Mat Hope

13.11.2014 | 3:00pm- The US and China both make new pledges to cut emissions.

- The pledges are not enough to prevent temperatures rising by more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels.

- Negotiators say the agreement is vital to policymakers’ chances of agreeing a new climate deal in 2015.

The US and China yesterday agreed new climate targets. The deal is being hailed as “historic” and “a watershed moment for climate politics”. Some have questioned whether the targets are ambitious enough to help the world avoid the worst impacts of climate change, however. Here’s our guide.

China’s emissions to peak in 2030

China has pledged to ensure emissions peak in 2030. It has also promised to aim to produce 20 per cent of its energy from low carbon sources by the same date.

No one knows how high the country’s emission peak will be and it’s unclear how much carbon dioxide China will be emitting when 2030 comes around.

Assuming China’s emissions continue to rise at the current rate of about three per cent a year for the next sixteen years, the country will be emitting around 16 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year by 2030, according to thinktank Climate Action Tracker.

China’s officials don’t think emissions won’t get that high, however. They anticipate economic growth slowing to about four or five per cent a year and low carbon energy sources such as wind, solar, and nuclear will be ramped up. They believe that the next fifteen years will see China’s economy shift towards less polluting services and away from heavy industry, the Financial Times reports.

Emissions will peak at a lower level if China’s government takes aggressive action to curb pollution. A 2011 study by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests China’s emissions could peak at 9.7 gigatonnes if the government implements ambitious climate policy, the New York Times reports.

China’s emissions may have peaked in 2030 anyway

Critics of the pledge have suggested China’s emissions would peak around 2030 without government intervention. That might suggest the new target isn’t as big a deal as officials are making out.

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory study suggests economic trends means China’s emissions may peak between 2030 and 2035, regardless of government efforts to reduce pollution, the New York Times says.

The China Academy of Social Sciences last week said a slowdown in the number of people moving from the countryside into cities means China’s industrial emissions could peak around 2025 to 2030 and start to fall by 2040, Reuters reports.

So while it is politically significant that China has set a year that its emissions will peak, whether the pledge represents any new commitment to action remains to be seen.

China’s pledge is not enough to avoid two degrees of warming

China’s target probably isn’t enough to prevent temperatures rising by more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels, according to Climate Action Tracker.

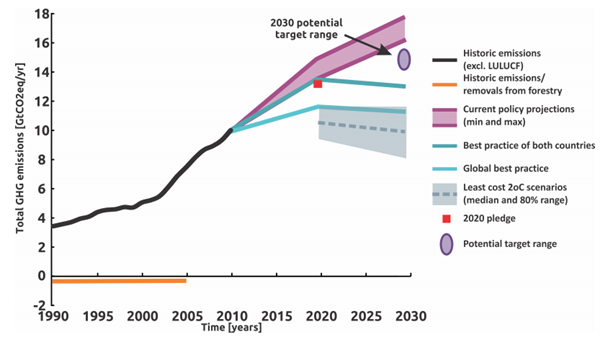

It says China’s peak emissions are likely to “lie far above a two degrees consistent emission pathway”, as this graph shows:

The purple circle is where Climate Action Tracker expects China’s emissions to be in 2030, based on yesterday’s announcement. The dotted line and grey box show the emissions pathway that allows policymakers to prevent temperatures rising by more than two degrees at least cost.

As you can see, there’s quite a big gap between the two. Even with the new target in place, China could overshoot the necessary emissions reductions by around 50 per cent.

China’s pledge to build lots of low carbon energy isn’t that ambitious

China’s pledge to get 20 per cent of its energy from renewables and nuclear by 2030 is also not that ambitious, experts say.

China got 9.8 per cent of its energy from sources not linked to fossil fuels at the end of 2013, and the government intends that to reach 15 per cent by 2020, the New York Times points out.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) says China’s plan to increase its share of renewable energy to 20 per cent is broadly in line with a scenario where countries make some, not particularly ambitious, efforts to cut emissions. In the IEA scenario that sees the world prevent two degrees of warming, China gets 26 per cent of its energy from renewables by 2030, the Guardian reports.

China’s new target is still significant in the context of global efforts to decarbonise, however. The Natural Resources Defense Council’s Jake Schmidt tells the New York Times, “[y]ou’re talking about 20 percent of a huge economy being based on non-carbon-dioxide-emissions sources. That’s significant.”

The US’s new pledge isn’t more ambitious than its previous targets

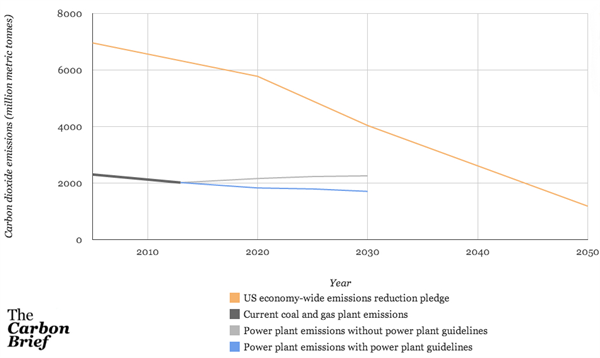

The US has pledged to cut emissions by up to 28 per cent by 2025, compared to 2005 levels.

