Alaska refuge drilling could threaten polar bears with ‘lethal’ oil spills

Daisy Dunne

04.24.24Daisy Dunne

24.04.2024 | 10:44amFossil-fuel drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) could put polar bears at risk of “lethal” oil spills, new research suggests.

Former president Donald Trump passed a law to enable drilling in the refuge in 2017.

This followed decades of fierce debate between Democrats and Republicans about whether to allow extractive activities in the 7.7m-hectare (19m-acre) expanse, a haven for wildlife sitting on top of an estimated 11bn barrels of oil.

On his first day in office, US president Joe Biden suspended drilling inside the ANWR pending a review. In 2023, his administration cancelled the seven oil and gas licences issued for the reserve under Trump.

However, by law, the Biden administration is still required to hold a second lease sale for the ANWR by December 2024, unless Congress is able to pass legislation undoing the provision set out in Trump’s tax bill.

And with Trump pledging to “drill, baby, drill” if reelected to power later this year, a Republican victory in the next US election would likely see the refuge opened up for oil and gas extraction once again.

The new study, published in Biological Conservation, uses modelling to examine how a series of “worst-case scenario” oil spills could impact polar bears that use the refuge to raise young and feast on bowhead whale carcasses.

The research finds that a serious oil spill inside ANWR could expose up to 38 bears to lethal levels of oil and dozens more to harmful levels.

The risk of exposure to oil spills could be worsened by climate change, which is forcing polar bears to spend greater amounts of time on land in summer as sea ice melts away, the study lead author tells Carbon Brief.

Wild north

Republicans and Democrats have been at loggerheads about whether to drill for oil in the ANWR since the 1970s.

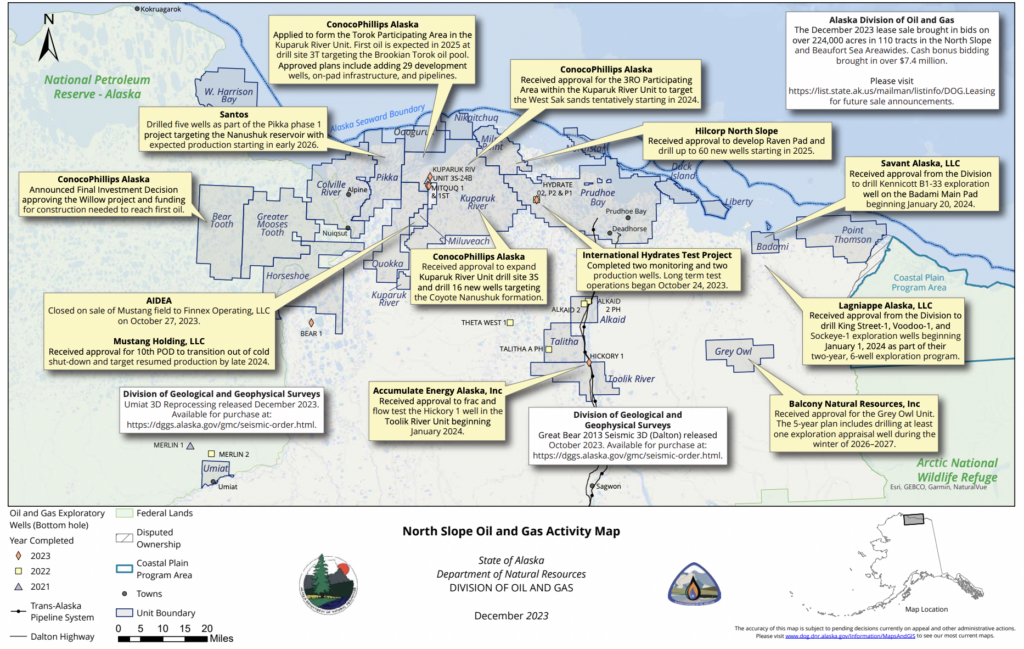

It is located in Alaska’s north slope, directly adjacent to a vast expanse of land that is a hotbed for oil and gas activity (see chart below). This activity includes the highly controversial Willow oil project, which was given final approval by Biden in 2023.

