Sophie Yeo

26.10.2015 | 10:13amCountries have completed the last round of negotiations before a landmark meeting in Paris in December, where they have agreed to sign a new UN agreement on climate change.

Despite the urgency, the week produced little consensus, with issues such as finance proving fractious till the end. Nonetheless, parties produced a new draft text, which will form the basis of the final negotiations in Paris.

The document does little to narrow down the options for the final deal, but crystallizes the key debates that negotiators and ministers will attempt to resolve in just over a month’s time. Christiana Figueres, the executive secretary of the UNFCCC, told the Chatham House climate conference in London today that the new text was “now party owned” and, as a result, was “not biased, but balanced”.

The beginning

On 5 October, the co-chairs of the negotiations drafted a text that they hoped parties would use to inform their work in Bonn.

Slimmed down from 76 pages to a more manageable 20, the document removed some of the substance and options contained in previous incarnations. Some resistance was expected, as countries struggled to ensure their positions remained on the table for as long as possible.

What, perhaps, came as more of a surprise was the strength and hostility of the opposition to the text, which was swiftly christened the #UStext on Twitter as it faced accusations of imbalance in favour of the developed countries.

A South African spokesperson from the G77+China — a group comprising 134 developing nations — said that it evoked “memories of apartheid”. Developed nations, including the EU, also said their ideas had been excluded from the text.

This prompted a flurry of speculation in the corridors over whether the choice to release a bare-bones text had been a serious misjudgment on the part of the co-chairs, or a masterstroke — because after the initial back-and-forth in the opening plenary, parties got to work on reinserting their options, with the co-chairs releasing a new-and-improved edition at 4am the next morning.

The result: a slimmed-down text (34 pages) that countries felt they now owned and were happy to use as the basis for negotiations.

Slow start

The introduction of a party-approved text did not mean the rest of the week was plain sailing. Debates, accusations, and, on some occasions, undisguised hostility, continued to spring up from various quarters throughout the week.

The underground café of the UN campus in Bonn quickly filled with irate civil society observers, who had been barred from attending the meatiest negotiating sessions — the seven “spin-off groups” where parties were getting down to negotiating the most important and controversial elements of the UN agreement.

Even so, within these spin-off groups, progress was slow. On Wednesday, three days into the five-day negotiations, France’s climate envoy Laurence Tubiana warned delegates that progress was not taking place quickly enough.

“I don’t think this way of working is going to lead us to where we need to be by the end of this week,” she said.

Old divisions re-emerge

The week was marked by the resurgence of old debates around whether developed and developing nations should be treated differently in the text – an issue known as “differentiation”.

When countries agreed to start the process towards a new UN climate deal in 2011, everyone concluded that it should be “applicable to all”. This was a departure from the previous approach of the Kyoto Protocol, where only rich nations were obliged to take action.

Nonetheless, this has led to two competing narratives at the UN climate talks. There are those who claim that the world has changed since the division between rich and poor nations was drawn up in 1992, and those who say that this 1992 division should remain as the basis for negotiations on the grounds that deep inequalities remain.

There was some hope that this impasse had been breached back at the Lima COP late last year, when countries agreed that countries “in a position to do so” would take various actions — a flexible, evolving approach that it was hoped would replace the old binary split.

But old tensions on this topic reared their head again this week in Bonn. Elina Bardram, the EU’s lead negotiator, told journalists:

We consider it somewhat unfortunate to see that some countries are reverting to very rigid and somewhat outdated rhetoric which divides the world into developed and developing countries according to income levels as they were in the 1990s, and this is at the same time as we know all parties, and, indeed, the world outside these negotiations, are well and fully away that to be effective the new agreement must reflect today’s reality and evolve as the world does.

Finance and loss and damage

Differentiation touches upon almost all elements of the UN deal under negotiation, but it was on the subject of finance where the debate was at its most intense.

There was the hope that countries would spend the week coming up with “bridging” solutions that would create some compromises on the text. There were a few notable efforts to do so. A proposal by the small island states and least developed countries on how to reduce emissions was celebrated by many of the green groups observing the negotiations.

Nonetheless, two negotiating blocs — the G77 group, and the US-led Umbrella Group — found themselves at loggerheads with two conflicting proposals. At the centre of the debate was which countries should contribute to the international pot of climate finance.

While the Umbrella Group is keen to broaden the donor base to all countries “in a position to do so”, the G77 wants to ensure that finance continues to flow exclusively from developed to developing nations.

