Did Santa bring any of these this Christmas?

We asked 25 thinkers, writers and journalists a simple question: What books or readings inspired you to get involved in climate change-related work?

We were expecting to get back a list of books – and we did. But we also got some interesting insights into why people work on this issue, why they started, and why they carry on.

Mike Mann

Professor of meteorology at Penn State University. Author of The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars.

“Two books that inspired me as a young scientist were The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen J. Gould and The Demon-Haunted World by Carl Sagan. Gould and Sagan were both heroes of mine, premier scientists in their domains (evolutionary biology and planetary science respectively), and also gifted communicators.

“Both books explore the pernicious societal impact of antiscience and pseudoscience. In Gould’s case, the bad science behind early 20th century dogma contending a racial basis to human intelligence. In Sagan’s case, it was the tendency for human beings to hold irrational views about matters such as faith healing, extrasensory perception, and UFOs.

“Both exemplify how scientists can be effective advocates for an informed public discourse over societally-relevant matters of science.”

For an 8-year old Maureen Raymo, Jacques Cousteau’s love of the ocean was infectious

Maureen Raymo

Professor of palaeoceanography at Columbia University and author of Written in Stone.

“I’ve been around a long time and the books that inspired me as a grad student were written in the 80s and are now fairly obsolete. However, my greatest inspiration was a person, Jacques Cousteau (and his books and TV shows). From the age of eight I wanted to explore the ocean.”

Daniel Ortega

Ecuador’s lead climate negotiator.

“For over 50 years, Rachel Carson’s masterpiece ‘ Silent Spring‘ has continued to provoke controversy and public awareness. This book made the case that our actions have an impact both on nature and humans, and that the remedy to environmental problems can be worse than the original illness.

“Reading Carson’s book during the earlier years of my training to become an agronomist, while working in the fields and inside forests in rural Latin America, inspired me to reflect on climate change, its causes and impacts on poor countries and their efforts to eradicate poverty.

“Since then I have worked on climate at every level of society, from social movements up to international negotiations, hopefully learning from the achievements of Ms Carson’s book.”

Natalie Bennett

Leader of the Green Party of England and Wales.

“I’d recommend, for readers well into their science studies, or readers prepared to stick with some fairly technical stuff, Oxygen: A Four Billion Year History by Donald E Canfield.

“It explains both the incredible recent progress of the science (lots of what I was taught in school is now clearly wrong), and also still how little we know about the massive past changes in our world that could help inform us about the risks of the Anthropocene. I’ve written more here.”

David MacKay

Professor of engineering at the University of Cambridge and former chief scientific adviser to the Department of Energy and Climate Change.

“I recommend Challenged By Carbon by Bryan Lovell. This is an unusual book, intertwining two stories, one of them 55 million years old, and one less than 55 years old. For the older, slower story, Dr Lovell delves into the details of the geological history of Iceland, the North Atlantic, and the North Sea.

“The younger, rapidly-moving story is the `insider’s view’ of how the oil industry, in the last 15 years, changed its mind about human-caused climate change. Starting from positions of climate inactivism (by which I mean ‘yeah, it may be true, but there’s lots of uncertainty and there’s no point doing anything, and we oppose greenhouse-gas-reduction treaties’) or outright denial, the big oil companies, driven by the science, changed their tunes.”

Ruth Davis

Political director of Greenpeace UK

“I am not a Utopian. I think the best that I can do is battle dystopia – and leave the door open for human potential. And so the book I would recommend is a story about ‘little’ people toiling against the tyranny of big lies – against those sweeping ideological certainties that disconnect us from reality and enable war, cruelty and poverty to ride triumphant.

” Alone in Berlin by Hans Fallada tells the story of an elderly German couple whose son is killed in the Second World War. Their hearts are broken, and they set out on a brave, funny and finally doomed mission to tell the truth to their fellow citizens.

“The example of remaining consistently faithful to a politics that protects the intimate and domestic is one I find inspiring and in this case awe-inspiring. I would like it to inform all my work, not just my work on climate change.”

Richard Betts

Leader of the climate impacts team at the Met Office.

