solar and other “established” technologies. However, the 2017 Conservative manifesto left the door open to offering support for onshore wind outside England.)

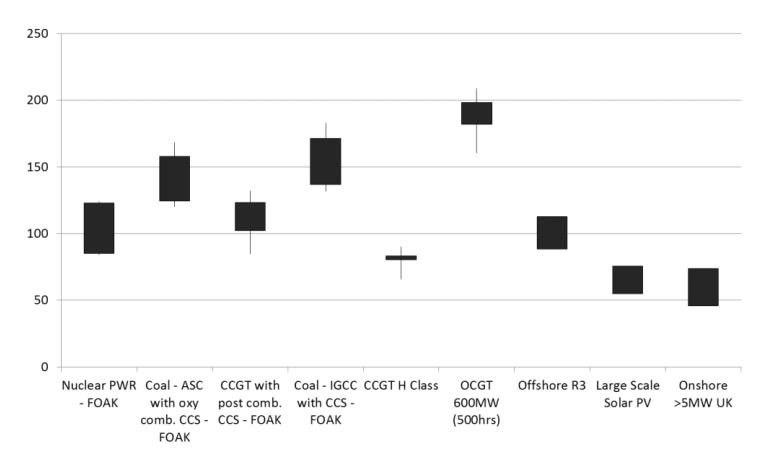

Levelised costs of electricity generating capacity coming online in 2025. PWR FOAK is first-of-a-kind pressurised water nuclear reactors. CCS is carbon capture and storage. CCGT is combined cycle gas turbine. OCGT is open cycle gas turbine (for peaking). R3 is the third round of offshore wind licences awarded by the Crown Estate. Source: BEIS projections.

Today’s auction has destroyed the 2016 BEIS projections, with offshore wind projects again coming in far cheaper than expected.

The chart below shows awarded CfD prices for wind and solar (blue and yellow lines) compared to the Hinkley C new nuclear plant (purple line), which has a 35-year CfD for £92.50/MWh. Also shown are current and expected wholesale power prices (black) and the projected cost of building large new gas-fired combined cycle plants (CCGTs, red).

Costs of UK electricity generation, £/MWh. Wholesale prices are actual (solid black line) and projected, (dashed line). Technology costs reflect awarded contracts and projections, see notes below for more details. Sources: BEIS projections, CfD auction results and Baringa Partners. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.The chart shows that offshore wind, along with onshore wind and large solar farms, are all thought to be cheaper than new gas generation (see notes below for more on this comparison, which includes a rising carbon price reaching £49 per tonne by 2030).

By the mid-2020s, renewables will be cheaper than new gas even after accounting for the costs of integrating them into the electricity grid and providing backup to guarantee supplies.

Writing before today’s auction results, Gareth Miller, chief executive of consultants Cornwall Energy, wrote: “The traditional challenge [that] critics of onshore renewables have posed about whole system costs eradicating the competitive benefits of deployment start to disintegrate at these sorts of strike price levels.”

The best available estimates suggest these so-called whole-system costs will add around £10-15/MWh. This includes balancing unexpected short-term fluctuations in output and providing back-up capacity for cold, dark and still days in winter when renewable generation is low.

(Note that windfarms in the UK generate power almost all of the time, whereas their output varies. For example, offshore wind generated close to 100% of hours during November 2016. BEIS expects new offshore windfarms to have a load factor of close to 50%.)![]()

System costs are expected rise to between £15 and £45/MWh if wind and solar supply half the UK’s power, up from 15% in 2016. The top end of this range reflects a very inflexible electricity grid. Costs would be at the lower end, if the government’s plans to encourage a flexible grid bear fruit.

Subsidy free?

The chart above shows renewables are also close to becoming subsidy-free, with prices approaching expected future wholesale costs. (Note this is before accounting for integration costs). For example, today’s £57.50/MWh offshore wind contracts are less than £5/MWh above the £53/MWh average wholesale price projected by BEIS for 2023-2035.

