Factcheck: Are climate models ‘wrong’ on rainfall extremes?

Robert McSweeney

04.07.16Robert McSweeney

07.04.2016 | 2:28pmSeveral media outlets are reporting that new research shows climate model projections of rainfall extremes may be “flawed” or “wrong”.

The study, published yesterday in Nature, reconstructed periods of wet and dry extremes for the last 12 centuries. The paper says that large extremes of wet and dry conditions that climate models simulate for the 20th century aren’t found in the reconstruction.

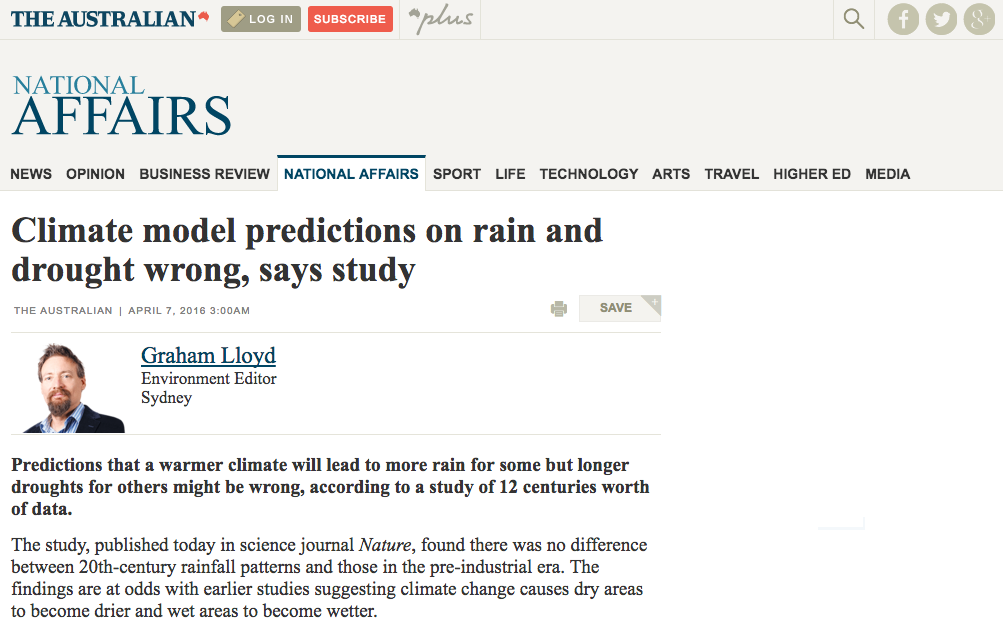

The paper prompted a MailOnline headline of, “Projections of global drought and flood may be flawed”, while the Australian followed suit with, “Climate model projections on rain and drought wrong, study says”. Elsewhere, a brief news story in today’s Times – subsequently bumped from the second edition – claims that “climate scientists have wrongly blamed manmade emissions for droughts and floods”, under the headline “Climate change row”.

But other scientists tell Carbon Brief that the discrepancy between the data reconstruction and model simulations is more likely because the reconstruction underestimates climate extremes, not that models overestimate them.

MailOnline, 6 April 2016.

Proxy records

The focus of the new study is how researchers pieced together a record of extreme wet and dry periods across the northern hemisphere for the past 1,200 years.

To understand how climate changed before anyone was actively taking records, scientists use techniques known collectively as “palaeoclimatology”. These involve looking for climate information in places where it is stored indirectly, such as in tree rings, lake sediments and ice cores.

The researchers used 196 of these “proxy” records to create a “hydroclimate reconstruction” of the northern hemisphere back to the 9th century.

Now, when scientists build climate models, they test them by running them for the past and seeing if the models replicate what actually happened. So, the researchers compared model simulations of past climate against their newly-created reconstruction.

The study finds that the proxy data and model simulations of wet and dry periods match well for most of the past 1,200 years. However, the same isn’t the case for the 20th century, the researchers say.

Lead author Dr Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist, a medieval historian and palaeoclimatologist at Stockholm University, explains to Carbon Brief:

The implication of these findings is that if climate models don’t tally with past climate, this questions how well they can project future climate, Ljungqvist says:

However, Prof Michael Mann, distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University, who wasn’t involved in the study, says the researchers may have got their conclusion the wrong way around. In a post on his Facebook page, Mann writes:

Less variability

Mann suggests that differences between the palaeo record and model simulations are a result of shortcomings in the proxy data, not flaws in climate models, as he explains to Carbon Brief:

Dr Kevin Anchukaitis, associate professor of paleoclimatology at the University of Arizona, who also wasn’t involved in the study, disagrees that proxy records can’t record climate extremes – indeed, it is only through using proxies that scientists know about past extremes, he says.

But where proxies can be used to identify changes over seasons to multiple centuries, they don’t pick up short-term events of days or hours, he tells Carbon Brief:

Prof Steven Sherwood, director of the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales, who also wasn’t involved in the study, makes a similar point:

So, the extremes that climate models simulate for the 20th century are too short-term to be picked up in the proxy data. Responding to the above comments, Ljungqvist agrees that short, recent weather events are not the focus of the study:

For example, for the 20th century, scientists also have the meteorological records they have collected directly. And these show that wet and dry extremes have been intensifying, says Prof Brian Soden, professor of meteorology and physical oceanography at the University of Miami. He tells Carbon Brief:

Big challenge

So, does the study show that climate models are “wrong” on rainfall, as the Australian headline suggests?