“I was particularly inspired by Gaia: A new look at life on Earth by James Lovelock, which I read in 1991 when doing my MSc in meteorology. I was fascinated by the idea that life plays a central role in the climate system, and this has led to the well-established field of Earth System Science which is where I see my own research contributing.

“I acknowledged Lovelock in my first paper in Nature on climate-vegetation feedbacks, which led to a set of new models in the Met Office Hadley Centre that are now central to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment reports.”

Ro Randall

Psychotherapist researching climate change.

“My choice isn’t an old favourite but a new one, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate [published tomorrow, 16 September]. Klein covers all bases with a clear systematic understanding of the issues.

“She’s curious about the everyday denial which allows us to simultaneously know but ignore the significance of climate change. She’s courageous in investigating our abuse of nature. She’s savvy about politics and the deadly influence of free-market fundamentalism. She takes on the arguments about growth.

“She’s clear-headed about the need for state intervention. She’s encouraging about the possibilities of building solidarity. She’s empathic with and angry about the suffering of ordinary people. And she weaves it all together in clear, compelling prose. Everything you need in one book.”

Oliver Morton

Briefings editor of the Economist and author of Eating the Sun: How Plants Power the Planet.

“Two big influences on me: The Ages of Gaia, by Jim Lovelock – probably his best book. I already had a sense of earth system science and of the deep past, so the book simply fascinated me, and deepened both my knowledge of and my feelings about the planet. If I hadn’t been prepared for it I think it would have blown my mind completely.

“And the Martian Trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson. These excellent books are not just among the best science fiction novels of recent decades. Their central theme of terraforming makes them a long and subtle look at political and personal beliefs in the context of changing how a planet works.

“The estrangement that comes from making the debate about Mars and not (directly) the Earth makes the effect all the stronger, opening up the question of what it really means to be an environmentalist.”

Jules Verne – an early thinker about the risks of geoengineering, it turns out

Brigitte Nerlich

Professor of science, language & society at Nottingham University.

“If I had to choose a text, but only if I had to, because it would be a lie to say that a particular text ‘inspired’ me to think about climate change, I would point Jules Verne’s The Purchase of the North Pole.

[Originally titled Sans Dessus Dessous, the book takes readers on a flight of imagination in which a group of entrepreneurs plan to use a giant cannon to alter the earth’s tilt, so ending seasons, melting the North Pole and making accessible vast coal reserves under the Arctic.]

“I read this book many years ago when studying French literature and had almost forgotten about it. However, it all came back to me when beginning to explore the social and cultural roots and impacts of debates about climate change in general and geoengineering in particular.

“Debates about the climate and human interference in the climate system have a long history, not only in science, but also in popular culture. Understanding these debates needs knowledge of both.”

Tom Burke

Green thinker and co-founder of environment thinktank E3G.

“There are two quotations from the Duino Elegies by Rainer Maria Rilke that have been important for me in my thirty year involvement in climate change. They come from the Duino Elegies, Rilke’s masterpiece which he began composing in June of 1914.

“The first is ‘strange to see all that once was relation so loosely fluttering, hither and thither, in space’. This line sums up for me what we are fighting for. Climate change will destroy ‘all that was once relation’ – everything that is best about this planet both from what nature has done and what mankind has done.

“The second quotation is ‘Is it not time that in loving we learnt to endure as, quivering, the arrow endures the string, to become in the gathering outleap something more than itself’. There are many dark days in the fight to keep the climate safe for civilisation and I find a comfort in these words when my spirits are low.”

Prakash Mathema

Nepalese climate expert and chair of the Least Developed Countries group at the UN climate negotiations.

“Climate change is undermining the development efforts of Nepal and other Least Developed Countries, making it even more difficult for us to reduce poverty and enhance economic growth. My firm belief is that the UN climate convention is the only legitimate global forum where international cooperation can best deliver such an agreement spurred me to join the climate change negotiations process.

“I have been inspired by Hot, Flat and Crowded by Thomas Friedman, which asserts that the best way forward is to replace wasteful inefficient energy practices with a strategy for clean energy, energy efficiency and conservation.