The Umbrella Group is also keen that the agreement should reference various sources of climate finance, such as private finance and development banks, whereas the developing country bloc is also insistent that the agreement should deal only with public finance. South Africa’s Ambassador Mxakato-Diseko said that to do otherwise would leave developing nations to the “whim of charity”.

Loss and damage — which is the issue of how the most vulnerable countries might be compensated for any irreparable damage caused by climate change — was another topic that continued to divide. Some countries hope to see it embedded within the heart of the agreement, while the Umbrella Group has suggested it be removed from the agreement.

This proved an emotive suggestion. “Not to have loss and damage in the agreement, it is equivalent to climate denial,” said Juan Hoffmeister, a negotiator from Bolivia.

A new text

The outcome of a week of negotiations were consolidated on Friday into a new, longer text. Swelling to 51 pages, the document contains all of the options that countries want to see negotiated in Paris.

The proliferation of ideas makes it clear enough that there has been little convergence between negotiators on the key issues at stake.

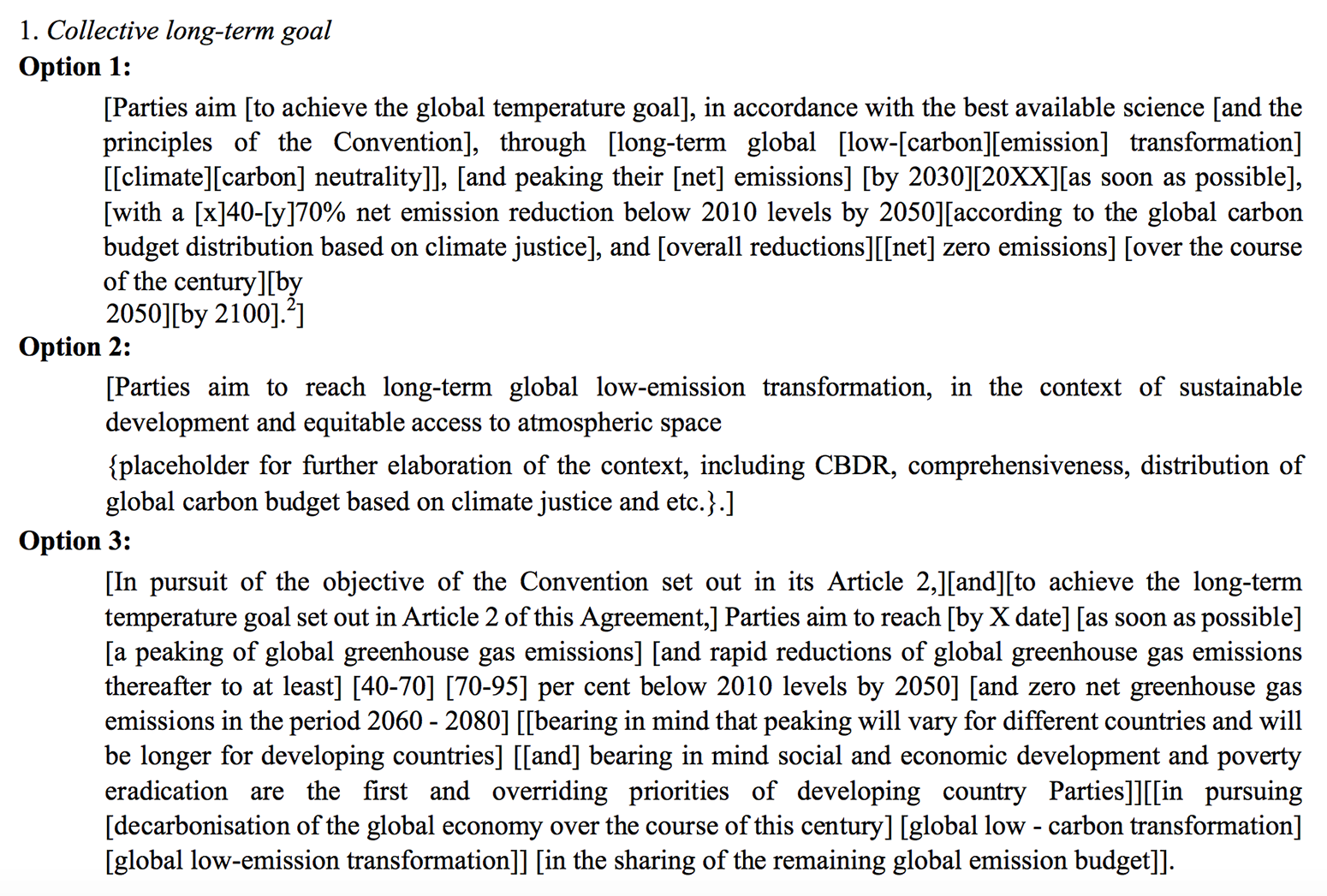

For example, the paragraph on the “long-term goal”, one of the crux issues of the deal that describes the overall direction of travel, has swollen to three options, each containing various internal options, as indicated by the square brackets.

