Roz Pidcock

31.01.2014 | 2:10pmClimate scientists have a puzzle to solve. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas and humanity produces lots of it – mainly from burning wood, mining fossil fuels and decaying waste in landfill.

But the amount we’re emitting doesn’t match up with how much scientists can detect in the atmosphere. More perplexingly, scientists don’t know why atmospheric methane is on the rise again, after a decade of the amount in the atmosphere staying the same.

Methane gas is more than 50 times better at trapping heat than carbon dioxide – making it a much stronger greenhouse gas over several decades, molecule for molecule. About one fifth of the global warming linked to human activity comes from methane, scientists estimate.

Understanding where methane is coming from is important for working out how global temperatures might change in the future. But as a new perspective piece in the journal Science explains, there remain many unanswered questions.

A brief history

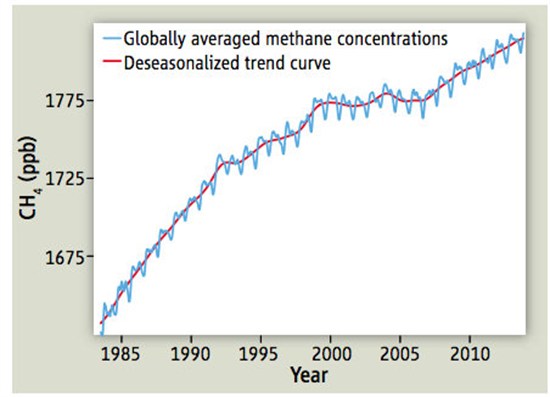

From the 1980s until about 1992, the amount of methane in the atmosphere rose sharply. Over the next ten years, the rapid growth slowed to just a quarter of what it had been.

In recent years the upward trend has come back but for a while in the early 2000’s, the concentration stopped rising altogether, even falling slightly in some years.

You can see this in the graph below, where the red line shows the trend with the yearly ups and downs (in blue) taken out.

Source: Nisbet et al. ( 2014)

These figures come from directly measuring the amount of methane present in the atmosphere. But there’s another way to estimate total methane emissions – measuring how much is coming from different sources across the globe.

Methane is emitted naturally from wetlands, but almost twice the amount produced naturally is emitted as a result of human activities, such as wood burning, agriculture, drilling and landfill.

Interestingly, during the early 2000s when measurements in the atmosphere recorded almost stable concentrations, measurements of methane sources on the ground told a different story.

When scientists combined all known sources of methane across the globe, the numbers they got suggested that far from staying still, methane emissions were rising quite dramatically.

“Top down” vs “Bottom up”

Lead author of the paper, Euan Nisbet from Royal Holloway University in London, says the mismatch could be because estimates of how much methane is being produced by different sources – so called ‘bottom up” estimates – might not be all that accurate.

As Nisbet explained to Climate Central’s Michael Lemonick:

“The measurements we make in the air are direct. Estimates of where methane is coming from, by contrast, are much less reliable. You estimate the contributions from gas leaks, count up the cows, estimate the emissions from wetlands. There’s obviously going to be a lot of error.”

On the rise again

The mismatch in “bottom up” estimates of total methane emissions and direct measurements of the concentration of methane in air – known as “top down” estimates – is only part of the puzzle.

Scientists are also not sure why the amount of methane in the atmosphere started rising again in 2007 – and has continued to rise steadily since then. The authors say in the paper:

“Just when scientists thought the methane concentration had stabilised, it rose again â?¦ The renewed rise in the methane burden prompts urgent questions about the causes”.

While scientists may not have all the answers just yet, Nisbet and colleagues explore some possibilities for what might be happening.

An Arctic solution?

In the poles, the main sources of methane are natural gas wells and pipelines. Scientists have also reported methane bubbling out of the shallow East Siberian Arctic Shelf as water temperatures are rising and beginning to thaw carbon-rich hydrate in the once-frozen sea bed.

But direct measurements of the overlying atmosphere don’t appear to be registering more methane entering the atmosphere from Arctic waters. In fact, atmospheric concentrations of methane over the Arctic have closely tracked the global average since 2007, the new paper explains.

Some scientists have raised the prospect that thawing hydrates and permafrost – carbon-rich soils on land rather than in the sea bed – could release huge amounts of methane very quickly once they start to collapse, causing a dramatic jump in global temperature.

But the authors of the new paper discount that idea – suggesting that if methane is being released, it’s not happening very quickly. They say in the paper:

“Long-term release of methane from hydrate is probable, but catastrophic hydrate emission scenarios are unlikely.”

If the answer to why atmospheric methane has been increasing since 2007 doesn’t lie in thawing Arctic permafrost, what else could be happening?

Leaky pipelines and landfill

In midlatitudes, where the UK and North America sit, methane emissions come mostly from the coal and gas industries, agriculture, burning wood, and landfill. The authors suggest these could have something to do with the rise in atmospheric methane since 2007. They say in the paper:

“In the United States, which has overtaken Russia as the largest gas producer, hydraulic fracturing is increasingly important. In Utah, fracking may locally leak six to 12 per cent of gas production to the air.”

The authors also point out coal production has expanded, most notably in China. Methane is often found with coal and the suggestion is that some could be escaping as the coal is mined.

Wetland culprits

But while the authors say there’s likely to be some contribution from human activity, the link with rising atmospheric concentrations is yet to be made conclusively. The chemical “fingerprint” of the methane in the atmosphere suggests a natural source, rather than an anthropogenic one.

Decomposing vegetation in tropical wetlands is the single biggest natural source of methane. And as Nisbet explains to Climate Central, the amount wetlands are kicking out has increased:

“In the southern hemisphere especially, but also in the northern tropics, a series of really wet years has caused wetlands to expand”.

The question of how much methane we’re putting into the atmosphere is a lot less well understood than other greenhouse gases – better measurements are clearly needed. So while methane may not be the biggest source of warming – that distinction goes to carbon dioxide – this shouldn’t diminish efforts to resolve the many unanswered questions, the scientists warn.