” Toward a Binding Climate Change Adaptation Regime by Mizan Khan is another inspiration. It sets out a framework for establishing a legally-binding adaptation regime under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, with the view to reducing the gap between the focus on mitigation and adaptation.”

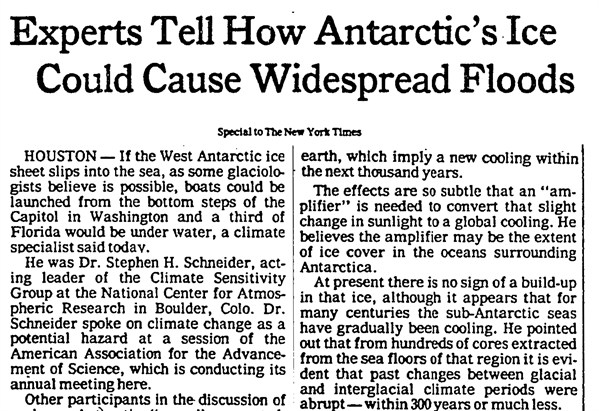

A New York Times article of 8 January 1979 inspired Ken Caldeira

Ken Caldeira

Climate scientist at the Carnegie Institution Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University.

“I was inspired to get into climate science by reading the daily newspaper. In 1979 I read a story in the New York Times about the potential for greenhouse warming to melt ice sheets and result in dramatic sea level rise. I then got my hands on some early reports on climate change.

“Back then, there was no Internet and you had to either go to libraries or even write to people by postal mail. It is far easier to get information now, but also far easier to find bad information. Eventually, I went to graduate school and became a scientist which was one of the best decisions I have ever made.”

Mike Hulme

Professor of climate and culture at Kings College London and author of Why We Disagree About Climate Change.

“Hubert Lamb’s Climate, History and the Modern World surveys a huge canvas and he paints in eloquent terms the relationships between climate and society over the last 2,000 years. The book first established for me that, whatever the balance of factors that contribute to a changing climate, climate should not be regarded as a fixed boundary condition for society.

“Although Lamb was never entirely convinced by the arguments for the enhanced greenhouse effect being the dominant cause of climate change, he had grasped before all of us that climate and society are tightly coupled systems and co-evolve on all time and space scales.”

Ed Hawkins

Climate scientist at the University of Reading. Runs the Climate Lab Book website.

“The Callendar Effect, by James Fleming describes the work of Guy Stewart Callendar in establishing the role of carbon dioxide in warming the planet. Callendar was the first person to demonstrate that the Earth was warming in 1938, and that increases in atmospheric CO2 were at least partly responsible.

“These feats are even more impressive given that he was an amateur meteorologist, and did all the tedious calculations by hand. The book helps highlight that the basic physics behind climate science was established many decades ago.”

Geoffrey Lean

Environment correspondent at the Telegraph.

“I started to write about climate change in the 1970s, inspired by Barbara Ward’s and Rene Dubos’ classic Only One Earth. But the book that most impressed the importance of the issue upon me was Nigel Calder’s The Weather Machine and the Threat of Ice published in 1974.

“Calder’s book was concerned with global cooling not warming and perhaps marked the climax of the short-lived concern that the major danger was of a new ice age – a concern now routinely mocked by climate contrarians, somewhat paradoxically because he was a prominent sceptic himself. But it introduced to me – and the general public – the important concept that climates can change both rapidly and radically.”

Alice Bell

Researcher and writer on the politics of science, technology and the environment. Contributor to the Road to Paris blog.

” The Discovery of Global Warming by Spencer Weart doesn’t offer a eureka moment. As the author stresses, our knowledge of climate change has been an elongated process of multiple discoveries, scientific and political.

“Such granular development might seem a bit depressing and/or boring. But this book is both engrossing and liberating. It’s a useful explainer of how we got to here with respect to climate change, but it’s also a book of hope. Above all, it’s a story of social awareness and change, with a real sense that more change is possible.”