Options 1-3 of the collective long-term goal, under Article 3 (Mitigation). Source: UNFCCC.

Significantly, this section now contains the notion of long-term decarbonisation again, which was absent from the October 5 text. This was reinserted at the bidding of the US, in line with the language agreed by the G7 in June.

The text also contains four different options on how to differentiate between developed and developing countries when it comes to reducing emissions. Possibilities range from having no specific additional language on differentiation, to requiring only developed countries to submit progressively more ambitious targets over time. This reflects the week’s resurgent debate over differentiation.

There are two finance options in the text, closely resembling the opposing submissions put forward by the developed and developing country blocs during the week.

On the controversial issue of loss and damage, there are two options. One of these options is not to include loss and damage.

At the closing session of the meeting, French envoy Tubiana said that negotiators had never really got down to the business of negotiations during the session.

Nonetheless, the text does set out a clear menu of options that can be presented before ministers when they meet in Paris in November, ahead of the final round of negotiations.

For Sarah Blau, a negotiator from Luxembourg, which currently holds presidency of the EU, this represents some progression. She said: “I think there was a lot of progress done to clarify options… Once you have two or three options outlined possible landing grounds get clearer.”

Observers and negotiators alike highlighted the importance of the high-level political events taking place during November, as the sense grew that negotiators, bound to follow orders from their capitals, would be unable to make much further progress on the hard decisions at stake.

As well as the ministerial event in Paris, there will be a G20 summit in Turkey, providing another key opportunity for smoothing over differences at the highest level. Heads of state are also expected to show up at the start of the Paris talks in order to give direction to the negotiations. Louisa Casson, policy advisor at environmental think-tank E3G, told Carbon Brief:

As countries have taken a stronger ownership of the draft text this week, we’ve got a clearer idea of what needs to happen up to COP21. In the next month, we need to connect the politics to the text. We need to get much more clarity on finance beyond 2020 and address loss and damage too. Heads of state should use the G20, bilateral meetings and the Commonwealth gathering to articulate their commitment to a dynamic and enduring Paris regime that leaves no one behind.

Success in Paris will partly depend on how far politicians are able to inject some last minute political will into this long and winding process over the coming month.

Timeline

- 30 October – UN releases its “aggregation” report of INDCs

- 8-10 November – Ministerial pre-COP, France

- 15-16 November – G20 Leaders’ Summit, Turkey

- 30 November – 11 December – 21st Conference of Parties, Paris

Media reaction

Carbon Pulse said the draft text had swollen to a “heavily-bracketed 34 pages”, primarily in response to concerns from developing nations. The BBC was one of several outlets to raise the spectre of Copenhagen, the failed climate talks of 2009. While some in Bonn heard echoes of the bitter rich-poor divisions that broke Copenhagen, many others felt things were in now a far better place, the BBC said. Disputes over financing for poor nations hampered the talks, reported Reuters, with developing countries saying climate finance is “the” core issue.

Striking a more optimistic note, the Guardian said the latest draft text shows countries are close to consensus. The focus now turns from climate negotiators to ministers and world leaders, said Climate Home, with some issues said to be unresolvable at negotiator level. French diplomat Laurence Tubiana attempted to dispel one Copenhagen ghost, insisting there is no secret text being prepared by France behind the scenes.

In a comment piece, BusinessGreen editor James Murray asked if the negotiations are having a last-minute wobble. In an article for Ensia, Guardian environment correspondent Fiona Harvey set out “what it will take for success” at Paris. Meanwhile, the Obama administration is ramping up efforts to secure domestic backing for a climate deal, reported the Hill.

The talks in Bonn ended with tension over who should pay for climate action, said Politico. In his Dot Earth blog, Andy Revkin said the battle over climate finance has moved into the foreground and “could still do for Paris what the emissions fight did for Copenhagen”. Meanwhile, a guest legal commentary for Climate Home looked in detail at possible language on loss and damage.

Main image: Plenary hall on Day 1 of the Bonn Climate Change Conference. Credit: Sébastien Duyck/Flickr.

-

Old battlelines resurface as countries meet for last time ahead of Paris climate summit