Do you know your Bali Action Plan from your Kyoto Protocol? Thousands of politicians, diplomats, and NGOs are currently meeting in Lima, Peru, as part of an international process to agree a global response to climate change.

The negotiations are now more than 20 years old, and have developed a language all of their own. Here’s our guide to the key terms.

Bali road map

Agreed at the Bali meeting in 2007, this was countries’ first effort to lay the foundations for a new global deal to replace the Kyoto protocol, which expired in 2012. The road map contained the Bali action plan, which outlined options for progress on climate mitigation, adaptation, technology and finance.

The UNFCCC now acknowledges that the Bali action plan “may have been overly optimistic, and underestimated the complexity both of climate change as a problem and of crafting a global response to it.”

Cancun Agreements

After the disappointment of Copenhagen, negotiators expectations for 2010’s meeting in Cancun were much lower. That meeting’s conclusions were captured in the Cancun Agreements, which were mainly notable for formally committing countries to preventing temperatures rising by more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels, more than three decades after the limit was first proposed.

Copenhagen Accord

The much-hyped Copenhagen climate talks in 2009 were meant to deliver a new legally binding, global deal to replace the Kyoto protocol. Instead, they resulted in a “political agreement” called the Copenhagen Accord. The accord “recognised” the need for countries to tackle climate change, and set the deadline to review existing agreements by the end of 2015.

The Copenhagen climate conference in 2009. Credit: UN Photos

Doha Climate Gateway

The Doha meeting in 2012 wasn’t particularly notable, and nor was the Doha Climate Gateway that negotiators agreed at the meeting. The most high-profile part of the deal was that policymakers agreed to look into the issue of compensating countries for loss and damage caused by climate change.

Durban Platform

At a meeting in Durban in 2011, countries agreed the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. It extended the Kyoto protocol until at least 2017 and committed countries to agreeing a new global deal by the end of 2015.

Carbon neutrality

There are two ways the world could become carbon neutral. It could stop emitting carbon dioxide through processes like burning fossil fuels for power or running petrol cars. Or, perhaps more likely, it could keep doing a bit of this while also capturing carbon dioxide and locking it away using carbon capture and storage technology. This means the world would have net zero emissions, even if countries continue to emit some greenhouse gas.

Almost all of the scenarios the IPCC suggest where temperatures rise by less than two degrees rely on carbon capture and storage.

Common but differentiated responsibility

Developing countries often talk about ensuring any new global deal respects the principle of common but differentiated responsibility. This basically means designing a deal where those with the greatest historical responsibility for climate change and the means to implement low carbon policies take the biggest and earliest steps to cut emissions.

This principle was enshrined in the UNFCCC, which separated countries into three groups: Annex I, Annex II, and non-Annex I.

Annex I countries agreed are industrialised countries that agreed to binding targets to cut emissions under the Kyoto Protocol. Annex II countries are a smaller group drawn from Annex I, with extra responsibilities for providing financial assistance to developing countries to tackle climate change. Non-Annex I countries are mainly developing nations that are not expected to make significant emissions cuts.

Conference of the Parties (COP)

The “supreme decision-making body” of the UNFCCC is the conference of the parties (COP), comprised of representatives for each of the nations that signed the convention. The COP meets once a year, with those meetings forming the focal point for international climate change negotiations. The meeting in Lima in 2014 was the 20th COP meeting (COP20). Next year’s meeting in Paris will be the 21st (COP21).

Country groups

Countries often negotiate as part of a bloc at the international talks. We’ve gone into detail about which issues each group is principally concerned with here, but these are a few acronyms you should know:

- AGN – African Group of Negotiators

- AILAC – Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean

- ALBA – Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America

- AOSIS – Alliance of Small Island States

- BASIC – Brazil, South Africa, India and China

- CACAM – Central Asia, Caucasus and Moldova

- EIG – Environmental Integrity Group

- LDC -Least Developed Countries

- LMDC – Like-Minded Developing Countries

- SICA – Central American Integration System

- SIDS – Small Island Developing States

- OPEC – Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

Draft text

This refers to the text of a new global deal to cut emissions and tackle climate change. The Lima meeting is expected to deliver a draft of the deal, with negotiators setting about ironing out the details over the next 12 months, as the Paris meeting looms into view.

A look inside the Copenhagen conference in 2009. Credit: UN Photos

Financial Mechanism, The

The UNFCCC and subsequent deals created a set of policies that transfer funds from rich countries to poorer nations to help them tackle climate change. The Financial Mechanism is the means of transferring these funds.

The Financial Mechanism houses four special funds. The Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) was created in 2001 to finance projects relating to adaptation, technology transfer, energy, transport, industry, agriculture, forestry and waste management. The Adaptation Fund (AF) was established in 2001 to finance adaptation programmes in developing countries. The Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) was established in 2002 to help the world’s poorest nations implement climate policies. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was established in 2009 and seeks to channel funds to developing countries to put them on lower carbon development pathways and adapt to climate change.

Global deal

In 1997, 193 countries signed the world’s first binding agreement to cut emissions: the Kyoto Protocol. That treaty is set to expire next year. Negotiators are busy trying to agree a deal to replace it that will, unlike the Kyoto protocol, include the world’s biggest emitters China and the US.

Green climate fund (GCF)

The GCF was established at the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009 with the aim of channeling money to help developing countries implement climate adaptation policies. When the fund is fully operational, nation states will contribute $100 billion a year. Countries have so far pledged a little over $10 billion to the fund for its first four years.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

The UN’s official climate science advisor, the IPCC produces major reviews summarising the state of climate research. Its fifth assessment report, also known as AR5, was completed in 2014.