However, these contracts fall short of results in Germany, where Dong Energy has won the right to build offshore wind projects without subsidy. This subsidy-free price excludes some of the costs of connecting to the grid, which are included in the UK contracts.

This handy graphic from @DONGEnergyUK explains why offshore wind prices vary in UK vs DE vs DK/NL – it’s about who pays for grid / cables pic.twitter.com/pYw9QA8LPT

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) May 10, 2017

As well as grid connection costs, contracts in Germany and the Netherlands can exclude site scoping and design, with developers competing to build already agreed projects. See this June 2017 Offshore Wind Journal article for more on how the UK system compares.

Conversation changer

Today’s auction is likely to challenge preconceptions about renewable power. For example, Prof Dieter Helm, who is leading a government review on costs of energy, has said offshore windfarms will “never” be economic.

It might also increase pressure on the government to run auctions for onshore wind and solar, which are likely to be even cheaper. Consultants Baringa Partners say auctions could secure 1GW of onshore wind for £46/MWh, which would be effectively subsidy-free. Meanwhile, Cornwall Energy says some onshore schemes could offer CfD bids as low as £40/MWh.

Securing subsidy-free renewables would help fill the gap in electricity supplies, which is expected to open up in the 2020s as the UK’s remaining coal plants close, old nuclear retires and more stringent carbon targets start to bite.

(This gap will be even wider if electric vehicles raise demand, though this is unlikely to be significant during the next decade. It could be shrunk if the UK implements cost-effective energy efficiency policies that could cut household demand by a quarter).

On the other hand, despite rapidly falling prices, the UK must face the challenge of managing the variable output of wind and solar and integrating them into the electricity grid. Here, the government’s plans to encourage a more flexible grid will be key to keeping costs to a minimum.

Today’s results do not necessarily mean the UK can focus on renewables alone. The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) argues for a portfolio of technologies in order to keep options open for meeting long-term carbon targets. All of its pathways for the fifth carbon budget include renewables and at least one of either new nuclear power or carbon capture and storage.

Notes on the chart

The chart of electricity generation costs amalgamates several different sources of information. As noted below, these are not all strictly comparable. Nevertheless, the chart is indicative of the trends at play in the UK power market.

The wholesale power price is from the ICIS power index for past and current prices, with the 2017 figure a year-to-date average. Future power prices are central BEIS projections, published in 2017, amended for 2022 through 2025 with numbers published as part of today’s auction. Note that the latter are references prices, which are not strictly the same as wholesale prices.

The technology costs are shown in 2012 prices and include BEIS projections, awarded contracts and other estimates.

For nuclear, the strike price for Hinkley C is shown. Note that this is a 35-year contract, which spreads the cost over more years and hence depresses the price compared to the 15-year contracts for renewables.

On the other hand, strike prices tend to be inflated relative to the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE), shown for some of the technologies, which spreads the cost over the lifetime of each project.

(Update 12/9/17: The offshore wind strike prices of £74.75 and £57.50/MWh are equivalent to LCOEs of £65 and £51/MWh respectively, according to the Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult, a government-backed research and innovation centre.)

For offshore wind, the prices shown reflect already awarded contracts for each delivery year, with a straight line drawn in between years. For onshore wind, contract prices are shown for 2017, BEIS LCOE projections for 2018 and 2020, then an estimate from consultants Baringa Partners for 2022.

The solar line includes contracts awarded in the first CfD auction and then BEIS projections, which are likely to be an overestimate of the true costs.

For gas, the line shows BEIS projections. Note that this includes a rising price for wholesale gas and, more importantly, a rising carbon price that reaches £49 per tonne in 2030. It could be argued that this overstates the cost of gas generation. However, this rising price remains below one that would be consistent with meeting the UK’s legally-binding carbon budgets. An argument against including any carbon price amounts to an argument against meeting UK climate goals.

The LCOE and strike prices are good for comparing the costs of generating an additional megawatt hour of electricity. However, they are relatively poor metrics for comparing the cost and value of meeting all the needs of the electricity system.