At present, there are currently around 2,000 oil and hazardous substance spills each year in Alaska, in areas where extractive activities already take place.

In 1989, Alaska faced one of the worst environmental disasters in US history when the Exxon Valdez oil tanker ran aground, spilling 11m gallons of oil.

Conservationists have fought to protect the ANWR, a wilderness supporting migratory caribou, wolves, all three North American bear species and hundreds of bird species. The refuge is also the home of the Indigenous Gwich’in and Iñupiat people.

But Republicans have long called for the ANWR to be opened up for drilling. According to Outside Magazine, Republicans have attempted to pass laws to enable drilling inside the ANWR nearly 50 times.

They were finally successful in 2017, when Trump passed a tax bill requiring oil and gas licensing rounds to be held for an area inside the ANWR.

However, on his first day in office in 2021, Biden issued an executive order suspending drilling in the ANWR pending an environmental review.

In 2023, interior secretary Deb Haaland cancelled the seven oil and gas licences issued in the ANWR under Trump, arguing the lease sale was “seriously flawed” for a number of reasons, including failure to “properly quantify downstream greenhouse gas emissions” from the projects.

Despite these efforts, the Biden administration is still required by law to conduct a second lease sale for the ANWR by December 2024, unless Congress is able to pass legislation undoing the provision set out in Trump’s tax bill.

Biden’s presidential campaign promised “no new drilling, period” on federal land and waters, but since entering office he has several times been compelled to hold new licensing rounds in various locations by Congress or the courts.

Dr Ryan Wilson, a wildlife biologist at the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska and lead author of the new study, says his research could help to inform decisions about issuing licences within the ANWR. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There is still an opportunity to inform where development and infrastructure would be allowed for the upcoming lease sale.”

Bear behaviour

For the study, the researchers used modelling to simulate how a series of “worst-case scenario” oil spills could affect polar bears resting in the ANWR.

Polar bears are known to be “especially susceptible to oiling” from spills, the researchers say. This is because oil can damage their fur, leaving them unable to thermoregulate in their harshly cold habitat.

According to the researchers, the ANWR provides an “important habitat” for polar bears from the Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation, a group of around 900 bears that are currently in decline.

The ANWR hosts the highest density of polar bear dens in the US.

When female polar bears are pregnant, they dig dens in the snow, where they give birth and care for their cubs for the first few months of their life. It is the “most vulnerable period in the polar bear’s life cycle”, according to Polar Bears International. Wilson tells Carbon Brief:

“We’re not sure why maternal polar bears are drawn to the ANWR coastal plain for denning, but records of denning events indicate that over the last 30-40 years there is a higher density of dens there than elsewhere on the northern coast of Alaska.”

The ANWR coastal plain also provides “important resting areas” and a “movement corridor” for bears during autumn, when sea ice is near its lowest levels, the researchers say.

At this time, polar bears feast on the remains of bowhead whale carcasses left behind by hunters from Indigenous communities.

