Roz Pidcock

30.07.2014 | 12:20pmThe combination of rising temperatures and air pollution could substantially damage crop growth in the next 40 years, according to a new paper. And if emissions stay as high as they are now, the number of people who don’t get enough food could grow by half by the middle of the century.

Burning question

Feeding the world’s rapidly growing population is a serious concern.

Research shows rising temperatures are likely to lead to lower crop yields. Other work suggests air pollution might reduce the amount of food produced worldwide. But nobody has considered both effects together, say the paper’s authors.

The two effects are closely related as warmer temperatures increase the production of ozone in the atmosphere. Here’s lead author Professor Amos Tai from the Chinese University of Honk Kong to explain.

The new study looks at global yields of the four principle food crops – wheat, rice, corn and soybean – and how they’re expected to change by 2050 under different levels of future emissions.

Together, these provide nearly 60 per cent of all the calories consumed by humans worldwide.

Global losses

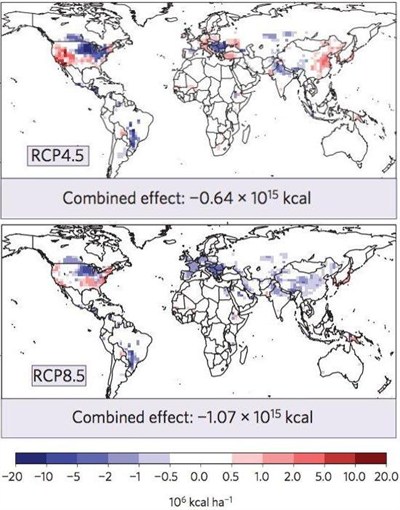

The maps below show some of the results.

The top panel is an optimistic scenario in which greenhouse gases stabilise at 630 parts per million (ppm) by 2100. For reference, we’re at about 400 ppm now.

The team compared this with what might happen if greenhouse gases continue to rise as rapidly as they are now. That’s the bottom panel.

How global crop yields are expected to change between 2000 and 2050 for RCP4.5 (top) and RCP8.5 (bottom). Total annual crop losses for each scenario compared to today are in the purple boxes below. Source: Tai et al. ( 2014).

Global food production falls by 2050 in both scenarios, as shown in the purple boxes below each map. If emissions stay high, total global yield falls by about 15 percent compared to today. But if emissions are kept low, the drop is reduced to just over nine percent.

The coloured shading shows how the total yield for all four crops varies region to region. Red is a higher yield than now, blue is lower.

Food security

Does this mean more people won’t get enough to eat?

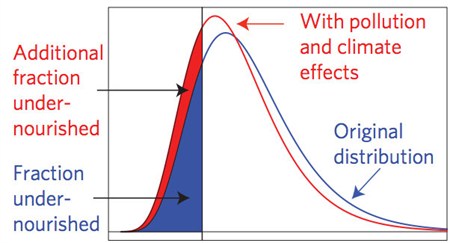

If emissions continue as they are, the drop in crop yields will means many more people globally will be undernourished, as the graph below shows.

The blue shading is the fraction of people in developing countries who consume less than the minimum amount of energy required per day. At the moment it’s about 18 per cent.

The red and blue shading together is the fraction of undernourished people by 2050 under the high emissions scenario. It’s about 27 per cent – about 50 per cent more than now.

The projections include expectations of a 40 per cent rise in global population by 2050. But they don’t take into account measures to increase resilience, such as changing farming practices.

Are we heading for global famine?

A headline in yesterday’s Daily Mail suggested the new research meant “climate change and air pollution will lead to famine by 2050”. But Tai tells us that’s a “little bit of a stretch”.

Famine is more complex than just food shortage, he explains:

“Famine is an extreme form of undernutrition with significant fatalities caused by not only crop failure but also a variety of socio-economic factors, which our study did not examine. The problem of undernourishment, in a more general sense, is usually more subtle but widespread and persistent”.

Different crops, different pressures

The scientists found not all crops are affected in the same way. For example, corn is more susceptible to heat, while ozone exposure is more of a problem for wheat.

How badly different countries are affected will depend on how bad air pollution is already and which crops they grow, the paper explains. For policymakers trying to decide how to deal with the problem, different countries may need to try different approaches. Tai tells us:

“Depending on the crops of interest and where you are, you may want to focus more on air pollution reduction or climate adaptation more.”

For example, tougher air quality regulations in the United States could lead to a sharp decline in ozone production, lessening the impact on crops.

“Talk to each other”

The authors are calling for greater collaboration between agricultural planners and air quality managers to set goals for food security and public health. Tai tells us:

“For policymakers and people in the field, including farmers, air pollution managers â?¦ they do have to talk to each other â?¦ We really call for greater collaboration between stakeholders of different interests and fields â?¦ they cannot just be concerned about their own fields because their objective is ultimately affected by decisions made in other sectors.”

Scientists know cleaning up air quality will have a significant impact on public health. This new research suggests cutting domestic air pollution as well as curbing warming could have big benefits for food security in some parts of the world too.