The IPCC’s reports are split into three parts. Each instalment is the responsibility of a different set of researchers, known as a working group. Working group 1 (WG1) looks at the physical science of climate change. Working group 2 (WG2) assess the impacts of climate change, and how to adapt to them. Working group 3 (WG3) focus on climate policies to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Here’s a catalogue of our summaries, guides, and analyses of AR5.

Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs)

In 2013, countries agreed that governments would submit their own targets to cut emissions by the end of March 2015, known as INDCs. These submissions will then be reviewed, with countries negotiating over whether they need to be more or less ambitious.

The INDC approach represents a move away from a centralised target setting system established by the Kyoto Protocol, where the UNFCCC – with the COP’s assent – decided countries’ goals based on their historical emissions and ability to implement climate policies.

Kyoto protocol

In 1997, 193 countries signed the world’s first binding agreement to cut emissions: the Kyoto Protocol. The treaty set limits on countries’ emissions, taking into account their historical contribution to climate change and ability to implement policies, with the aim of cutting global emissions five per cent on 1990 levels by 2012.

The protocol was originally set to expire at the end of 2012. In 2010, countries extended the protocol into a second commitment period due to end in 2020.

The protocol was hamstrung from the start by the US’s refusal to participate. While US president Bill Clinton signed the treaty, it was never ratified by Congress. Creating a new deal to replace the Kyoto protocol that all the world’s major emitters will sign is a key part of the current international climate talks.

UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon meets Al Gore at the Copenhagen climate conference in 2009. Credit: UN Photos

Legally binding

One of the main points of contention in the negotiations is whether countries should be legally obligated to cut emissions under any new deal.

The EU is in favour of legally binding emissions reductions targets for all countries. The US is determined that any new deal should not be legally binding as it would then have to get the assent of the US Congress, which is extremely unlikely. Many countries, such as India, support legally binding targets for developed economies but would reject a deal that applied them to developing nations.

Loss and damage (L&D)

This phrase refers to the impacts of climate change that countries won’t be able to adapt to, and which will result in economic losses. Some countries are calling for a mechanism to be introduced where developed nations, that are historically responsible for the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions, compensate those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Market mechanisms

One approach to cutting emissions is to use the power of the market to discourage polluting activities and encourage low carbon investment. Market mechanisms supposedly allow countries to meet their emissions reduction targets in a flexible way.

Perhaps the UNFCCC’s best known market mechanism is the Clean Development Mechanism. This allows developed countries to fund low carbon projects in developing countries, such as building a new windfarm, and count any emissions reductions that ensue against their own goals.

The Kyoto protocol also created an international emissions trading system. Under the scheme, countries are allocated permits to emit greenhouse gases. Those that emit less than their allowance can then sell the permits to countries wanting to emit more.

Mitigation and adaptation

Climate policies have traditionally been divided into two strands: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation policies seek to cut emissions to curb climate change. Adaptation policies help countries deal with the impacts of climate change.

National Adaptation Plans (NAPs)

At the 2010 Cancun meeting, countries agreed the Cancun Adaptation Framework. As part of the framework, countries agreed to develop National Adaptation Plans to identify strategies and policies to protect them from the impacts of climate change. The least developed countries also formulate National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs), focusing on policies to reduce future risks by making countries more resilient to climate change now.

Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs)

The Bali Action Plan established that developing countries would take some action to curb emissions without sacrificing their economic development. Such policies are known as Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions.

Two degrees (2°C)

Limiting warming to no more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels has become the de facto target for global climate policy. The limit was first suggested in the 1970s but didn’t formally become the UNFCCC’s goal until 2010. There are now serious questions about whether the world can cut emissions enough to stay within the two degrees limit.

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD)

One strand of the talks focuses on cutting emissions from agriculture, forests, and other land uses (AFOLU), sometimes also referred to as land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF). AFOLU accounts for about 24 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

REDD policies are one aspect of that effort, aimed at reducing emission from chopping down trees. REDD+ includes conservation and sustainable forestry policies as well as those aimed at preventing deforestation. REDD++ has been proposed, and would include emissions reduced across the entire AFOLU spectrum.

Road to Paris

World leaders have set a deadline to agree a new global deal by the end of 2015 at a meeting in Paris. As a consequence, recent meetings have been conducted under the auspices of making as many small agreements as possible before then. Any progress is often referred to as progress on the ‘road to Paris’.

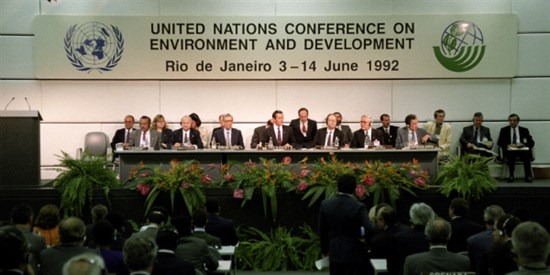

The Rio Earth Conference in 1992, where countries signed the UNFCCC. Credit: UN Photos

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

In 1992, world leaders signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Article 2 of the convention commits countries to stabilising “greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” The big annual climate talks, and some smaller meetings, are held as part of the UNFCCC process.

US-China deal

The US and China signed an historic deal to cut emissions in the run up to the Lima talks. It was the first time both of the world’s largest emitters had agreed to take action on climate change and changed the complexion of the negotiations. Instead of spending lots of time pressuring the US and China to agree, negotiators should now be able to turn their attention to hammering out the details of a new deal.

The agreement is the most prominent example of countries making bilateral deals on climate outside of the UNFCCC process.

Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage

The Warsaw climate conference in 2013 was perhaps most notable for being hosted by Poland, a country committed to promoting the coal industry. The meeting also established the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage, giving policymakers a formal structure within which to discuss compensating countries for the damage caused by climate change could sit.