This is on top of pledges made by President Obama as part of his Climate Action Plan last year. The US already had targets to cut emissions by 17 per cent by 2020, 42 per cent by 2030 and 83 per cent by 2050.

The US’s new pledge isn’t any more ambitious than its existing commitments were. President Obama’s previous pledges implied the US would emit around five gigatonnes of carbon dioxide in 2025, according to Carbon Brief’s own analysis. That’s if you assume the country is going to cut emissions in a linear fashion between 2020 and 2050. The new pledge implies about the same, Climate Action Tracker’s analysis suggests.

However, the US is currently not on track to hits its 2020 goal, Climate Action Tracker says. So that means it will have to do more if it wants to hit any of its new or existing goals.

The US’s emission reduction targets could be under threat

The future of Obama’s emission reduction targets is uncertain, thanks to the US’s domestic politics.

The Republican party just took control of Congress, the US’s legislature. The politician expected to become leader of the Senate, Mitch McConnell, has made rolling back President Obama’s climate plan a priority. He said he was “particularly distressed” by yesterday’s announcement, CBS reports.

The Senate controls the government’s budget, and is expected to attempt to withhold funding to the Environmental Protection Agency, the main body tasked with implementing the president’s climate action plan. That could make it difficult for the US to achieve Obama’s pledged cuts.

Obama’s pledge could also be undone by a new president. Elections are due next November, and the Republicans are hoping to deliver a candidate to the White House on the back of their midterm election success.

Nevertheless, US author and climate activist Naomi Klein writes that the deal is “tactically smart”:

“…by tying the emission reduction targets of both countries together in a bilateral deal, the President is making sure that his successor will have to weigh any desire to break these commitments against the risks of alienating America most important trading partner.”

The US-China deal is highly significant for international climate politics

Even if the commitments from the US and China are perhaps not as ambitious as they first seem, the nature of their announcement is hugely significant.

World leaders have set a deadline to agree a new global climate deal by the end of next year, at a big conference in Paris. The US-China deal shows the world’s two largest emitters are willing to negotiate.

This contrasts with a similar political moment five years ago where countries failed to agree a new deal at a similar summit in Copenhagen, partially due to China and US obstruction.

International climate talks have stalled since, with countries waiting to see whether the US and China would commit to taking action to curb emissions.

“I believe the main benefit of this commitment [by US and China] is creating political momentum for other countries as well. It will be very difficult, after this move by the US and China and Europe, not to be a part of finding a solution to one of the biggest problems of mankind,” the IEA’s chief economist, Fatih Birol, told the Telegraph.

EU climate and energy commissioner Miguel Arias Canete says the deal is a “positive, timely, important step in the right direction”, RTCC reports.

The UK media seems to be interpreting the deal in this way. It “unblocks the road” to a new agreement in Paris, a Guardian editorial argues. Suddenly, a low carbon world “seems possible”, a Telegraph editorial says.

The deal shows shows countries will not be going it alone

One way in which the deal adds impetus into the negotiations is by undercutting arguments that countries should not take climate action before the world’s two largest emitters.

By explicitly targeting a peak emissions year, China has shown it has the “political will” to take action on climate change, TIME argues.

The Council on Foreign Relations’ Michael Levi tells the magazine:

“China has typically gone out of its way to assert its independence in anything climate-related. That approach would usually have led it to announce major goals like these in a clearly unilateral context – even if they were developed in tandem with the United States. Rolling them out together with the United States says that China is increasingly comfortable being seen to act as part of an international effort”.

The US-China deal is politically historic

So the deal is historic. It is the first time the world’s two biggest emitters have worked together to show they’re willing to take action on climate change. And that could be good news, politically.

It shows that “[i]f the two biggest players on climate are able to get together, from two very different perspectives, the rest of the world can see that it’s possible to make real progress”, Timothy Wirth, vice-president of the United Nations Foundation tells Reuters.

If other countries follow suit, it could have a huge impact on global greenhouse gas emissions, as this analysis from consultants Climate Interactive shows.

It assumes all developing countries cap emissions in 2030, as China has pledged to do, while all developed countries make the same efforts to cut emissions as the US has.

If that were to happen, 2,500 gigatons of carbon dioxide could be prevented from being emitted into the atmosphere, it says. That outcome, or something like it, will be something for negotiators to shoot for at Paris. Hence all the superlatives surrounding the deal.

But there’s no guarantee that will happen, the Washington Post points out. Countries are due to announce their targets by the end of March 2015 as part of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s ongoing efforts to garner support for a new global deal.

When they do, the impact of the US-China deal on global efforts to combat climate change will become much clearer.