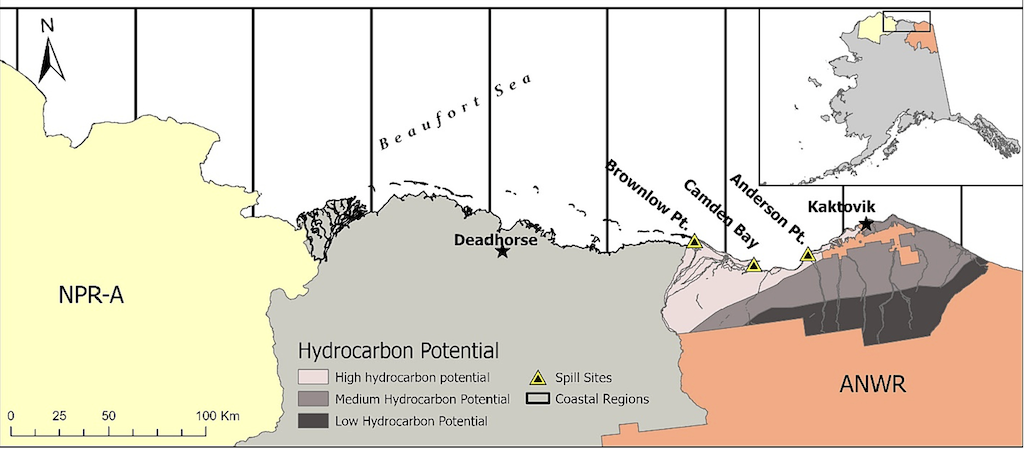

To understand how oil spills might affect polar bears, the researchers simulated spills from three locations along the north-western coast of the ANWR coastal plain: Brownlow Point, Anderson Point and Camden Bay. (These sites are represented with hazard symbols on the map below.)

These regions have the highest oil potential – and are also areas where polar bears come ashore to feed on whale carcasses, according to the researchers.

For each spill site, the researchers simulated an underwater pipeline release of 4,800 barrels of oil every day for six days, totalling 28,000 barrels. They then tracked the path of the oil spill for 50 days.

They simulated the oil spills in autumn, when the maximum number of bears would be using the ANWR.

To estimate how many bears would be exposed, they overlaid trajectories of simulated polar bear movements with the oil spills.

They found that a spill at Brownlow Point would be the most deadly, exposing up to 38 bears to lethal levels of oil. Meanwhile, a spill at Anderson Point would expose up to 28 bears, while a spill at Camden Bay would expose up to 19 bears.

All three of the spills would also expose up to 50-60 bears to sub-lethal levels of oil each week, the researchers find.

Mounting risks

While the simulations track the movements of oil and polar bears over 50 days, they do not consider any efforts that might be made to clean up the oil and take bears to safety, the authors say.

Because of this, they describe their results as a “worst-case scenario that could help managers and oil producers prepare for the most impactful scenario they might encounter with an active oil spill”.

Wilson adds to Carbon Brief that the risk to bears from oil spills has increased because of climate change, which is causing sea ice cover in the Arctic Ocean to rapidly shrink, forcing bears to spend more time on the land surrounding the ocean, including the ANWR:

“The primary risk to polar bears in the Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation is the loss of sea ice habitat due to climate change. The loss of sea ice is causing more polar bears to come on shore in summer and autumn for longer periods of time, which can lead to more human-polar bear conflicts, putting both bears and people at risk. This increased time on land also leads to greater risk to polar bears from an oil spill in the region.”

The study is “well-conceived and significant” says Prof Andrew Derocher, a polar bear researcher at the University of Alberta in Canada, who was not involved. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The risk to polar bears from an oil spill remains an ongoing concern and for a population like the one in the Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation, which has already declined in abundance due to climate change, the risk of additional mortality from an oil spill is a serious concern. An oil spill in Alaska as modelled would clearly have significant negative impacts on polar bears there.”

One aspect not covered in the study is how an oil spill would likely affect polar bear prey, including ringed and bearded seals, he says:

“If there were population-level impacts on the seals, this could be an additive impact that would further slow polar bear population recovery. In addition, there is a very high likelihood that polar bears would feed on dead and dying wildlife that were oiled in a spill – specifically, seals, walrus, possibly belugas and birds. Polar bears are consummate scavengers and this secondary form of impact isn’t addressed by this paper.”

He adds the study raises the important issue of being prepared for the environmental impacts of an oil spill in the Arctic:

“I believe that no jurisdiction is prepared for a significant oil spill in the Arctic. Our ability to respond is limited by preparedness, infrastructure and staff.”

Wilson R. R. et al. (2024) Potential impacts of an autumn oil spill on polar bears summering on land in northern Alaska, Biological Conservation, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110558

-

Alaska refuge drilling could threaten polar bears with ‘lethal’ oil spills