In an accompanying News & Views article in Nature, Prof Matthew Kirby, a professor of palaeoclimatology at California State University who wasn’t involved in the study, tackles this exact question:

Sherwood agrees:

Anchukaitis, meanwhile, says he is sceptical about the results because the study is an “apples-to-pears” comparison:

The Australian, 7 April 2016.

Data gathering

Despite reservations about the paper’s conclusions about climate models, there is one element of the study that scientists can be sure about: that gathering more proxy data like this is a good thing.

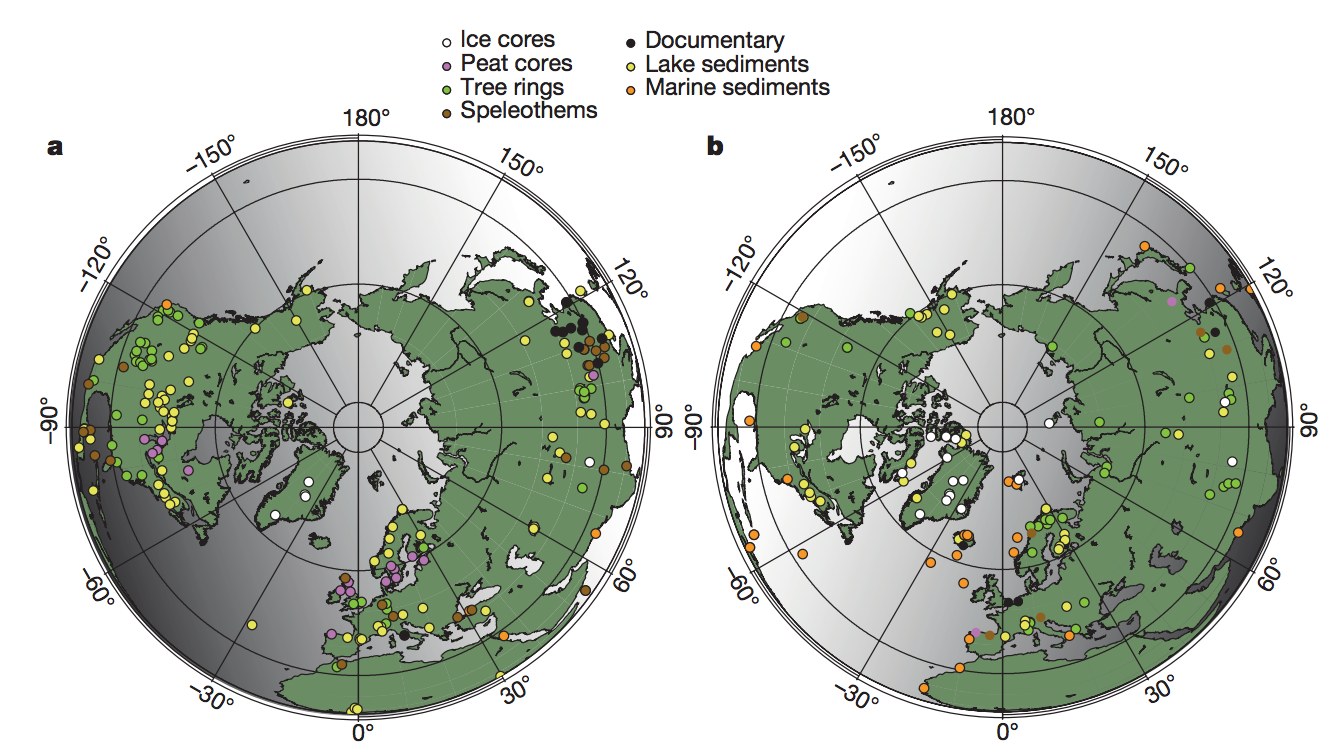

For example, in the maps below from the paper, you can see the sparseness of the proxy records that the researchers had available to create their rainfall (left map) and temperature (right map) records.

Location map of the a) 196 rainfall proxy records and b) 128 temperature records used in the study. All the records cover at least the period 1000-1899. The colour of the dots indicates the type of proxy record (see key). Source: Ljungqvist et al. (2016).

Proxy data covers key regions, such as China, Europe, and much of Central America and North America, Ljungqvist says, but many areas lack data:

Prof Richard Harding from the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology in Wallingford says he hopes the study will encourage more palaeo reconstructions to fill the gaps in the record:

And more comprehensive data allows scientists to refine climate models even further, adds Ljungqvist:

Update 13/04/16: Comments added from Dr Kevin Anchukaitis, and an additional comment from Dr Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist.

Main image: 13 Oct 2015, Barcelona, Spain — After heavy rainfall, the diffuse skyline of Barcelona is emerging in the twilight behind raindrops on a window. — Image by © Erik Tham/Corbis.

Ljungqvist, F. C. et al. (2016) Northern Hemisphere hydroclimatic variability over the past twelve centuries, Nature, doi:10.1038/nature17418.