Guy Newey

Head of policy at Ovo Energy, and former head of energy and environment at Policy Exchange.

“I tend to think the most useful books about climate change are often those which have nothing to do with it, but make general arguments that are applicable to the debate (John Kay’s Truth About Markets is the best example).

“But Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air by David Mackay is an excellent exception. It drills down into the detail of what a low-carbon UK actually means, challenges woolly thinking on the argument that decarbonisation is easy and makes the reader confront difficult choices. It is a wonk reference work and we use it most weeks in our internal discussions.”

James Painter

Climate journalism researcher and head of journalism fellowship programme at Oxford University’s Reuters Institute.

“It is virtually impossible to write a successful novel about climate change. The science gets in the way, the characters too easily become advocates for action or villains for opposing it, or plots can be too driven by visions of apocalypse.

” Flight Behaviour by Barbara Kingsolver is the exception. Her knowledge of etymology is worn lightly, her characters are drawn with sympathy and insight, and her narrative is compelling. She even knows about science communication. The scientist at one point complains that ‘as long as we won’t commit to knowing everything, the presumption is we know nothing’.”

Katharine Hayhoe

Director of the Climate Science Centre at Texas Tech University and science advisor to climate change documentary series ‘Years of Living Dangerously‘.

” Red Sky Warning by Gus Speth places climate change within the larger context of human society and development on this planet and what it will take to ensure a truly sustainable life for ourselves and our kids.”

Mark Brandon

Climate scientist and ice expert at the Open University.

“I love Fixing Climate by Robert Kunzig and Wallace Broecker because it plays to my natural optimistic personality. It’s a book of two halves.

“In the first we get a fantastic overview of how climate history was discovered by one of the pioneers. It spells out what the climate problem is and what may very likely happen in the near future.

“In the second half Kunzig and Broecker explain what we could actually do to solve the situation we have mostly unknowingly created. It’s very well written and is compelling stuff. I am surprised it is not more popular.”

Max Boykoff’s copy of The Carbon War is well-thumbed

Max Boykoff

Climate media researcher and associate professor, Colorado University.

“I can point to Jeremy Leggett’s The Carbon War. Published in 2001, it is an early take on the politics of climate change. His sharp accounts of the foundational science-policy interactions at the international scale still make this a useful set of insights that shed light on continuing climate change politics in 2014.

“The crescendo of the book in Kyoto in 1997 is worth revisiting as we move through critical UN climate meetings in Lima, Bonn and Paris over the next 15 months or so. It inspired me to do work I continue doing now on the cultural politics of climate change – my heavily dog-eared and marked up copy remains close by in my office.”

Jonathon Porritt

Environmentalist and author of Capitalism As If the World Matters.

“I would like to put forward Reinventing Fire by Amory Lovins and others at the Rocky Mountain Institute. Lovins has been summoning up visions and blueprints for an ultra-low-carbon world for around forty years, so he really knows what he’s talking about by now. Reinventing Fire fizzes with intellectual and practical energy of every kind. It’s like sticking your finger into a scintillating and wholly uplifting energy source – without the pain!”

Phil Jones

Director of research at the Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia.

“Nothing really inspired me to get where I am back in the 1970s (I finished my PhD in 1976/7). At that time it was just a job. It has worked out well, but this was basically chance. When I started it was climate research. There wasn’t climate change then!

“We have prospective MSc students wanting to read something before they come. I always recommend the Rough Guide to Climate Change – which seems now in its third edition. Not really inspirational, but gets across simply many of the points we want to instill into a new set of students.”

Bryony Worthington

Labour life peer and founder of carbon trading campaign group Sandbag.

“The book that inspired me when I was starting to get interested in climate change was Natural Capitalism, in particular Chapters 12 and 13. It’s a fascinating and stimulating read that influenced me when I was thinking of starting Sandbag. Even today we often quote the great line: ‘In God we trust: all others bring data.’

“It was in this book I first came across the idea of Negawatts and the idea of creating markets in increased resource efficiency. There is still a long way to go to bring many of these ideas to life but the overwhelming logic of them is compellingly presented in this book.”